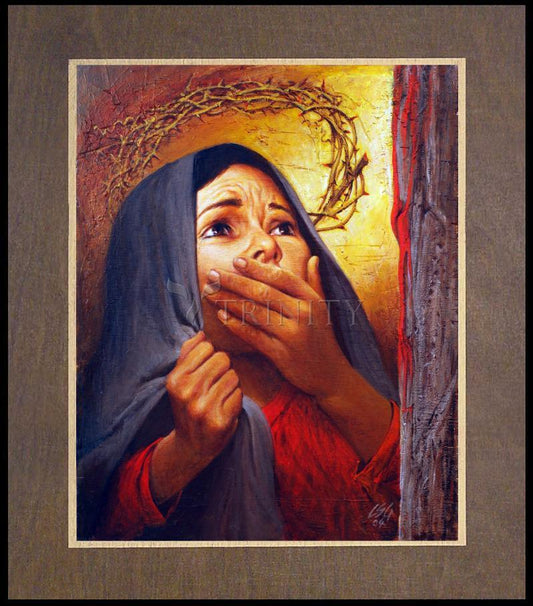

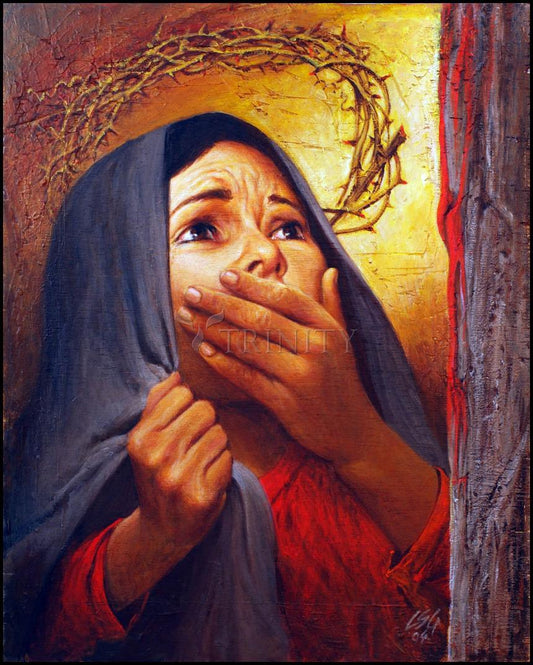

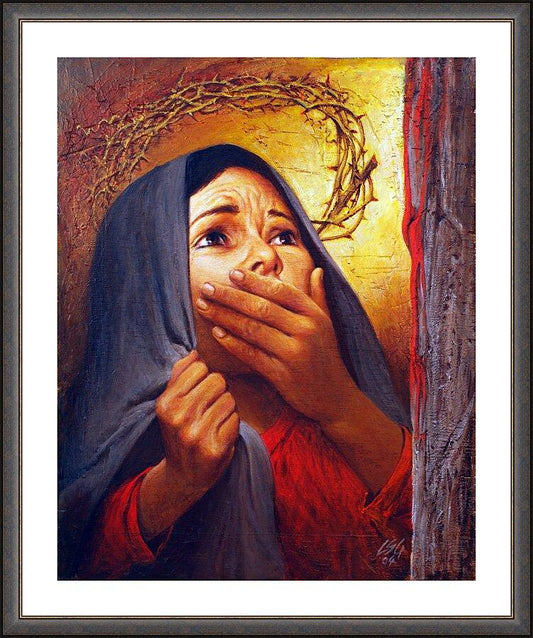

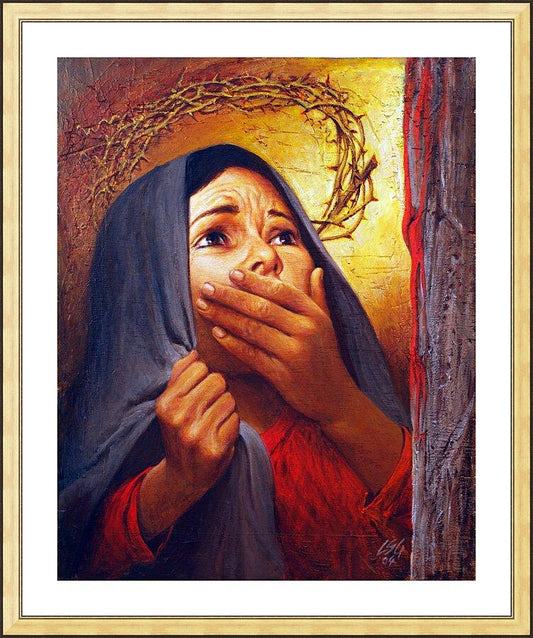

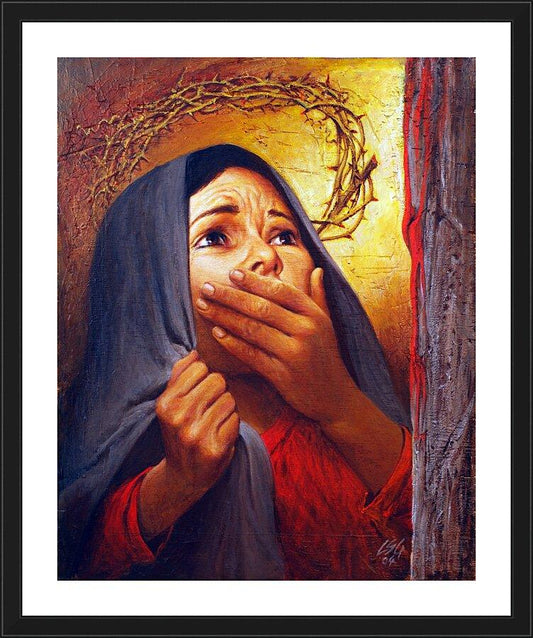

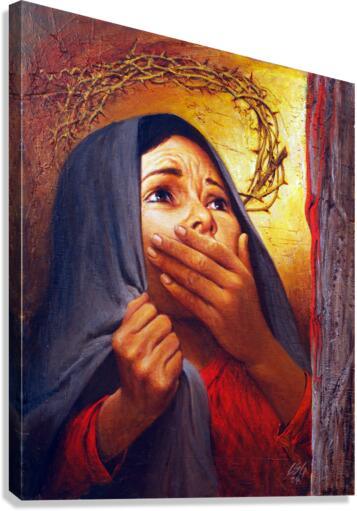

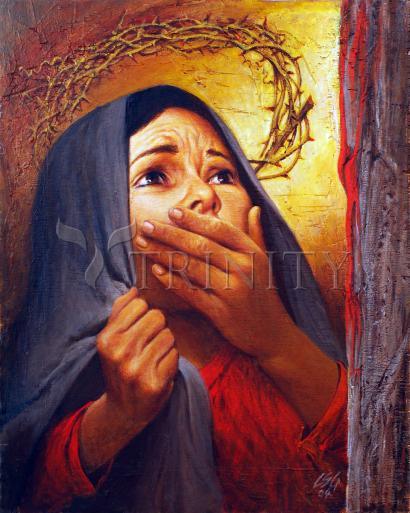

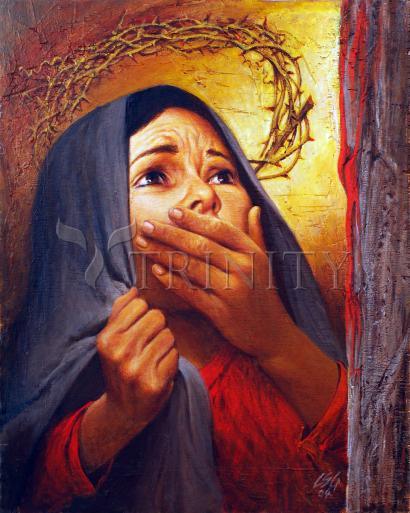

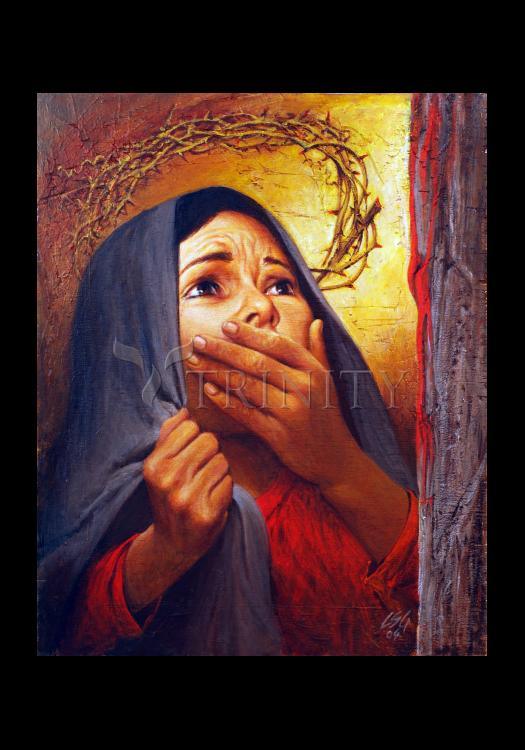

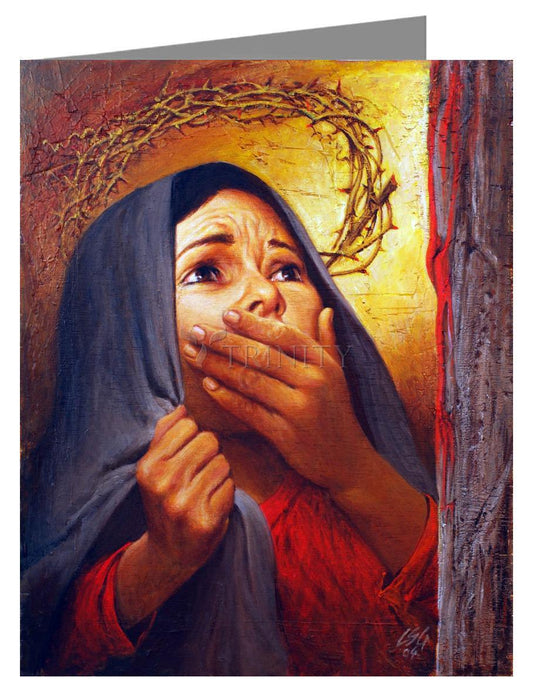

Along with Gabriel's Annunciation to Mary (Luke 1:26-38), her Visitation to Elizabeth (1:39-56), and Jesus' birth and infancy (2:7,16; Matthew 2:11), one other biblical scene depicting the mother of Jesus is especially prominent in the history of Christian art: Jesus' death on the cross (John 19:25-27).

Alone among the evangelists, it is John who informs us that "standing by the cross of Jesus were his mother and his mother's sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene. When Jesus saw his mother and the disciple whom he loved standing nearby, he said to his mother, 'Woman, behold, your son!' Then he said to the disciple, 'Behold, your mother!' And from that hour the disciple took her to his own home."

Tender meditations

Over the centuries this scene of immense tenderness immediately preceding the death of Jesus has inspired, not only many Byzantine ikons, works of statuary beyond count, and numerous paintings in every generation, but also a wealth of hymns penned and sung by Christians in both East and West. The poetry and imagery of these diverse hymns share the common purpose of bringing the Christian imagination into a vivid awareness of the pain and dereliction of Jesus' mother standing by his cross, as he entrusts her to the care of "the disciple whom he loved."

What has prompted Christians to think so long and lovingly on this theme?

The emotional impulse to dwell on the sorrow of Jesus' mother at the foot of the Cross had its root in the very love symbolized by the Cross. Simply put, Jesus died because he loved us. And such sacrificial love elicited a responding love from the believing heart. Christian emotional response to the sufferings of Jesus, then, has traditionally been deep and abiding. We sense this in the devout tenderness of Paul's assertion, "I have been crucified with Christ. It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me. And the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me" (Gal. 2:20). Paul was one of the first of those Christians who, from the very beginning, have demonstrated a sustained, overwhelming disposition to "survey the wondrous Cross where the young Prince of Glory died."

Christians have always known, of course, that the victory of the Cross is inseparable from the Lord's Resurrection. They have never been in doubt that Jesus was "raised for our justification." Yet, their warmest sentiments have traditionally been directed to the harsher fact that He "was delivered up for our offenses" (Romans 4:25). From the beginning, that is to say, they were disposed to dwell in imagination, distress, and deep empathy on the thought of what Jesus endured on their behalf. Even his wounds were treasured, because He "Himself bore our sins in His own body on the tree, that we, having died to sin, might live for righteousness"by whose stripes you were healed"

(1 Peter 2:24)