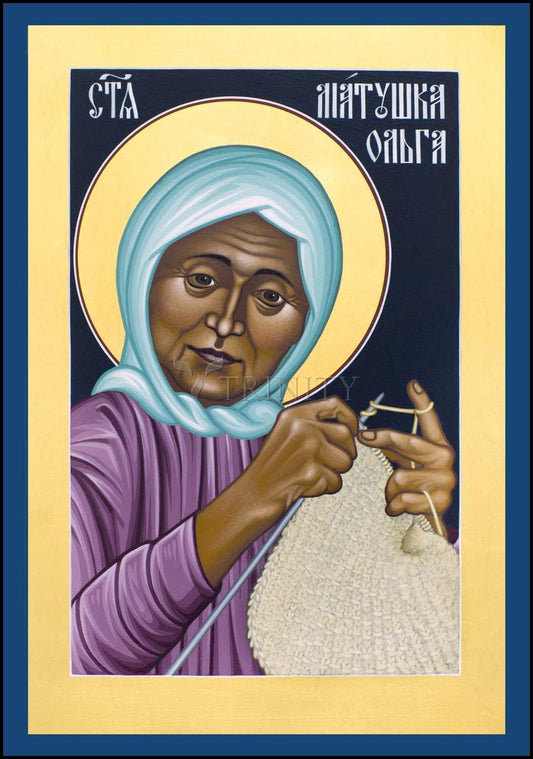

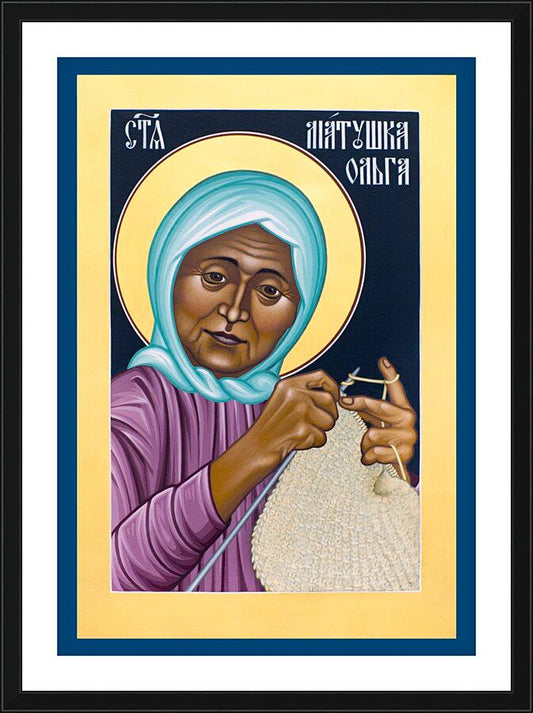

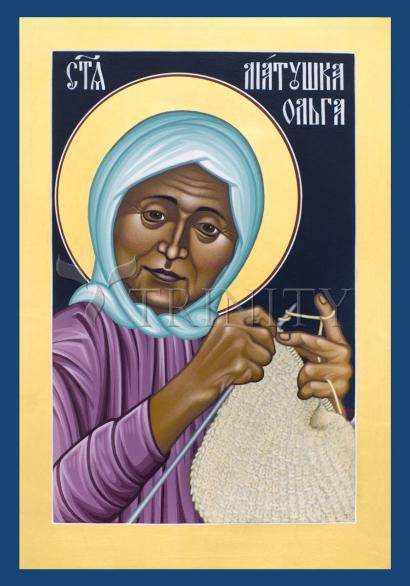

Matushka Olga Michael, also known as Olinka, was a priest's wife from Kwethluk village, on the Kuskokwim River in Alaska.

Matushka Olga was a Native Alaskan of Yup'ik origin. Her husband was the village postmaster and manager of the general store, and later archpriest, Fr. Nikolai Michael. Serving her community not only as a priest's wife, but also as a midwife, Matushka Olga gave birth to and raised several children, many of whom she gave birth to without the aid of a midwife of her own.

Matushka Olga was known for her empathy and caring for those who had suffered abuse of all kinds, especially sexual abuse. While her family was poor, she was generous to those who were poorer, often giving away her children's clothes to the needy. She was also known for her ability to tell when a woman was pregnant, even before the woman herself had missed her period.

When Matushka Olga reposed, many people from miles around wanted to come to her funeral, but since it was November, the winter weather made it impossible. But a wind from the south brought warm weather, thawing the ice and snow to make the trek to Kwethluk possible. When the mourners exited the church to take her body to the graveyard, a flock of birds followed. The ones who dug her grave found that the ground, too, had thawed. The evening after her funeral, the normal harsh winter weather returned.

Remembering Our Mother Olga

It is a joy to write to you about Saint Olga. She is a wonderful blessing to us and a model of the simplicity and spirituality possible today, even in the midst of modern life. I think her piety is best revealed in the Judgment Sunday gospel about Jesus separating the sheep and the goats. She led a very quiet life full of this kind of Christian love. Her life of deep and continuous prayer is evident through her actions while she was alive. Whatever the need and whatever the opportunity, she always put love of the other first.

She had deep empathy and discretion for all the people who came to her in need, especially the women she served as midwife. Often situations of sexual abuse would be made known only to a midwife. She would be the only person they could turn to and then only if they really trusted her. There were no resident Doctors and for a long time only a very small dispensary. I'm not at all sure how much of her healing, especially of women from abuse and rape, will ever be known to anyone other than the ones she healed. People in a small villages keep silent about this kind of pain even these days.

Theirs was a poor family too, but somehow that did not count with her. She lived in a three room house with no running water, no sewer connection and no furnace. This life style is still quite common in rural Alaska. She had to carry water every day for her eleven children. Her children remember her giving away their clothes, before they had outgrown them, to children in their village who were in greater need. She used to say to them, "If you see your dress on someone else, please don't mention it or say anything about it."

As Mother Olga becomes known to more and more people, her radical sense of our common life and sharing will become an important part of her gifts to us. God reveals his saints to us fully themselves and fully glorified. Mother Olga's Yup'ikness is part of her gift to us.

The Yup'ik Eskimos have a sense of community that I find quite amazing and is definitely part of the goodness of God that she brings to us. Very much like the early church, Yup'iks believe in sharing what they have. The worst thing I heard someone say to a two and half year old is that she was stingy about sharing her cookie.

Yup'ik generosity is not limited to the people who believe the same as you or to people who are related to you. There is a cherishing of each member of the village so that when one dies his or her name is carried on by the next children who are born. Probably the more treasured one is the more babies are named after you.

There is also an acceptance of responsibility for that baby on the part of the deceased's family, so that the baby is looked after. Most importantly, the baby and the baby's family are fed by the men in the deceased's family. A part of any successful hunt will go to feed the baby and its family year after year.

The child's name day is an occasion for a feast to which everyone in the village is invited by the child's family. The child's family also feeds and helps look after the widow or widower as a way of taking care of their baby's connections in this life.

Mother Olga's Yup'ik life also models for us the eternal value of understanding our relatedness one to another. God will use the example of her whole life to draw us closer to His goodness, His bounty and His loving will for us. Our ways of honoring that relationship will be different, but I think her example asks us to examine the depth of our love for each other and our faithfulness to the call to love God in our neighbor.

It is her deep spiritual life that guided her through the transition from a completely traditional life style to one comfortable in the modern world. Here, too, her example of inner calm and spiritual steadfastness is a strong part of her gifts to us. She hid her life in Christ, was very humble and unassuming, very quiet. Visitors to her house, while her husband was the priest in Kwethluk, say that she was almost invisible, so gentle and complete was her sense of hospitality and service.

She lived a life of deliberate generosity. Once she told one of her daughters to invite a specific girl home to play. This child was being neglected and badly treated at home. Alcohol and child abuse happen in small villages too. Mother Olga knew that the girl had been told not to eat at anyone's house so she cooked potato pancakes and, keeping her back to the table, kept piling them on a plate from the stove. Her daughter whispered to her that the little girl was stealing the food. This is a big no-no in a culture which sees greed as a major failing. Mother Olga put her finger to her lips and shushed her daughter asking if the little girl was still eating. With each yes, she cooked more pancakes and put them on the table until the little girl was full. For her love came first even above cultural norms and supposed righteousness. This little story is very healing for anyone who has suffered from deprivation and neglect as a child. Saint Olga is a saint they can turn to for healing from the pain and loneliness, and especially the lost self-esteem that is the result of neglect and abandonment.

She never criticized her children and gave them great freedom and respect. One of her daughter's friends told me that they used to go over to play at her house and leave all their toys out, but Mother Olga never said anything. After a few years, the girls realized that they had been making a lot of work for her and began to put the toys away themselves. Saint Olga's way was to understand what children were capable of doing and let them become responsible for themselves. She believed in not forcing them to conform to her set of rules whenever possible and never using shame to discipline. This, too, is a very Yup'ik way of child care when the cultural expression of that is intact.

As they grew so did the expectations. When her girls were big enough, she would ask them to accompany her to do housework for the ill and old people in the village. When they were old enough, they went wherever she saw the need. Sharing didn't just mean clothes and food but also time and effort. She taught what it means to be a fully alive human being, connected to people through love and service by example. She was good at many kinds of hand work, sewing and knitting mostly.

People remember her stopping whatever she was doing in order to help anyone with just about anything. I think she was aware of Jesus in all the people she saw but I think she was very simple about it. She didn't talk a lot. She just would go ahead and do what was needed. She would stop whatever she was doing to finish a snow boot sole that was too difficult for her friend, knowing a leaky boot meant death for the wearer.

For many years several times a week, she hauled wood and water to make a steam bath to share with a friend who was blind. She used to make traditional fur boots and parkas as donations to be raffled by other communities around Alaska which were trying to raise money.

Mother Olga was in the first generation of people in her village to be baptized Orthodox as a child. She was probably one of the few people who lived both in the traditional ancient world of the Yup'iks and in our modern one. So it isn't surprising that when the Theotokos revealed her to us the context of the healing was so traditionally Eskimo.

The "hill house" mentioned in the account is the way her ancestors had lived. The geographic descriptions of her walking a long way to a place where there were no trees is what one does leaving her village to go out to the tundra. The rose, violet and pine scent mentioned in the account is actually the smell of Labrador Tea which grows wild on the tundra and which the person receiving the healing had never smelled.

Mother Olga was a midwife and a healer. She was known for her foreknowledge of who was pregnant even before they had missed a period. The current priest's wife, Mathushka Helena Nicholai, told me that Mother Olga had told her not to carry any more water buckets for a while because she was pregnant. Matushka Helena didn't have any idea she was pregnant. Mother Olga also knew who would need to plan for a difficult pregnancy. She sent some women in to the larger town of Bethel for hospital care long before anyone could have known they would need it. Now a days, the hospital in Bethel requires that most people spend their last trimester in town awaiting delivery there since transportation is so difficult. There are no roads. In summer you can go by boat but most of the year the river is frozen and the weather very unpredictable. None of these things were known to the person who received healing through the vision of Mother Olga.

A woman of deep prayer, Saint Olga knew the words of all the services of Pascha by heart in Yup'ik. She had an arranged marriage which was not easy in the early years. Her husband was the local Postmaster and much later in life became a priest who served Kwethluk well of many years. There is a sense among those who knew the Michael's that Saint Olga's prayers for her husband brought him to faith in God and eventually brought him to choose to serve God as a priest. The life of an Alaskan village priest means that he will have to travel many miles to serve other outlying parishes and be gone for long stretches of time. Still her love for the church and the people was never diminished by the hardships she had to endure.

Local veneration of Mother Olga is already a part of the way her village remembers her and her husband. One of the things people do in the village at Christmas is to go starring (caroling) from house to house. They stop at the homes of people who have died that year to sing Memory Eternal, but just that year. They have been singing at her house for twenty years, even when it has stood vacant, for love of her.

When she died in November, it was already deep winter in Kwethluk. The river was frozen but not solidly enough for snowmobiles to cross safely. Many people had wanted to come to her funeral from many of the outlying villages but could not get there. The weather suddenly changed and a warm south wind began to blow. The river thawed and the people came. The earth unfroze. The men who had gone out with pick axes to dig her grave found the earth was already soft and ready to receive her. A flock of summer birds, normally long gone, followed her body from all the way from the new church to the old burial ground. After her funeral feast was over and the people safely gone, the wind blew cold again and the summer birds disappeared. Winter returned and the temperatures fell to far below zero again as was normal for that time of year.

Kwethluk, her village, produced an amazing number of seminarians who went to St. Herman's Theological Seminary during her life time. During Saint Olga's lifetime, the village of Kwethluk whose population in those days was about two hundred sent more than twenty men to seminary to become readers, deacons and priests. There is no other place in Alaska that shown such a dedication to serving God during one person's life.

One man, Father Stephen Epchook, had walked away from his people and his faith even though both his father and grandfather had been priests. Mother Olga died while he was away. Finally, he came back after many years and went to seminary. One can't help thinking that she never stopped praying for him.

During his last year of seminary, while on trip to St. Vladimir's in Crestwood, New York, Mother Olga showed him her great love and joy in him in an extraordinary way. A woman was in the bookstore at the same time Father Stephen was. She was ignorant of the way Yup'ik Eskimos looked and had taken him for Chinese, thinking he was from Shanghai. She had been praying to Mother Olga for a way to express her gratitude to her for her healing love. Something prompted the woman to keep part of her attention on this middle aged priest as he scanned the shelves for the right book. She saw him find it, turn it over for the price and start to put it back. She knew he was meant to have that particular book and rushed down the aisle to ask if he would allow her to give it to him.

With the dignity of one who understands the importance of sharing to the giver, he accepted. The book turned out to be the Gospels Father Stephen wanted to use in his new parish. Imagine her surprise to find out that the Chinese priest was really Yup'ik and from Mother Olga's tiny village so far away. If Father Stephen had gone to Seminary in the usual order of things, Saint Olga would have been alive and able to give him a graduation gift herself. Fifteen years later she did.

Many women who read the account of Saint Olga's healing are deeply drawn to her strength and her honest clarity about who is responsible for the sins committed and who is really the guilty. The person who is abused and raped is the person who is sinned against and the deeper healing comes with the recognition that every sin is ultimately against Jesus. He is the provision for that sin. If we feed Jesus in the hungry, cloth Him in the naked, visit Him in prison and in the sick, then just as surely as we minister to Him in our neighbor, we also hurt Him in our neglect of our neighbor.

When we think about rape and abuse, then, Mother Olga teaches us to recognize Him as the One who is abused and raped too. Christ in us is our hope of glory. Christ in us is the sinned against. Christ carries away that sin and restores to us His own and His Mother Mary's original purity and beauty through the loving intercessions of Saint Olga for us all.

—Excerpts from Testimony Written 1999 February by a Pilgrim to Kwethluk

Born: February 3, 1916

Died: November 8, 1979