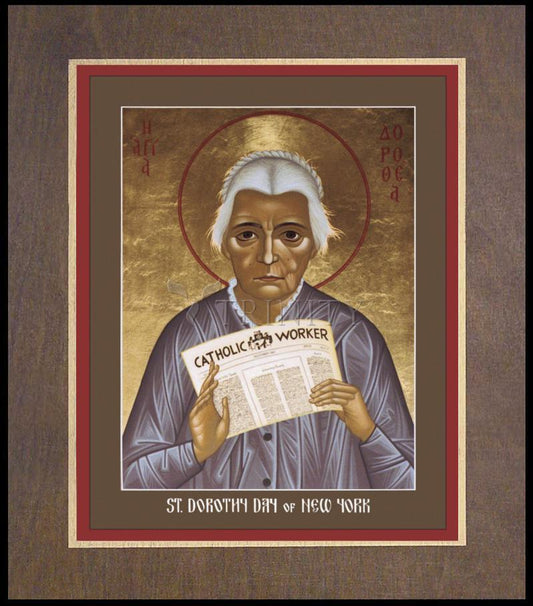

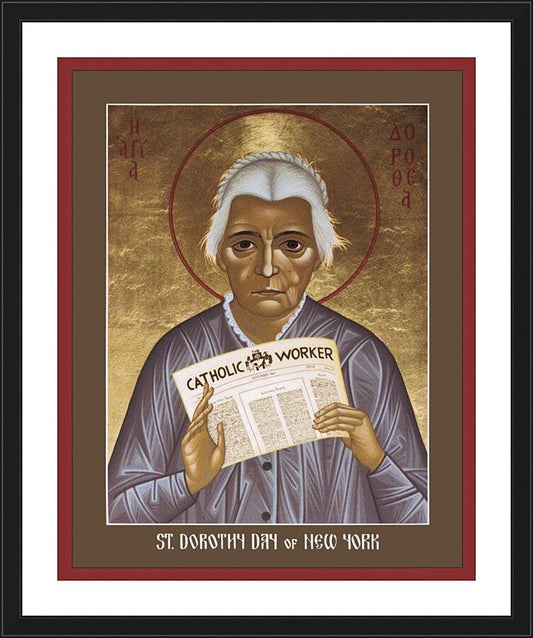

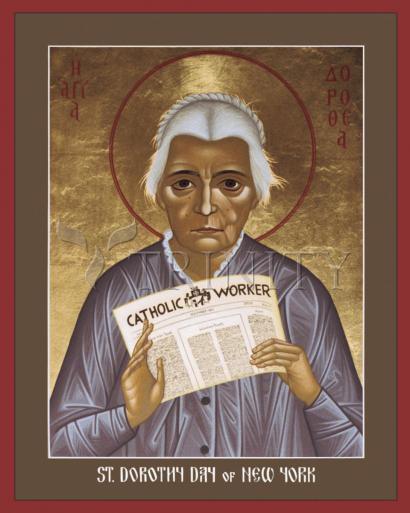

At their 2012 annual meeting, the Catholic bishops of the United States unanimously recommended the canonization of Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker movement. By then the Vatican had already given her the title "Servant of God," the first step in formally recognizing Dorothy Day as a saint. On Ash Wednesday, 2013, preaching in Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome, Pope Benedict XVI spoke of Dorothy Day as a model of conversion.

While awareness of her remarkable life has been growing steadily, she is at present still not widely known. Who was Dorothy Day? Why do so many people regard her as a model of sanctity for the modern world?

She was born into a journalist's family in Brooklyn, New York, on November 8, 1897. After surviving the San Francisco earthquake in 1906, the Day family moved into a tenement flat on Chicago's South Side. It was a big step down in the world, made necessary because John Day was out of work. Day's understanding of the shame people feel when they fail in their efforts dated from this time.

Her father was passionately anti-Catholic, but in Chicago Day began to form positive impressions of Catholicism. Later in life she would recall her discovery of a friend's mother, a devout Catholic, praying at the side of her bed. Without embarrassment, she looked up at Day, told her where to find her daughter, and returned to her prayers. "I felt a burst of love toward her that I have never forgotten," Day recalled.

When John Day was appointed sports editor of a Chicago newspaper, the Day family moved into a comfortable house on the North Side. Here Dorothy began to read books that stirred her conscience. A novel by Upton Sinclair, The Jungle, inspired Day to take long walks in poor neighborhoods on Chicago's South Side, the area where much of Sinclair's novel was set. These long walks were the start of a life-long attraction to areas many people avoid.

Day had a gift for finding beauty in the midst of urban desolation. Drab streets were transformed by pungent odors: geranium and tomato plants, garlic, olive oil, roasting coffee, bread and rolls in bakery ovens. "Here," she said, "was enough beauty to satisfy me."

Day won a scholarship that brought her to the University of Illinois campus at Urbana in the fall of 1914, but she was a reluctant scholar. Her reading drew her in a radical social direction. She avoided campus social life and insisted on supporting herself rather than living on money from her father.

Dropping out of college two years later, she moved to New York where she found a job reporting for The Call, the city's one socialist daily; she covered rallies and demonstrations and interviewed people ranging from butlers to revolutionaries.

She next worked for The Masses, a magazine that opposed American involvement in the European war. In September, the Post Office rescinded the magazine's mailing permit. Federal officers seized back issues, manuscripts, subscriber lists and correspondence. Five editors were charged with sedition. Day, the newest member of the staff, was able to get out the journal's final issue.

Day's conviction that the social order was unjust changed in no substantial way from her adolescence until her death, though she never identified herself with any political party.

In November 1917 Day went to prison for being one of forty women arrested in front of the White House for protesting women's exclusion from the electorate. Arriving at a rural workhouse, the women were roughly handled. The women responded with a hunger strike. Finally they were freed by presidential order.

Returning to New York, Day felt that journalism was a meager response to a world at war. In the spring of 1918, she signed up for a nurses' training program in Brooklyn.

Her religious development was a gradual process. As a child she had attended services at an Episcopal Church in Chicago and been baptized. As a young journalist in New York, she would sometimes make late-at-night visits to St. Joseph's Catholic Church on Sixth Avenue. The Catholic climate of worship appealed to her. While she knew little about Catholic belief, Catholic spiritual discipline fascinated her. She saw the Catholic Church as "the church of the immigrants, the church of the poor."

In 1922, in Chicago working as a reporter, she roomed with three young women who went to Mass every Sunday and holy day and set aside time each day for prayer. It was clear to her that "worship, adoration, thanksgiving, supplication ... were the noblest acts of which we are capable in this life."

Her next job was with a newspaper in New Orleans. Living near St. Louis Cathedral, Day often attended evening Benediction services.

Back in New York in 1924, Day bought a beach cottage in the New York borough of Staten Island using money from the sale of movie rights for The Eleventh Virgin, an autobiographical novel she had written. She also began a four-year common-law marriage with Forster Batterham, a botanist she had met through friends in Manhattan. Batterham was an anarchist who opposed both marriage and religion. In a world of such cruelty, he found it impossible to believe in a God. By this time Day's belief in God was unshakable. It grieved her that Batterham didn't sense God's presence within the natural world. "How can there be no God," she asked, "when there are all these beautiful things?" Batterham's irritation with her "absorption in the supernatural" often led them to quarrel.

What transformed everything for Dorothy was discovering she was pregnant. She had been pregnant once before, years earlier, as the result of a love affair with a journalist. This resulted in the great tragedy of her life, an abortion. The affair's awful aftermath, Day concluded in the years following, had left her barren. "For a long time I had thought I could not bear a child, and the longing in my heart for a baby had been growing," she confided in her autobiography, The Long Loneliness. "My home, I felt, was not a home without one."

Her pregnancy with Batterham seemed to Day nothing less than a miracle. Batterham, however, did not rejoice. He didn't believe in bringing children into such a violent world.

On March 3, 1926, Tamar Theresa Day was born. Day could think of nothing better to do with the gratitude that overwhelmed her than arrange Tamar's baptism in the Catholic Church. "I did not want my child to flounder as I had often floundered. I wanted to believe, and I wanted my child to believe, and if belonging to a Church would give her so inestimable a grace as faith in God, and the companionable love of the Saints, then the thing to do was to have her baptized a Catholic."

Following Tamar's baptism, there was a permanent break with Batterham, a heart-breaking event for Day. On December 28, she was received into the Catholic Church. A period commenced in her life as she tried to find a way to bring together her religious faith and her radical social values.

In the winter of 1932 Day travelled to Washington, D.C., to report for two Catholic journals, Commonweal and America, on a radical protest called the Hunger March. Day watched the protesters parade down the streets of Washington carrying signs calling for jobs, unemployment insurance, old age pensions, relief for mothers and children, health care and housing. What kept Day in the sidelines was that she was a Catholic and the march had been organized by Communists, a party at war with not only capitalism but religion.

It was December 8, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. After witnessing the march, Day went to the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception where she expressed her torment in prayer: "I offered up a special prayer, a prayer which came with tears and anguish, that some way would open up for me to use what talents I possessed for my fellow workers, for the poor."

Her prayer was quickly answered. The next day, back at her apartment in New York, Day met Peter Maurin, a French immigrant 20 years her senior, who was to change her life.

Maurin, a former Christian Brother, had left France for Canada in 1908 and later made his way to the United States. When he met Day, he was a handyman at a Catholic boys' camp in upstate New York, receiving meals, use of the chaplain's library, living space in the barn and occasional pocket money.

During his years of wandering, Maurin had come to a Franciscan attitude, embracing poverty as a vocation. His celibate, unencumbered life offered time for study and prayer, out of which a vision had taken form of a social order instilled with basic values of the Gospel "in which it would be easier for men to be good." A born teacher, he found willing listeners, among them George Shuster, editor of Commonweal magazine, who gave him Day's address.

As remarkable as the providence of their meeting was Day's willingness to listen. It seemed to her he was an answer to her prayers, someone who could help her discover what she was supposed to do.

What Day should do, Maurin said, was start a newspaper to publicize Catholic social teaching and promote steps to bring about the peaceful transformation of society. Day readily embraced the idea. If family past, work experience and religious faith had prepared her for anything, it was this.

Day found that the Paulist Press was willing to print 2,500 copies of an eight-page tabloid paper for $57. Her kitchen was the new paper's editorial office. She decided to sell the paper for a penny a copy, "so cheap that anyone could afford to buy it."

On May 1, the first copies of The Catholic Worker were handed out on Union Square.

Few publishing ventures meet with such immediate success. By December, 100,000 copies were being printed each month. Readers found a unique voice in The Catholic Worker. It expressed dissatisfaction with the social order and took the side of labor unions, but its vision of the ideal future challenged both urbanization and industrialism. It wasn't only radical but religious. The paper didn't merely complain but called on its readers to make personal responses.

For the first half year The Catholic Worker was only a newspaper, but as winter approached, homeless people began to knock on the door. Maurin's essays in the paper were calling for renewal of the ancient Christian practice of hospitality to those who were homeless. In this way followers of Christ could respond to Jesus' words: "I was a stranger and you took me in." Maurin opposed the idea that Christians should take care only of their friends and leave care of strangers to impersonal charitable agencies. Every home should have its "Christ Room" and every parish a house of hospitality ready to receive the "ambassadors of God."

Surrounded by people in need and attracting volunteers excited about ideas they discovered in The Catholic Worker, it was inevitable that the editors would soon be given the chance to put their principles into practice. Day's apartment was the seed of many houses of hospitality to come.

By the wintertime, an apartment was rented with space for ten women, soon after a place for men. Next came a house in Greenwich Village. In 1936 the community moved into two buildings in Chinatown, but no enlargement could possibly find room for all those in need. Mainly they were men, Day wrote, "grey men, the color of lifeless trees and bushes and winter soil, who had in them as yet none of the green of hope, the rising sap of faith."

Many of the down-and-out guests were surprised that, in contrast with most charitable centers, no one at the Catholic Worker set about reforming them. A crucifix on the wall was the only unmistakable evidence of the faith of those welcoming them. The staff received not salary, only food, board and occasional pocket money.

The Catholic Worker became a national movement. By 1936 there were thirty-three Catholic Worker houses spread across the country. Due to the Great Depression, there were plenty of people needing them.

The Catholic Worker attitude toward those who were welcomed wasn't always appreciated. These weren't the "deserving poor," it was sometimes objected, but drunkards and good-for-nothings. A visiting social worker asked Day how long the "clients" were permitted to stay. "We let them stay forever," Day answered.. "They live with us, they die with us, and we give them a Christian burial. We pray for them after they are dead. Once they are taken in, they become members of the family. Or rather they always were members of the family. They are our brothers and sisters in Christ."

Some justified their objections with biblical quotations. Didn't Jesus say that the poor would be with us always? "Yes," Day once replied, "but we are not content that there should be so many of them. The class structure is our making and by our consent, not God's, and we must do what we can to change it. We are urging revolutionary change."

The Catholic Worker has also experimented with farming communes. In 1935, a house with a garden was rented on Staten Island. Soon after came Maryfarm in Easton, Pennsylvania, a property finally given up because of strife within the community. Another farm was purchased in upstate New York near Newburgh. Called the Maryfarm Retreat House, it was destined for a longer life. Later came the Peter Maurin Farm on Staten Island, which later moved to Tivoli and then to Marlborough, both in the Hudson Valley. Day came to see that the vocation of the Catholic Worker was not so much to found model agricultural communities, though several have been productive and long-lasting, as rural houses of hospitality.

What got Day into the most trouble was pacifism. A nonviolent way of life, as she saw it, was at the heart of the Gospel. She took as seriously as the early Church the command of Jesus to Saint Peter: "Put away your sword, for whoever lives by the sword shall perish by the sword."

For many centuries the Catholic Church had accommodated itself to war. Popes had blessed armies and preached Crusades. In the thirteenth century Saint Francis of Assisi had revived the pacifist way, but by the twentieth century, it was unknown for Catholics to take such a position.

The Catholic Worker's first expression of pacifism, published in 1935, was a dialogue between a patriot and Christ, the patriot dismissing Christ's teaching as a noble but impractical doctrine. Few readers were troubled by such articles until the Spanish Civil War in 1936. The fascist side, led by Franco, presented itself as defender of the Catholic faith. Nearly every Catholic bishop and publication rallied behind Franco. The Catholic Worker, refusing to support either side in the war, lost two-thirds of its readers.

Those backing Franco, Day warned early in the war, ought to "take another look at recent events in [Nazi] Germany." She expressed anxiety for the Jews and later was among the founders of the Committee of Catholics to Fight Anti-Semitism.

Following Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and America's declaration of war, Dorothy announced that the paper would maintain its pacifist stand. "We will print the words of Christ who is with us always," Day wrote. "Our manifesto is the Sermon on the Mount." Opposition to the war, she added, had nothing to do with sympathy for America's enemies. "We love our country.... We have been the only country in the world where men and women of all nations have taken refuge from oppression." But the means of action the Catholic Worker movement supported were the works of mercy rather than the works of war. She urged "our friends and associates to care for the sick and the wounded, to the growing of food for the hungry, to the continuance of all our works of mercy in our houses and on our farms."

Not all members of Catholic Worker communities agreed. Fifteen houses of hospitality closed in the months following the U.S. entry into the war. But Day's view prevailed. Every issue of The Catholic Worker reaffirmed her understanding of the Christian life. The young men who identified with the Catholic Worker movement during the war generally spent much of the war years either in prison or in rural work camps. Some did unarmed military service as medics.

The world war ended in 1945, but out of it emerged the Cold war, the nuclear-armed "warfare state," and a series of smaller wars in which America was often involved.

One of the rituals of life for the New York Catholic Worker community beginning in the late 1950s was the refusal to participate in the state's annual civil defense drill. Such preparation for attack seemed to Day part of an attempt to promote nuclear war as survivable and winnable and to justify spending billions on the military. When the sirens sounded June 15, 1955, Day was among a small group of people sitting in front of City Hall. "In the name of Jesus, who is God, who is Love, we will not obey this order to pretend, to evacuate, to hide. We will not be drilled into fear. We do not have faith in God if we depend upon the Atom Bomb," a Catholic Worker leaflet explained. Day described her civil disobedience as an act of penance for America's use of nuclear weapons on Japanese cities.

The first year the dissidents were reprimanded. The next year Day and others were sent to jail for five days. Arrested again the next year, the judge jailed her for thirty days. In 1958, a different judge suspended the sentence. In 1959, Day was back in prison, but only for five days. Then came 1960, when instead of a handful of people coming to City Hall Park, 500 turned up. The police arrested only a few, Day conspicuously not among those singled out. In 1961 the crowd swelled to 2,000. This time forty were arrested, but again Day was exempted. It proved to be the last year of dress rehearsals for nuclear war in New York.

Another Catholic Worker stress was the civil rights movement. As usual Day wanted to visit people who were setting an example and therefore went to Koinonia, a Christian agricultural community in rural Georgia where blacks and whites lived peacefully together. The community was under attack when Day visited in 1957. One of the community houses had been hit by machine-gun fire, and Ku Klux Klan members had burned crosses on community land. Day insisted on taking a turn at the sentry post. Noticing that an approaching car had reduced its speed, she ducked just as a bullet struck the steering column in front of her face.

Concern with the Church's response to war led Day to Rome during the Second Vatican Council, an event Pope John XXIII hoped would restore "the simple and pure lines that the face of the Church of Jesus had at its birth." In 1963 Day was one of fifty "Mothers for Peace" who went to Rome to thank Pope John for his encyclical Pacem in Terris. Close to death, the pope couldn't meet them privately, but at one of his last public audiences blessed the pilgrims, asking them to continue their labors.

In 1965, Day returned to Rome to take part in a fast expressing "our prayer and our hope" that the Council would issue "a clear statement, `Put away thy sword.'" Day saw the unpublicized fast as a "widow's mite" in support of the bishops' effort to speak with a pure voice to the modern world.

The fasters had reason to rejoice in December when the Constitution on the Church in the Modern World was approved by the bishops. The Council described as "a crime against God and humanity" any act of war "directed to the indiscriminate destruction of whole cities or vast areas with their inhabitants." The Council called on states to make legal provision for conscientious objectors while describing as "criminal" those who obey commands which condemn the innocent and defenseless.

Acts of war causing "the indiscriminate destruction of ... vast areas with their inhabitants" were the order of the day in regions of Vietnam under intense U.S. bombardment in 1965 and the years following. Many young Catholic Workers went to prison for refusing to cooperate with conscription, while others did alternative service. Nearly everyone in Catholic Worker communities took part in protests. Many went to prison for acts of civil disobedience.

Probably there has never been a newspaper so many of whose editors have been jailed for acts of conscience. Day herself was last jailed in 1973 for taking part in a banned picket line in support of farmworkers. She was seventy-five.

Day lived long enough to see her achievements honored. In 1967, when she made her last visit to Rome to take part in the International Congress of the Laity, she found she was one of two Americans "” the other an astronaut "” invited to receive Communion from the hands of Pope Paul VI. On her 75th birthday the Jesuit magazine America devoted a special issue to her, finding in her the individual who best exemplified "the aspiration and action of the American Catholic community during the past forty years." Notre Dame University presented her with its Laetare Medal, thanking her for "comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable."

Among those who came to visit her when she was no longer able to travel was Mother Teresa of Calcutta, who had once pinned on Day's dress the crucifix normally worn only by fully professed members of the Missionary Sisters of Charity.

Long before her death on November 29, 1980, Day found herself regarded by many as a saint. No words of hers are better known than her brusque response, "Don't call me a saint. I don't want to be dismissed so easily." Nonetheless, having herself treasured the memory and witness of many saints, she is a candidate for inclusion in the calendar of saints. Cardinal John O'Connor, Archbishop of New York, launched the canonization process in 1997, the hundredth anniversary of Day's birth.

"If I have achieved anything in my life," she once remarked, "it is because I have not been embarrassed to talk about God."