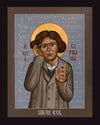

Collection: Pedro Arrupe, SJ

-

Sale

Wood Plaque Premium

Regular price From $99.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$111.06 USDSale price From $99.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wood Plaque

Regular price From $34.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$38.83 USDSale price From $34.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wall Frame Espresso

Regular price From $109.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$122.17 USDSale price From $109.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wall Frame Gold

Regular price From $109.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$122.17 USDSale price From $109.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wall Frame Black

Regular price From $109.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$122.17 USDSale price From $109.95 USDSale -

Sale

Canvas Print

Regular price From $84.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$94.39 USDSale price From $84.95 USDSale -

Sale

Metal Print

Regular price From $94.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$105.50 USDSale price From $94.95 USDSale -

Sale

Acrylic Print

Regular price From $94.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$105.50 USDSale price From $94.95 USDSale -

Sale

Giclée Print

Regular price From $19.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$22.17 USDSale price From $19.95 USDSale -

Custom Text Note Card

Regular price From $300.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per$333.33 USDSale price From $300.00 USDSale

ARTIST: Br. Robert Lentz, OFM

ARTWORK NARRATIVE:

Pedro Arrupe knew conflict. As a young Jesuit, he had to leave his native Spain because of civil war. As a young priest in wartime Japan, he was imprisoned; and he was in Hiroshima when the atomic bomb was dropped. As Jesuit superior general in Rome, he guided the order through the social and religious chaos of the 1960’s and 1970’s.

In times of conflict, people looked to Pedro Arrupe for peace. In Hiroshima, after the atomic blast, while celebrating mass in the Jesuits’ ruined chapel now crammed with the wounded and burnt, he turned at one point to these people, who had no idea what the Eucharist meant, and overwhelmed by the sight he stood as if paralyzed, his arms outstretched. "They were all looking at me," he said, "eyes full of agony and despair as if they were waiting for some consolation to come from the altar." While Jesuit superior general, he knelt before the pope to receive his blessing; photos of this were an image of peaceful fidelity.

Pedro Arrupe’s trust in God never wavered, and he communicated this in his soft, warm smile. This was not the smile of denial but of insight. This smile sprang from a heart that knew God’s love and loved God’s creation. It was the smile of one who could challenge students to be "men and women for others," challenge them in fact to be like himself. The smile, rare in the icon tradition takes on the symbolic power of a material object.

In 1981, Pedro Arrupe suffered a severe stroke, and for the next decade he showed how one can find God in suffering and decline. In 1983, he ended his last public message, "I am full of hope!" Someone had to read the message for him, but Pedro Arrupe was smiling.

- Lentz collection:

-

Ecumenical Icons

Pedro Arrupe, SJ, was the 28th Superior General of the Society of Jesus, leading the Society in the realities of serving the Church and people in the post-Vatican II world. Arrupe was a man of great spiritual depth who was committed to justice.

Early Years

Arrupe was born in the Basque region of Spain in 1907. After some years of medical training, Arrupe entered the Jesuits in 1927. In 1932, the Republican government in Spain expelled the Jesuits from the country. Arrupe continued his studies in Belgium, Holland, and the United States. After being ordained, Fr. Arrupe was sent to Japan in 1938. He hoped to work there as a missionary for the rest of his life.

Arrest and Imprisonment

After the December 7, 1941, bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Japanese security forces arrested Arrupe on suspicion of espionage. He was kept in solitary confinement. Arrupe described the privation and uncertainty he suffered as he waited for the disposition of his case. He missed celebrating the Eucharist most of all. In the midst of his suffering, Arrupe experienced a special moment of grace. On Christmas night, 1941, Arrupe heard a group of people gathering outside his cell door. He could not see them and wondered if the time of his execution had come.

Suddenly, above the murmur that was reaching me, there arose a soft, sweet, consoling Christmas carol, one of the songs which I had myself taught to my Christians. I was unable to contain myself. I burst into tears. They were my Christians who, heedless of the danger of being themselves imprisoned, had come to console me. (Pedro Arrupe: Essential Writings, Kevin Burke, Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books 2004, p. 57)

After the few minutes of song, Arrupe reflected in the presence of Jesus, who would soon descend onto the altar during the Christmas celebration: “I felt that he also descended into my heart, and that night I made the best spiritual communion of all my life." (Ibid. p. 58)

When the security forces came after 33 days to release him from captivity, Arrupe was convinced that they were coming to execute him. The experience of captivity filled him with a deep inner calm founded on a radical trust in God.

Hiroshima, August 6, 1945

Arrupe moved to Nagatsuka, on the outskirts of Hiroshima, where he resumed his duties as the master of novices for the Japanese mission. On August 6, 1945, he heard the sirens wail as a single American B-29 bomber flew over the city. He did not think much of it and expected to hear the all-clear siren soon. Instead he heard an enormous explosion and felt the concussion that blew in the doors and windows of his residence.

Moving outside Arrupe and his colleagues saw the first of the 200,000 casualties of the atomic bomb. Walking up the hill they saw the city of Hiroshima turning into a lake of fire.

Ministering to the Wounded

Arrupe decided to use his medical training to help whomever he could. He and his colleagues were able to give aide to 150 victims. Knowing nothing of the dangers of atomic radiation, they were perplexed and distressed at the many deaths of people who seemed to have no external injuries. Arrupe and his fellow Jesuits had only the most basic food and medical supplies and had to care for people without anesthetics or modern drugs. Nevertheless, of the 150 people whom they were able to take in, only one boy died from the effects of his injuries.

Discovering the Heart of the Poor

When visiting a Jesuit province in Latin America, Pedro Arrupe celebrated the Mass in a suburban slum, the poorest in the region. Arrupe was moved by the attentiveness and respect with which the people celebrated the Mass. His hands trembled as he distributed communion and watched the tears fall from the faces of the communicants.

Afterwards, one especially large man invited Arrupe to his home. The man's home was a half-falling shack. The man seated him in a rickety chair and invited Fr. Arrupe to observe the setting sun with him. After the sun went down, the man explained that he was so grateful for what Arrupe had brought to the community. The man wanted to share the only gift he had, the opportunity to share in the beautiful setting sun.

Arrupe reflected, “He gave me his hand. As I was leaving, I thought: "˜I have met very few hearts that are so kind.'"

Superior General of the Jesuits

Pedro Arrupe was serving as the Superior of the Jesuits' Japanese Province when he was elected Superior General of the Society of Jesus in 1965. He held the position until 1983.

As the 28th Superior, or “Father General," it was Arrupe's task to guide the community through the changes following Vatican II. He was most concerned that the Jesuits make a commitment to addressing the needs of the poor. His work resulted in the decree from the 32nd General Congregation, Our Mission Today: The Service of Faith and the Promotion of Justice, passed in 1975. This led the Jesuits, especially in Latin America, to work in practical ways with the poor. In spite of threats against their lives—threats that led to the murder of six priests in El Salvador in 1989—the Jesuits continued their justice work with the poor, with Arrupe's support.

Arrupe's belief in justice informed his understanding of the goal of Jesuit education. He said:

Today our prime educational objective must be to form men-and-women-for-others; men and women who will live not for themselves but for God and his Christ—for the God-human who lived and died for all the world; men and women who cannot even conceive of love of God which does not include love for the least of their neighbors; men and women completely convinced that love of God which does not issue in justice for others is a farce.

Additional Items Our Customers Like

-

Eagle and Blind Elder (by Fr. Bob Gilroy, SJ)

-

Eagle Eye (by Fr. Bob Gilroy, SJ)

-

Eagle Feather (by Fr. Bob Gilroy, SJ)

-

Eagle Flying in Freedom (by Fr. Bob Gilroy, SJ)

-

Eagle Hovers Over Ruins (by Fr. Bob Gilroy, SJ)

-

Simone Weil (by Br. Robert Lentz, OFM)

-

Seraphim Rose of Platina (by Br. Robert Lentz, OFM)

-

Syro-Phoenician Woman (by Br. Robert Lentz, OFM)

-

Sweetest Gift, A Mother's Smile (by Dan Paulos)

-

Sun of Justice (by Julie Lonneman)

-

Sts. Mary, Ann, Kateri - Holy Women Pray for Us (by Br. Mickey McGrath, OSFS)