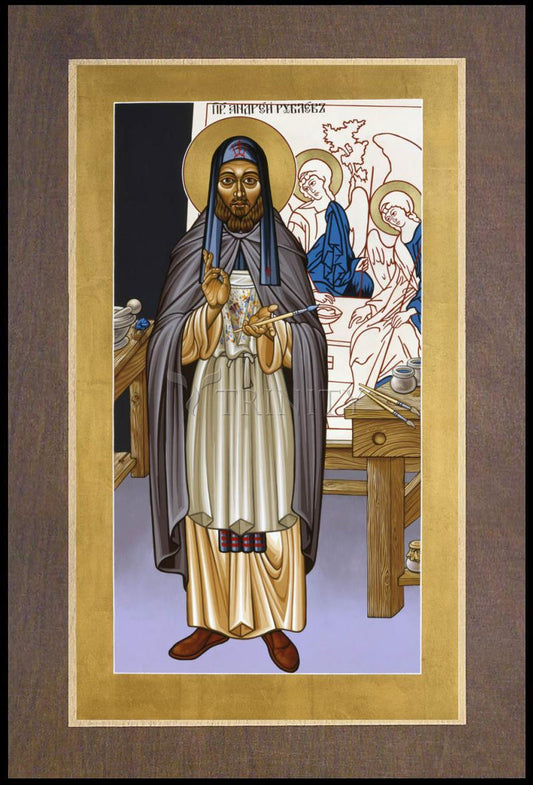

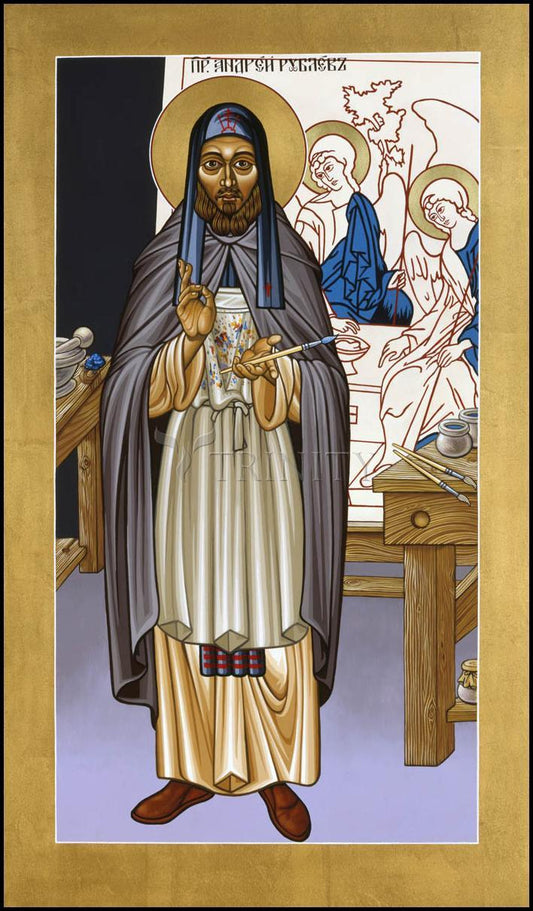

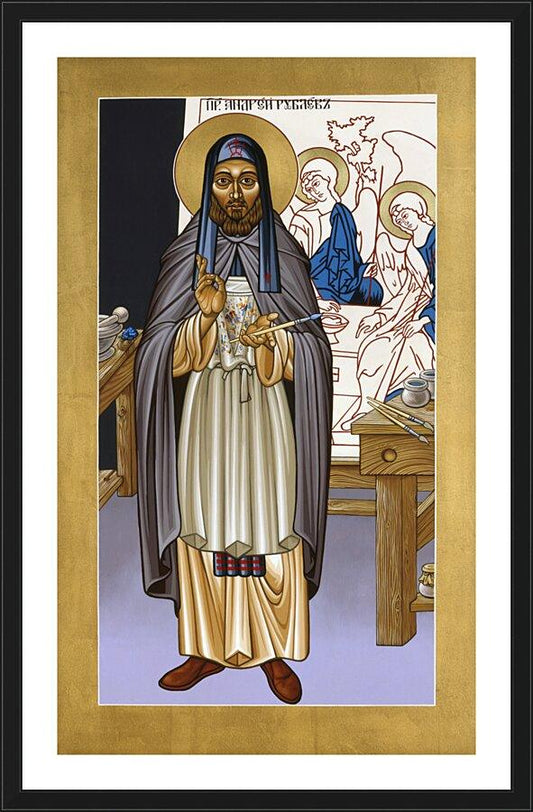

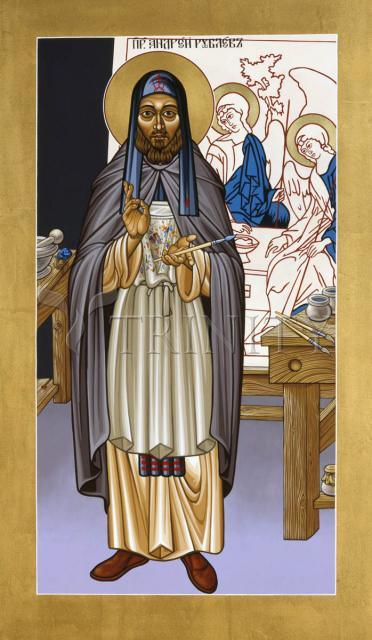

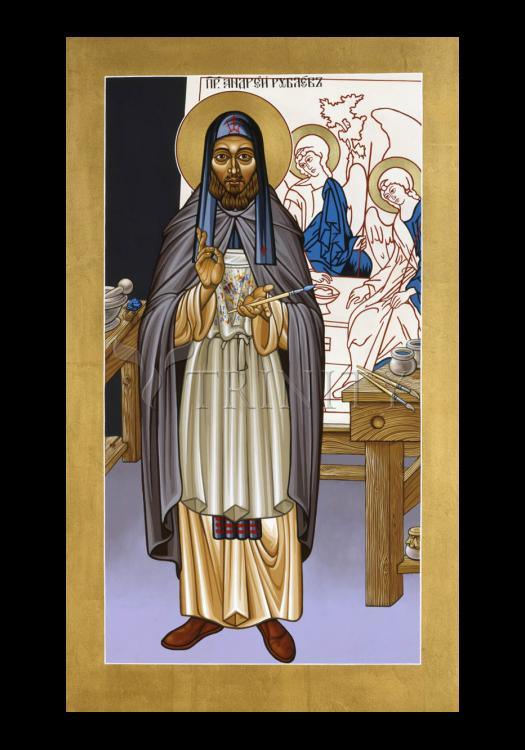

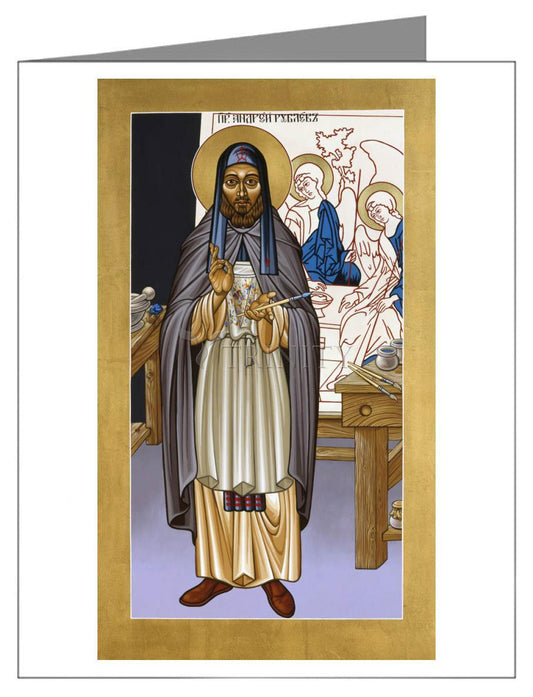

Born in a period of monastic revival, Rublev grew up in the period of increased public trust and support for the Eastern Orthodox Church. Although little is known about his life, sufficient evidence is available to begin to understand his work and the religious convictions that inspired it.

As a monk in the Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery, Rublev was doubtlessly a follower of St. Sergius (1314-1392), who was the founder of the monastery and was in many ways considered the leader of the 14th century spiritual and political revival. Life in the Trinity-St. Sergius monastery emphasized "fraternity, calm, love (toward) God and spiritual self-improvement." In a time of great national division and strife, St. Sergius supported the unification of the quarreling Russian principalities and freedom from the foreign oppression inflicted by the Mongol Yoke.

Many of Rublev's surviving works were created in or near Moscow, and there is evidence to suggest that he received his training in this general area (although not exactly within the city) under the guidance of Prokhor of Gorodets. By 1405 he was collaborating with Theophanes the Greek, the foremost icon painter in Russia at the time, in the decoration of the Annunciation Cathedral in Moscow. This testifies to both his skill and his rising popularity as an icon painter.

Rublev is best known for his masterpiece The Old Testament Trinity. This icon exemplifies the simplicity and the skill of his style, as well as its ability to transcend pictorial constraints with spiritual and religious ideas. Renowned for its lyrical and rhythmic quality, the icon was an instant success and found many imitators. Perhaps Rublev contributed the most to icon painting, however, when he "broke away from the prevailing severity of form, color, and expression" that characterized the developing Russian style of icon painting, especially the work of Theophanes the Greek. Thus did he infuse his work, and that of icons to come, with the gentleness and harmony characteristic for his spiritual outlook.

"Kurt Weitzmann (Knopf)

Andrei Rublev was born circa 1370 (presumably). According to the anonymous author of the The Lives of Russian Saints, a book compiled in the early eighteenth century, Andrei Rublev died on January 29, 1430, and was buried at the Andronikov Monastery in Moscow.

Rublev's name has long become legend. Already in the fifteenth century icons painted by Rublev were considered worth their weight in gold and were much-coveted collectors' items. So great was Rublev's fame, that the Church Council, held in Moscow in 1551, thus prescribed in its statutes the official canon for the correct representation of the Trinity: "...to paint from ancient models, as painted by the Greek painters and as painted by Andrei Rublev..." No wonder numerous works were described to his brush, including such icons that were created by other painters even many years after Rublev's time.

Twentieth century historians of art found that very few of his works ascribed in the chronicles, The Lives of Russian Saints and other sources to Andrei Rublev's brush have survived. Still extant among Rublev's more or less authentic works are individual icons of the festival tier in the iconostasis of the Annunciation Cathedral in Moscow's Kremlin, individual icons and frescoes of the Cathedral of the Assumption of Vladimir and The Old Testament Trinity from the Holy Trinity Cathedral at the St.Sergius Trinity Monastery. Now some of his works can be viewed in both the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow and the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg.

Rublev's name is associated with the history of the Moscow artistic school. Many of his works, just as those of his disciples and followers, originated in Moscow or in towns and monasteries around it. In Moscow, Rublev's clients were Prince Dmitry Donskoy's sons Vasily and Yury, and also the disciples and followers of St. Sergius of Radonezh. The life of St. Sergius, the founder of the Holy Trinity Monastery, was considered an ideal by contemporaries of Rublev. The Monastery of the Holy Trinity was a place where ideas of fraternity, calm, love to god and spiritual self-improvement were expressed. As early as in the fourteenth century the popularity of the Holy Trinity was based not only on its religious content, but also on tragic conditions of Russian political and social life. Those were times of constant feudal strife, which took a toll of thousands of lives and systematically weaken Russian principalities.

The foremost thinkers of the time realized how deadly destructive the feuds were, making Russia an easy prey to enemies. It was clear that the nation has to put an end to internal strife and to throw off the Mongol Yoke. Mingling facts of real life with concepts borrowed from the Gospels and the writings of the Holy Fathers, the medieval mentality embodied these ideas through complex and abstract speculations in the image of the Trinity. Being undivided, the Trinity denounced strife and called for togetherness; being individualized, it condemned oppression and called for liberation.

The fifteenth-century Muscovite, Epiphanius the Wise wrote in the first biography of St. Sergius that the monastery was founded so that "contemplation of the Holy Trinity would conquer the hateful fear of this world's dissensions." St. Sergius of Radonezh, who dedicated the monastery to the Holy Trinity, did not restrict himself to mere prayer in seclusion. St. Sergius had given every possible backing to Prince Dmitry Donskoy's policy towards the unification of the fighting Russian principalities into a single state and towards delivering the Russian people from the hateful Mongol Yoke. His policy became reality following the first significant victory of Russian army in the battle on Kulikovo Field (September, 1380). Because the river Don flows nearby from the Kulikovo Field, the prince Dmitry was titled Donskoy after this battle. Obviously, much in Rublev's beliefs conformed to the beliefs of St. Sergius. This observation leads to an understanding of the painter's philosophy.

In the medieval Russia, all newly-painted icons were coated with a layer of a special drying oil to protect the painting against mechanical damage and impart greater intensity to the colors. Unfortunately, with time oil darkened, thereby darkening the initial colors of icons and eventually turning absolutely black. For this reason, the icon had to be renewed, and the Trinity was painted over with fresh paints within its faintly discernible contours. This procedure was repeated several times. Towards the turn of the twentieth century there remained nothing of Rublev's masterpiece apart from the rapturous recollections of antiquity.

The first attempt to remove later accretions from the fifteenth-century icon was made in 1905. At the end of 1918 restoration work was continued, the surround was removed and it is only since then that the icon's appearance has become close to the original. We say "close to" because in these long five centuries the icon's painting turned out to be damaged: the gold background was lost, the tree was painted anew within the old contours, the top layers of paint were washed off, even the ground was occasionally disturbed and cracks appeared, the outlines of the Angels' heads were partly altered. All this notwithstanding, even in its present state the Trinity remains one of the best extant Russian icons.

The subject of the icon is based on the Biblical story about the visit by three Angels to the Prophet Abraham and his wife Sarah. According to the theological interpretations whose authors associated the Old Testament events with events of the New Testament, these Angels were the three Persons of the Trinity: God the Father, God the Son and the Holy Spirit. Though revealing direct iconographic affinity with this kind of representations, the Trinity as painted by Rublev, has its own features which carry a new quality and a new content. In Rublev's icon we observe for the first time all the three Angels shown equal.

This icon alone conformed to the strict rules of the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity.

Meantime, some historians of art believe that Rublev expressed in the icon the need for and benefit of love, of a union based on the trust of one individual in another. Whereas Rublev's Trinity is void of any noticeable energy of earthly life, of corporeality of forms and external manifestations of love, equally absent from it is that cold soaring of the spirit, so remote from humans. The image determines the subtle struck balance between soul and spirit, the corporeal and the imponderable, endless and immortal sojourn in the heavens. When speaking of Rublev's work, different authors describe the Trinity's Angels as quiet, gentle, anxious, sorrowful, and the mood permeating the icon as detached, meditative, contemplative, intimate.

Depicting the Trinity as an indivisible essence without beginning and without end, infinite and eternal, Rublev chose repetitive light and airy movement as the leitmotif of the composition. The Angels' attitudes and meaningful gestures, their inclinations are amazing in their dissimilarity while being almost identical, so that the icon leaves the clear impression of a seemingly many-voice talk.

It is not fortuitous that we perceive Andrei Rublev's Trinity as the highest achievement of Russian art. Crowning a long artistic career of a single master, it is also an embodiment of the creative thought of several generations. Just as any other medieval artist, Rublev highly valued tradition and collective effort. All the best features of early fifteenth-century Russian culture merged in the Trinity: a form of philosophical generalization, outworldly abstract, but with an amazingly concrete content, a capacity to express through iconographic images the national character, and artistic skills attaining to the pinnacles of world art.