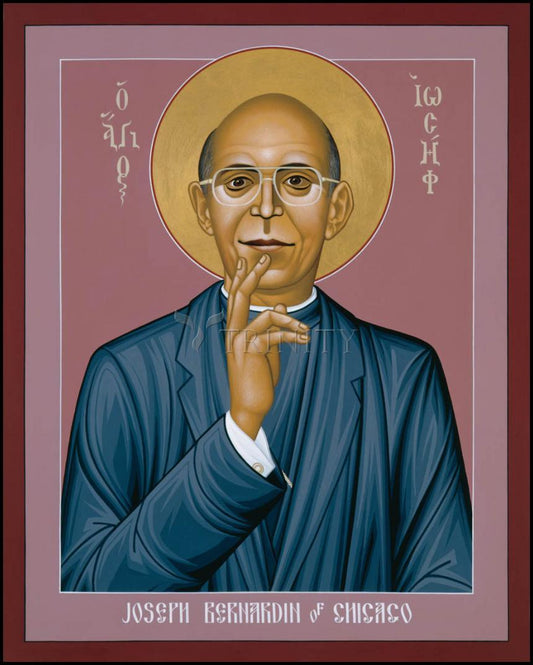

Joseph Louis Bernardin was born April 2, 1928, in Columbia, S.C., to Joseph and Maria Bernardin, recent immigrants from northern Italy's Tonadico di Primiero in the Dolomite mountains.

His stonecutter father died of cancer in 1934, and the cardinal's mother returned to her trade as a seamstress, supporting her son and his younger sister, Elaine.

Ordained a priest in Columbia, in April 1952, Father Bernardin spent two years as an assistant pastor for the Diocese of Charleston before moving into the corridors of power for the next 12 years. Eventually, he ran the diocese after the bishop was transferred and until a new bishop was installed.

Ordained an auxiliary bishop for Atlanta in April 1966, he again filled senior pastoral and administrative posts, including diocesan administrator when Archbishop Paul Hallinan died.

In April 1968, Bishop Bernardin was appointed general secretary -- chief of staff -- to the National Conference of Catholic Bishops (NCCB) and the U.S. Catholic Conference (USCC) in Washington, D.C.

He was installed as archbishop of Cincinnati in December 1972, at St. Peter in Chains Cathedral.

Fellow bishops elected the archbishop to a three-year term as president of the NCCB/USCC in 1974, and they chose him to represent them at worldwide Vatican synods of bishops from 1974 to 1994.

He was installed as archbishop of Chicago in August 1982, and became a cardinal in early 1983.

Cardinal Bernardin chaired the committee that prepared the U.S. bishops' policy statement on peace and war in the early 1980s and the follow-up assessment of the moral status of nuclear deterrence. He also headed the bishops' committees on NCCB/USCC structure and function, marriage and family life, anti-abortion activities, canonical affairs and communication. He served on sacred congregations (Vatican departments) for bishops, evangelization, sacraments and divine worship, on papal commissions on social communications and canon law revision, and on the pope's Council for Promoting Christian Unity. He also was a consultant to the Sacred Congregation for Catholic Education and chairman of the board of the National Catholic Educational Association.

In the 1970s, Archbishop Bernardin was on the President's Advisory Committee for (Vietnamese) Refugees and the President's American Revolution Bicentennial Advisory Council.

Cardinal Bernardin was a founder and vice chairman of the Religious Alliance Against Pornography, and he served on or led numerous boards related to church institutions.

In late 1993, Steven Cook accused Cardinal Bernardin of sodomy when Mr. Cook was an Elder High School student in a pre-seminary program. A year later, Mr. Cook recanted and accepted Cardinal Bernardin's unflinching denial of any wrongdoing.

On June 14, 1995, physicians said that Cardinal Bernardin's pancreas was cancerous and that the disease had spread. Pancreatic cancer treatment began. A cancerous kidney was removed July 12, 1995, during surgery for a benign tumor on his liver.

In mid-1996, pancreatic cancer returned and spread to his liver, and Cardinal Bernardin announced he might have a year to live.

On Sept. 9, President Clinton gave Cardinal Bernardin the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor for individuals' contributions to their communities.

Cardinal Bernardin abandoned chemotherapy in mid-October and handed off daily duties to auxiliary bishops at the end of the month.

To understand the legacy of Cardinal Joseph Louis Bernardin, it is necessary to understand the Roman Catholic Church during the era he helped lead it.

The cardinal was a 34-year-old priest when the church-rattling event known as the Second Vatican Council convened. By the time the council ended more than three years later, the church was changed forever - with reverberations that continue today. An institution that had shunned the modern world now resolved to influence that world. A church hierarchy that had held itself up as the ''one, true'' faith now reached out to other traditions, and to the laypeople in its pews.

And a church that had always presented a unified front was now riven with dissent. Traditionalists thought the changes went too far, while progressives fought for more reform.

Father Bernardin became Bishop Bernardin less than a year after the council ended. And for the rest of his life, the man with an unusual talent for bringing people together worked in a church where polarization threatened to tear it apart.

''Cardinal Bernardin was formed by the council and took seriously Vatican II's emphasis on the rededication of the church to the problems of the world, and to the description of the church itself as the People of God,'' said Scott Appleby, director of the Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism at the University of Notre Dame.

''His leadership style became synonymous with post-Vatican II American Catholicism. It was collaborative, consensus-building, conciliatory and dedicated to moving the Catholic Church into the mainstream of the American public discourse about the common good."

Even critics, who feared that his attempts at consensus-building allowed for too much compromise, acknowledged the legacy he left.

''I wasn't in sympathy with a lot of his substantive programs, but in my view, he was an extraordinarily skillful ecclesiastical figure,'' said James Hitchcock, a professor of history at St. Louis University and a prominent Catholic conservative. ''In the history of the American hierarchy, I can think of very few prelates who shaped the hierarchy and learned to use it as effectively as he did."

POSITIONS OF RESPONSIBILITY

Cardinal Bernardin's resume contained countless impressive titles and positions - archbishop of Cincinnati, archbishop of Chicago, a regular participant in the Vatican synods held every three years in Rome. But it was his work in the National Conference of Catholic Bishops - first as general secretary and later president - that had the greatest influence on the American Catholic Church.

''He, more than anyone else, breathed life into the new institution in the church called the bishops' conference,'' said the Rev. Thomas Reese, a senior fellow at Woodstock Theological Seminary in Washington, D.C. ''He was acknowledged as a leader not only in Chicago, not only in the U.S., but in the world."

The conference was founded in 1968 to give the bishops a greater voice in social issues and public policy matters. He was elected president in 1974, commuting between his office at Eighth and Walnut streets in Cincinnati and Washington, and during his three-year tenure, he met and worked with the future pope.

Conservatives were suspicious of the conference, arguing that it was wrong to establish an American presence separate from Rome.

''The conference was established not in conflict with Rome but certainly as an alternative to Rome, and in my view, the two aren't always compatible,'' Professor Hitchcock said. ''I think Cardinal Bernardin, for better or for worse, deserves credit for putting that machinery together."

EXTENSIVE INFLUENCE

Cardinal Bernardin's work as a national and international church leader reflected his work as a local leader in Cincinnati and Chicago. But those who study the Catholic Church say the cardinal's legacy goes beyond the offices he held. At crucial moments in the history of the American church, observers say, his leadership allowed the accomplishment of the near-impossible.

Take, for instance, the bishops' document on peace and war, crafted in the early 1980s. Then-Archbishop Bernardin headed the committee, whose members ranged from liberal pacifists to conservative hawks. The debate was largely held in hearings and under the glare of television lights - not the normal church procedure on a contentious issue. The process won him a Time magazine cover, as well as some new critics.

''What was unique about (the peace pastoral letter) was the process, and the process reflected the man,'' said the Rev. Richard Marzheuser, dean of the Athenaeum of Ohio/Mount St. Mary Seminary in Mount Washington. ''He pioneered a grass-roots process that involved many levels of the church, and the bishops took that information and made a document out of that. He reversed the process."

The archbishop defended himself at the time against critics who said the bishops were overstepping their bounds.

''It's our responsibility to address the moral dimension of the social issues we face,'' he told Time. ''What we are trying to do is focus on the teaching of the Gospel as we understand it, and to apply that teaching to the various social issues of the day. Our central theme is our respect for God's gift of life, our insistence that the human person has inherent value and dignity."

CONSISTENT ETHIC OF LIFE

Another issue that required careful navigation of the middle ground was Cardinal Bernardin's championing of what is known as ''a consistent ethic of life.'' In the early to mid-1980s, conservatives argued that abortion and euthanasia were the primary issues requiring action, while liberals emphasized poverty and the Cold War.

In a series of speeches, the cardinal argued that the issues were linked - that poverty and abortion were equally important and both required forceful responses.

''His commitment to a consistent ethic of life showed the bishops cared not only about children in the womb, but also children in the street, children in poverty, children in war,'' Father Reese said. ''It said that all life is precious."

Pope John Paul II later explicitly endorsed the consistent ethic of life in papal teachings, said Dennis M. Doyle, an associate professor of religious studies at the University of Dayton. In picking up a thread from both the right and the left, Cardinal Bernardin forced both sides to re-examine their positions.

''Bernardin's role was to point out how concern about all those issues are related. There's tremendous harmony found in why anyone would oppose abortion and euthanasia on one hand, and on the other hand the gap between the rich and the poor, capital punishment, and at the time, the Cold War,'' Professor Doyle said. ''There are all kinds of groups nationally, grass-roots, social-justice groups throughout the U.S. that have found their main inspiration in the consistent life ethic."

COMMON GROUND

Earlier, Cardinal Bernardin launched yet another attempt at drawing people together, the Catholic Common Ground Project. A series of conferences on thorny issues - the role of women, the relationship between church and society, sexual issues - aims to bring the left and right into the same room for dialogue.

The idea brought unusually public criticism from a few fellow cardinals, who feared the impression that Catholic doctrine was subject to compromise. An inaugural event was held.

For observers of the cardinal's career, the proposal is pure Bernardin - and again a response to divisive times.

''This Common Ground project is not an idea that came at the end of his life. He's been a common ground person his entire life,'' Father Marzheuser said. ''Even if it's just pluralism without polarization, you still need someone to be an apostle for the common ground. But in polarized times, common ground becomes all the more important."