Apache Religion

Apachean religious stories relate two culture heroes (one of the Sun/fire:"Killer-Of-Enemies/Monster Slayer", and one of Water/Moon/thunder: "Child-Of-The-Water/Born For Water") that destroy a number of creatures which are harmful to humankind.

Another story is of a hidden ball game, where good and evil animals decide whether or not the world should be forever dark. Coyote, the trickster, is an important being that often has inappropriate behavior (such as marrying his own daughter, etc.) in which he overturns social convention. The Navajo, Western Apache, Jicarilla, and Lipan have an emergence or Creation Story, while this is lacking in the Chiricahua and Mescalero.

Most Southern Athabascan "gods" are personified natural forces that run through the universe. They may be used for human purposes through ritual ceremonies. The following is a formulation by the anthropologist Keith Basso of the Western Apache's concept of diyÃ':

The term diyÃ' refers to one or all of a set of abstract and invisible forces which are said to derive from certain classes of animals, plants, minerals, meteorological phenomena, and mythological figures within the Western Apache universe. Any of the various powers may be acquired by man and, if properly handled, used for a variety of purposes.

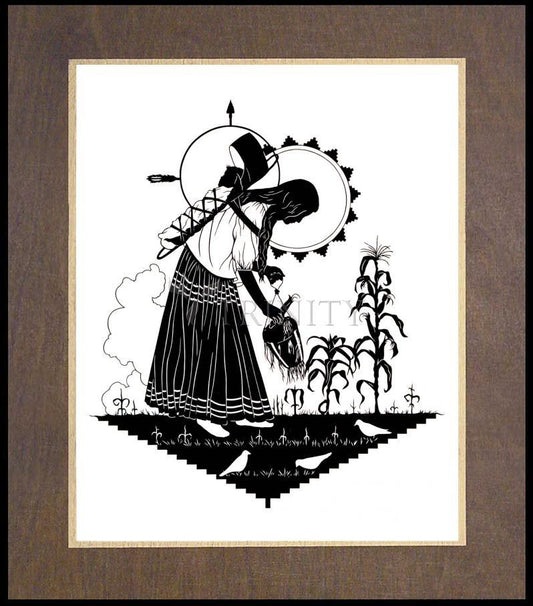

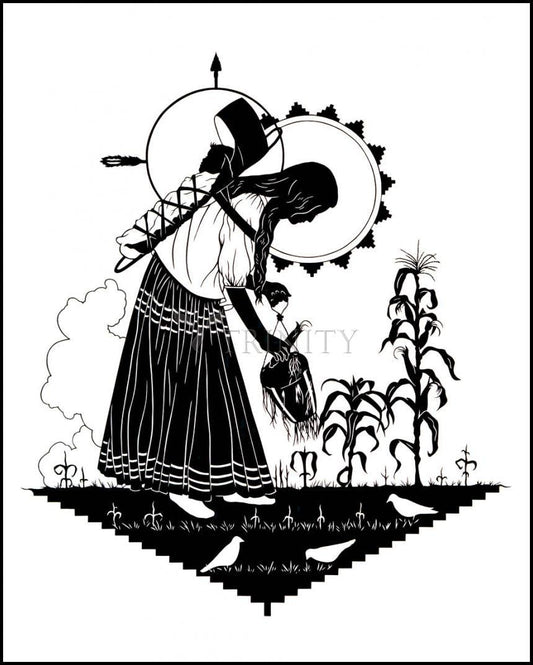

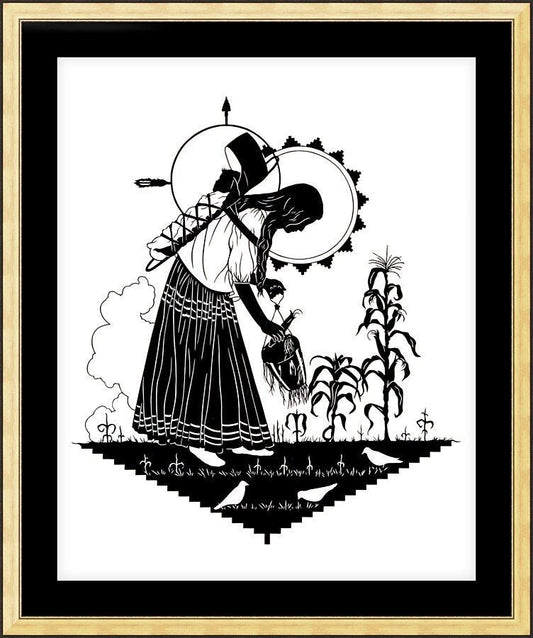

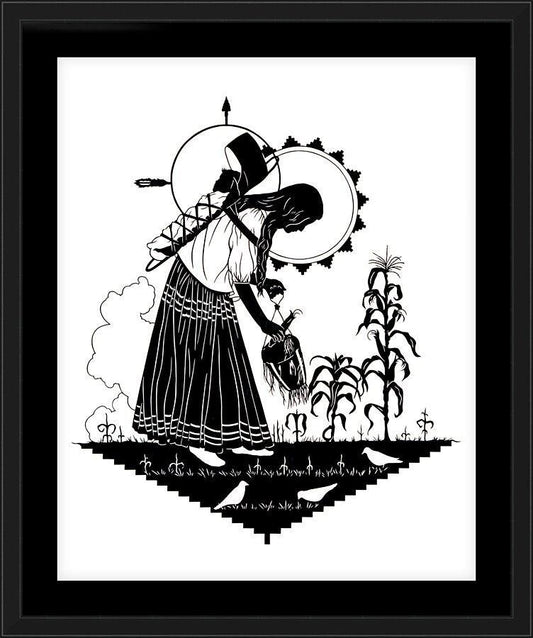

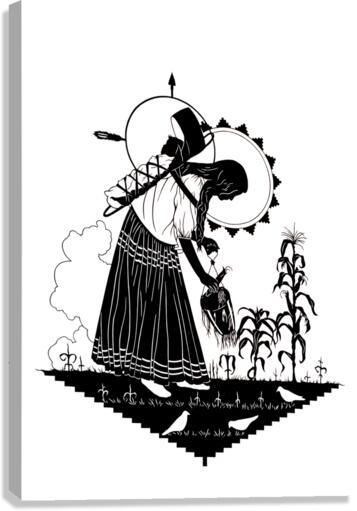

Medicine men (shamans) learn the ceremonies, which can also be acquired by direct revelation to the individual (see also mysticism). Different Apachean cultures had different views of ceremonial practice. Most Chiricahua and Mescalero ceremonies were learned through the transmission of personal religious visions, while the Jicarilla and Western Apache used standardized rituals as the more central ceremonial practice. Important standardized ceremonies include the puberty ceremony (Sunrise Dance) of young women, Navajo chants, Jicarilla "long-life" ceremonies, and Plains Apache "sacred-bundle" ceremonies.

Certain animals are considered spiritually evil and prone to cause sickness to humans: owls, snakes, bears, and coyotes.

Many Apachean ceremonies use masked representations of religious spirits. Sandpainting is an important ceremony in the Navajo, Western Apache, and Jicarilla traditions, in which shamans create temporary, sacred art from colored sands. Anthropologists believe the use of masks and sandpainting are examples of cultural diffusion from neighboring Pueblo cultures.

The Apaches participate in many spiritual dances, including the rain dance, dances for the crop and harvest, and a spirit dance. These dances were mostly for influencing the weather and enriching their food resources.