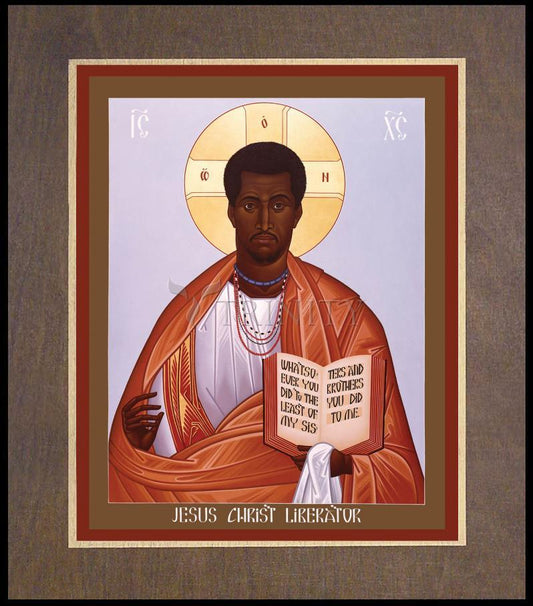

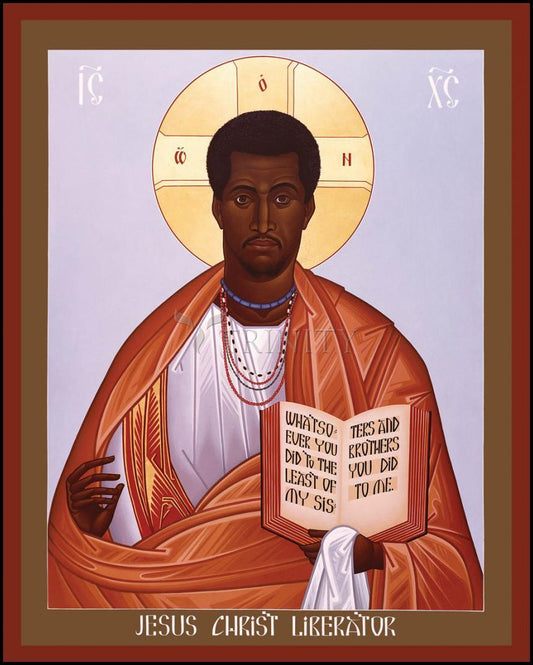

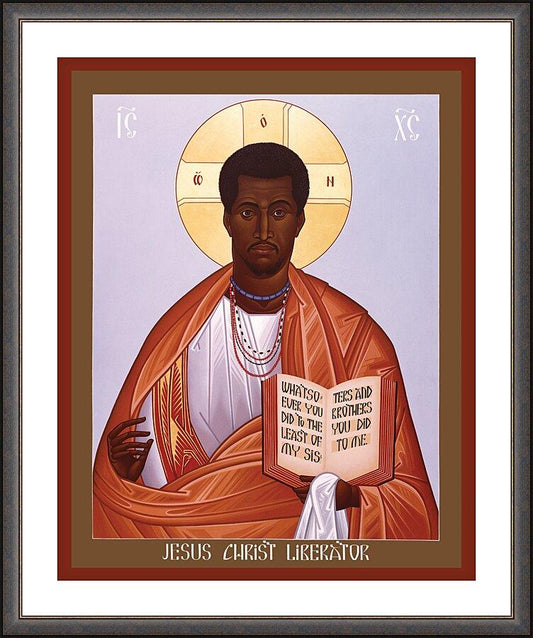

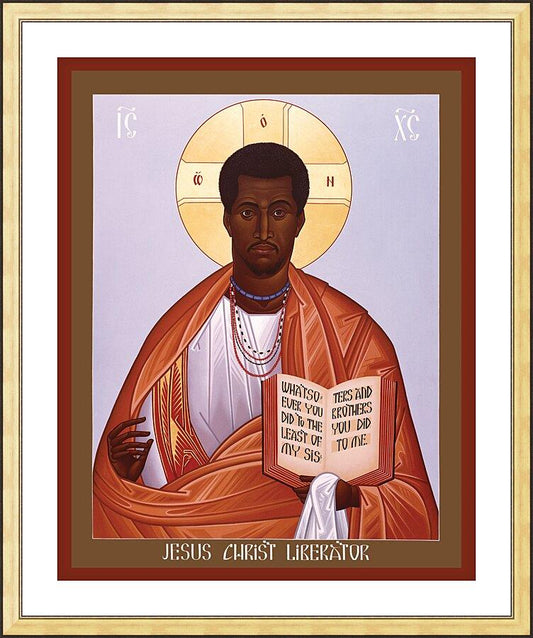

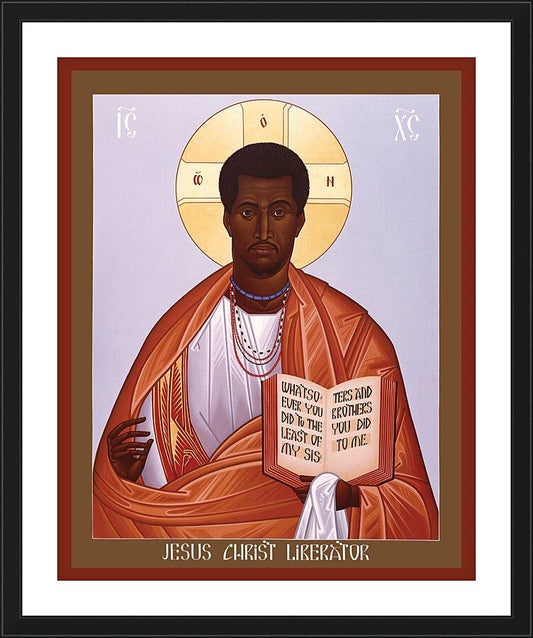

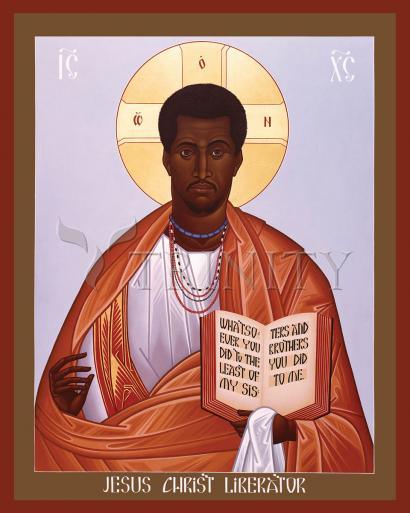

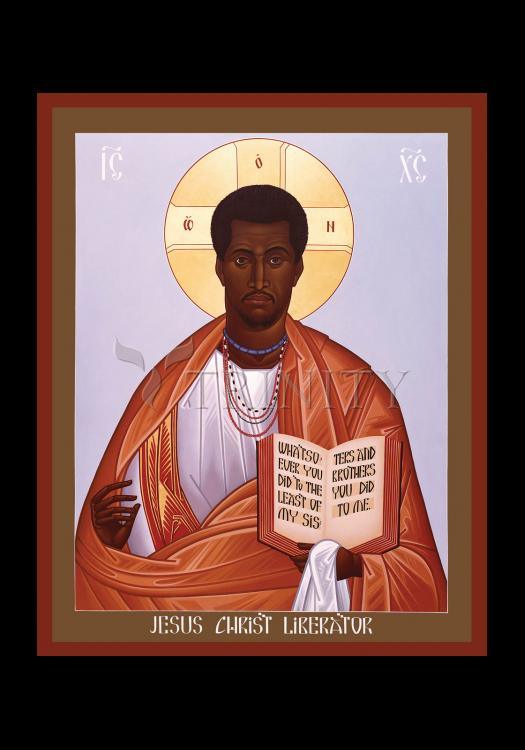

One sign of the vitality and seriousness of Latin American theology of liberation is the interest these theologians have shown not only in the historical Jesus but in Christology as well, and the quality of work they have done. In recent years, several excellent books on Christology have been written by Latin American scholars. Thanks to Orbis Books, they are now available in English. Jesus Christ, Liberator, first published in Brazil in 1972, has just appeared in English translation.

Boff, a Franciscan priest, is an excellent scholar. His mastery of German New Testament research, both Catholic and Protestant, is formidable. He combines with this scholarship his own stance as a man of faith firmly situated in the Latin America of today. For him this means not only a careful understanding of social and political realities but also a commitment to struggle for the transformation of an oppressive and dehumanizing social order. Consequently, he brings to his New Testament work certain "preoccupations that are ours alone," because of which "the facts will be situated within other coordinates and will be projected within an appropriate horizon."

I am a missionary, not a New Testament scholar, and my comments on Boffs work and its significance will be made from that perspective.

With other Latin American theologians, he stresses the historical Jesus over the Christ of faith. Because of the "structural similarity" between the situation in Jesus' day and in Latin America, Jesus' words and actions speak directly to the experience of Christians there. Jesus' critique of an oppressive society, his vision of the Kingdom as the "utopia of a fully reconciled world," the reaction produced by his "liberation praxis" -- all these illumine and inspire the struggle of Christians today. Further, Boff contends that if we follow the life and cause of Jesus in our own lives, then the truth of Jesus surfaces for us.

To me the most interesting part of the book is Chapters 3 through 7 in which Boff presents a portrait of Jesus as seen in the Gospels. What is striking in this portrait is the depth and richness of the humanness of Jesus. In his life, a radical challenge to the established order is combined with a compelling vision of a totally transformed humanity. The man who lives fully for others is a remarkably strong individual "a man of extraordinary good sense, creative imagination and originality," a man with the courage to say "I" over against all authority.

It is hardly surprising that from this portrait the author moves to Christology, in fact, to the inevitability of Christological reflection. Who is this unique person? We can hardly escape the conclusion that "the human being who emerges in and through Jesus is divine." Only God himself could be so human.

Starting with this question, as posed by the life and story of Jesus, Boff explores the historical development of Christology from the earliest responses found in the New Testament until Chalcedon. He spells out and affirms the main lines of the classical dogma. He then proceeds to present what he calls "elements of a Christology in secular language," drawing primarily from Teilhard de Chardin. In doing this he breaks out of the sterile conceptual abstractions in which many of us are imprisoned, and he speaks of Christ in relation to the process of cosmic and historical development. Christ manifests the goal toward which human beings and the cosmos are marching total cosmic-human-divine realization and fullness. Thus, Christ is at the very center of our historical struggles; "the function of Christology is to shape and work out an option in society." (p. 293)

Boff's passionate concern is that we be enabled to speak powerfully about Jesus Christ today, that we name him for our generation. Out of his experience in Brazil, he knows that this calls for something more than repetition or re-interpretation. "In Christology, it is not sufficient to know what others have been." (p 227) Faith in Christ cannot be reduced to archaic formulas. In each generation we must give him names which correspond to our living experience of his inexhaustible reality.

The author realizes that this is not an easy task. "We know in minute detail what others have known in the past... but we are very poorly, informed as to how to carry on the same process." (p 227) In his last three chapters and epilogue (written especially for the English edition), Boff attempts this Christological task. And, in my judgment, he fails.

His failure consists in not taking into account the radical change now occurring in human consciousness and the present and future effects of this change upon our thought. He cannot see how far the crisis of the western cultural tradition has gone, or how dramatically this will affect our reflection about Jesus Christ and what he means for us.

Consequently, what Boff has to say may provide orientation and empowerment for those who still feel at home in the culture we have inherited, it will not be heard by, or make

Jesus Christ compelling for, those who are already living in another reality.

And yet, the Jesus whom Boff portrays throughout his book is one who was and always will be rejected by those who live in the past. His life and work speak most poignantly to those who are open to the in breaking of a new future and yearn most passionately for it.

"Excerpts from "Jesus Christ Liberator: A Critical Christology for Our Time" by Leonardo Boff