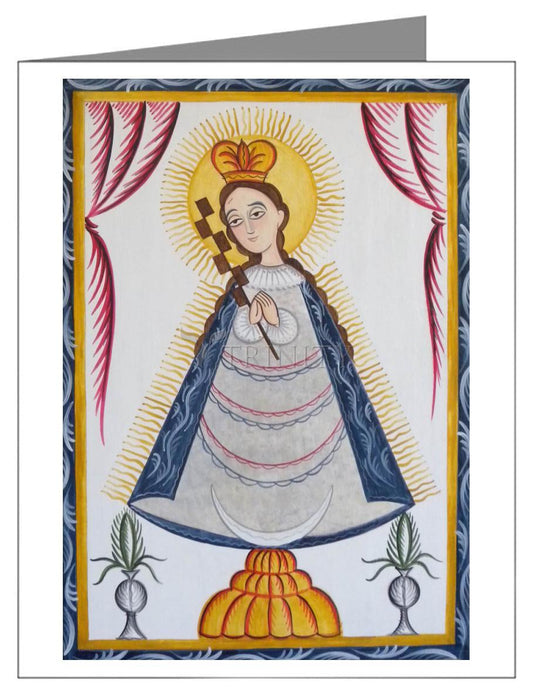

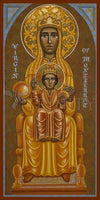

"Nuestra Señora de la Macana" or "Our Lady of the War Club"

As the story goes, in 1598 the Oñate colony brought with them to New Mexico a religious statue of Our Lady of the Toledo Sacristy, which later transformed into "Nuestra Señora de la Macana" through a miracle. The apparition occurred in the early 1670s to the 10-year-old gravely ill, paralyzed daughter of the Spanish colonial Gov. Juan de Durán de Miranda (1671-1675). The statue told the child the province would be destroyed in six years by the Pueblo Indians.

As the statue predicted, the revolt occurred. During the battle, a warrior hit the statue in the head with a sharp macana (Aztec or Nahuatl for a double-sided obsidian war club). Miraculously, only a small scar appeared on the back of the figure's head. Fray Buenaventura de los Carros carried the statue back to Mexico City, where her name was changed. He placed the sculpture in the Convento Grande de Francisco, where it remains today. The young girl lived and returned to Mexico City with the survivors of the Pueblo Revolt.

There are only four known paintings dating to the 18th century that tell the story of this phenomenon, Diaz said. Each tells the story of the Pueblo Revolt. They are the only known visual interpretations of the battle that were created close to the time of the event, most likely by either a witness or someone who was told about the revolt.

Franciscan priest, historian and author Fray Angelico Chavez wrote about the image in the "New Mexico Historical Review" in 1959:

"A most colorful and intriguing tidbit of New Mexican history is the image of NuestraSeñora de la Macana " with its own peculiar story. For this story is a most curious mixture of legend and history. Although both the statue and the story are intimately connected with seventeenth-century New Mexico, particularly with the great Indian Rebellion of 1680, neither was remembered by New Mexicans since those eventful times."