Listen and let it penetrate your heart"do not be troubled or weighed down with grief. Do not fear any illness or vexation, anxiety or pain. Am I not here who am your Mother? Are you not under my shadow and protection? Am I not your fountain of life? Are you not in the folds of my mantle? In the crossing of my arms? Is there anything else you need?" (Our Lady's words to her servant Juan Diego.)

The First Apparition

Juan Diego awoke before sunrise. It was Saturday, Our Lady's day, the ninth of December, the first day in the Octave of the Immaculate Conception, 1531, and quite cold in the mountains of Mexico at that time of year. Wrapping his cloak or tilma about him Juan set out alone from his new home in Tolpetlac to the neighboring village of Tlatelolco, a suburb of Tenochtitlan, six miles south. He was on his way to Mass, which he had faithfully attended every Saturday and Sunday since his conversion six years before. It was a long journey for anyone to make two days in a row; that's twenty-four miles of walking, and his aging limbs were beginning to feel the toll. The trip seemed so much longer since his wife and traveling companion, Maria Lucia, had died two years ago. Now he walked the road alone. But being alone had its advantages; it gave him time to think about and talk to God. The good friars had taught him well how to do that.

It was still dusky, not too far from dawn, as he approached Tepeyac hill. Here not so long ago stood the gory temple of the Aztecs' mother goddess. It was just a memory now as were all their false deities. But Juan's thoughts were elsewhere as he shuffled along on his way to Mass; the kind Fathers expected him to know his catechism lesson and these eternal truths preoccupied his mind.

Suddenly his thoughts were interrupted by music, very wonderful music, descending from atop the slope of the hill. It sounded to him like a mellifluous chirping of sweetly singing birds. It was a melody such as he had never heard. The tones began to grow more enchanting, filling the air around him and so enrapturing his soul that he began to doubt whether it was possible for a man in this fragile life to relish such exquisite harmony and remain in the flesh. "Is it I," he wondered, "who have this good fortune to hear what I hear? Or am I perhaps only dreaming? Where am I? . . . Is this perchance the earthly Paradise hidden from the eyes of men?" The ravished Indian squinted his eyes to scan the hilltop, when to his utter astonishment, a cloud glowing with dazzling whiteness appeared just above the crest, while a magnificent rainbow formed by its resplendent rays emblazoned everything around it. Then, abruptly, the celestial singing ceased. A voice was heard from within the cloud. It was the voice of a young woman, a tender voice, calling his name most affectionately, "Juanito, Juan Dieguito."

Our Lady spoke to her humble protégé in his own Nahuatl tongue. In that language the form of address used by the woman had a significantly more singularly intimate than any expression English or Spanish could convey. The exact sound that met the Indian's ears was "Juantzin, Juan Diegotzin." It was an endearing expression, reverently diminutive, that a fond mother would use for her child. English would render it: "Dear little Juan." That same voice beckons each of us with an identical tone of affection. If only more men would open their hearts to hear the call, what joy it would bring into their lives!

Totally perplexed, the fifty seven year old Juanito clambered up the rocky incline to see who it was who so sweetly addressed him. Strangely though, there was no fear in him; he was supremely confident, and intoxicated with exuberance.

As he reached the summit, the voice gently bade him draw near. Doing so, he found himself face to face with a woman of incomparable loveliness, whom he described simply as "a most beautiful lady." Her garments shone so brilliantly that the entire mountain was transformed by the reflection of her glory. The rocks became as precious gold; the earth sparkled like emeralds and multi-colored jewels; even the shrubs and prickly pears were splattered with a sheet of color, as if their thorns had been changed into stained glass.

She was young, perhaps fourteen, her expression most affable and encouraging. She motioned Juan to come closer. Advancing a step or two he sank to his knees, overwhelmed by the loveliness of the vision.

The Lady spoke, " My son, Juan Diego, whom I tenderly love as a little one and weak, where are you going?"

And he replied, "My holy one, my Lady, my Mistress, I am on my way to your house at Tlatelolco; I go in pursuit of the holy things which our priests teach us." His holy one, the noble Lady, then revealed her will saying:

"Know my son, my much beloved, that I am the ever Virgin Mary, Mother of the True God who is the Author of life, the Creator of all things, the Lord of heaven and earth, present everywhere. And it is my wish that here, there be raised to me a temple in which, as a loving mother to thee and those like thee, I shall show my tender clemency and the compassion I feel for the natives and for those who love and seek me, for all who implore my protection, who call on me in their labors and afflictions: and in which I shall hear their weeping and their supplications that I may give them consolation and relief. That my will may have its effect, thou must go to the city of Mexico and to the palace of the bishop who resides there, to tell him that I have sent thee and that I wish a temple to be raised to me in this place. Thou shalt report what thou hast seen and heard, and be assured that I will repay what thou dost for me in the charge I give thee: for I will make thee great and renowned. Now thou hast heard, son, my wish. Go in peace. . . employ all of the strength thou art able."

Juan bowed low in humble obeisance and said, "I go, I go, my most noble Lady and Mistress, to do as a humble servant what you have ordered. Farewell."

After Juan had spoken to Our Lady, he straight-away set out on his mission, as a most obedient son, and took the road leading directly to Mexico. Juan never paused to weigh the pros and cons of his own insufficiency; he just did what he was commanded, and he acted promptly; any obstacles he would face when and where they came.

This past December 12 [1981] marked the four hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the apparitions of Our Lady of Guadalupe to the humble Aztec Indian Juan Diego on Tepeyac hill near Mexico City.

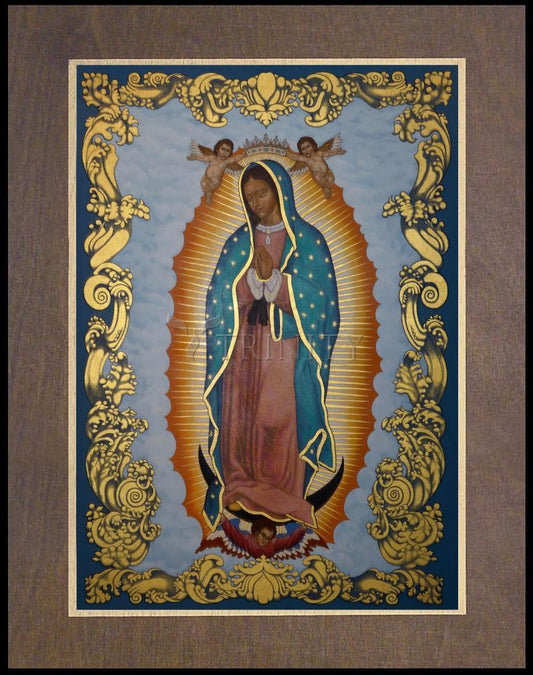

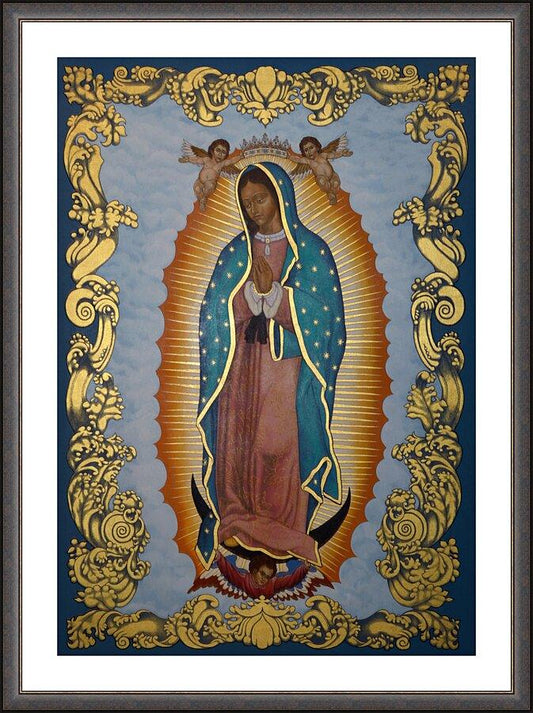

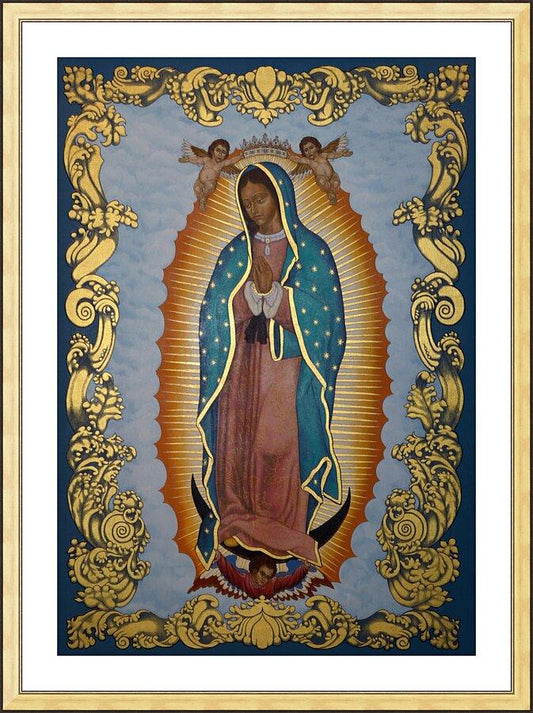

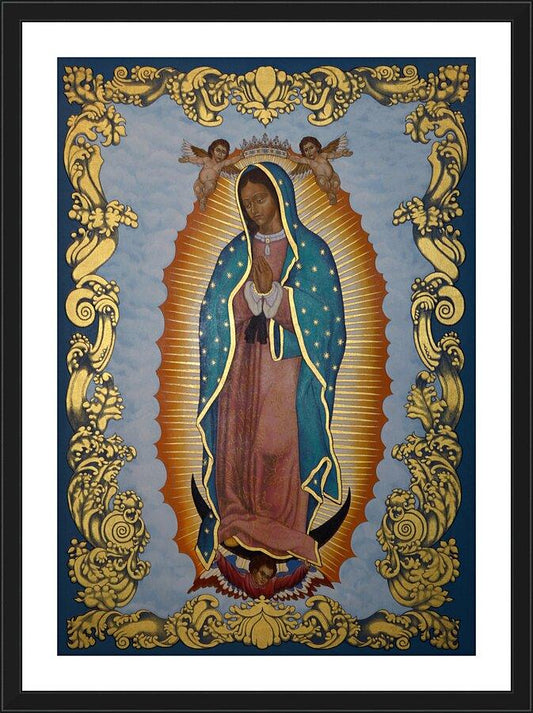

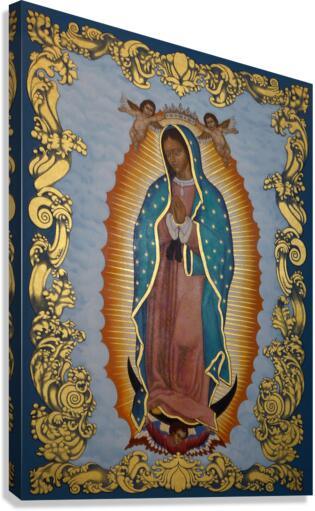

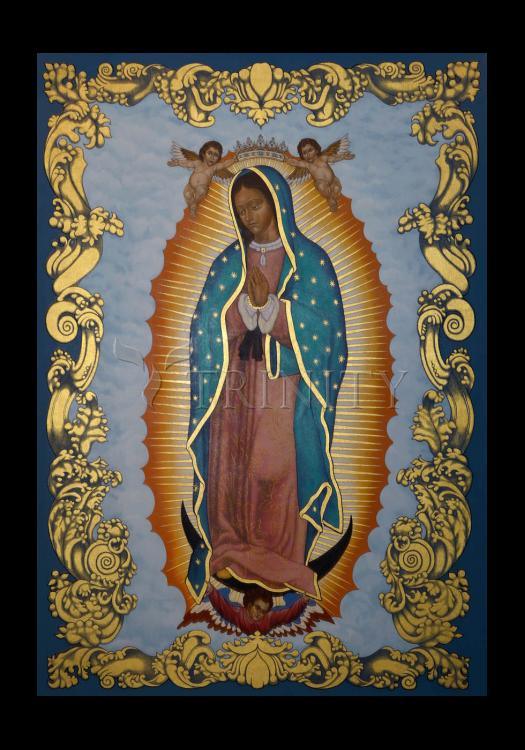

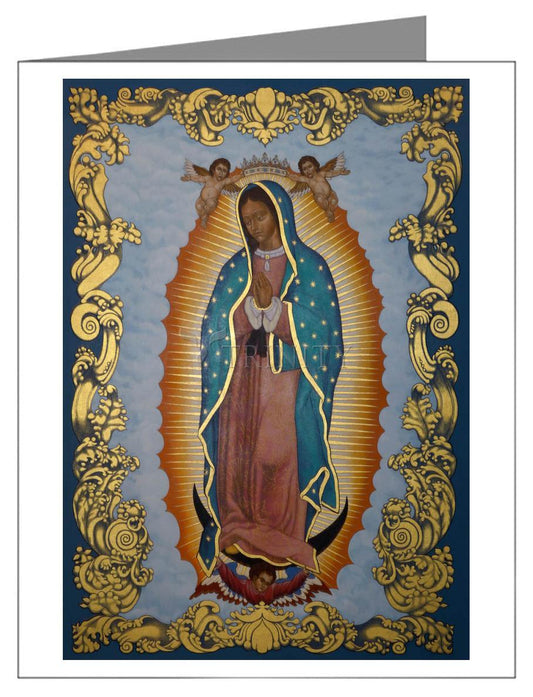

Her message was beautiful and simple. She told him that she wanted a church to be built in her honor on this hill, wherein she would receive and compassionately console all her suffering children. For this purpose she sent Juan Diego to the Bishop of Mexico, the Friar Minor, Don Juan de Zumarraga, to present to him her request. Though he was most faithful in his mission, the lowly messenger was not believed. Finally, Our Lady gave him a sign to take to the Bishop, a bouquet of flowers that she had caused to spring miraculously from the hilltop's frozen winter soil. And, to leave absolutely no doubt that it was indeed she, the Mother of God, who requested this church, she left imprinted on the face of the Indian's cloak, in which as an apron he had carried the miraculous sign into the prelate's presence, a full length color portrait of herself, just as the Indian had seen her. The tilma and its image can be seen to this very day in the cathedral of Mexico City.

Every year up to twenty million pilgrims come to Mexico's capital from all over the world to see and pray to Our Lady before her miraculous picture. Her shrine attracts every type of visitor imaginable, from chest-beating penitents to cold sophisticated worldlings; from irreverent gum smackers in tight jeans to the simple ordinary worshiper. They all come, representing a vast cross-section of humanity, all the time, in a never-ending stream. Some approach for hundreds of yards on their knees with arms outstretched in a posture of penance. Others, who have not such a visible conviction, at least come in prayer, perhaps reciting the Rosary, to prepare for their climactic encounter. Too many, sad to say, approach as mere tourists with no faith and no love, like orphans who do not want a mother. But here Our Lady has made herself available to all, the just and the unjust, to be loved or just viewed. And isn't it beautiful that she is always there, faithful to her promise to her "dear little one," Juan Diego, even after four and a half centuries.

Guadalupe is the most frequented Marian shrine in the whole world. The Blessed Virgin receives here three times more pilgrims than she does even at Lourdes. Is it because of the cures? No". There are cures, but that isn't why so many are drawn here. There's another reason, a more wonderful one, that gives Guadalupe such a compelling magnetism. It is the sense of Our Lady's presence.

There is a very real communication of hearts at Guadalupe. It is the heart of a sinless Mother seeking out the love of her children and offering her maternal protection. She, the Mother of God, wants to be known and loved by men so that she can lead them to her Son. She wants to be known for what she truly is. Now Mary knows her children only too well " but her children do not and cannot know her well enough, for there is so much to know about her that the pursuit would exhaust a whole lifetime of effort. But we must try. "They that explain me shall have life," the Scriptures say of Mary in the Book of Wisdom. So, in the vehemence of her tender love, those four centuries ago, she left for the world a portrait of herself painted with brushes "not of this earth." In this marvelous picture-it cannot be called a painting, for there were no paints involved-one can see for himself what the most beautiful creature God ever created looks like.

Then there is the canvas the Queen of Heaven chose for her portrait, the tilma of Juan Diego, a rough burlap-type cloak that the lower-class Indians wore draped over their shoulders, and ankle-length. Having been poor in her mortal life, the Mother of God did not disdain such a canvas, for by it she would confound the laws of science.

Every artist who has examined the tilma has affirmed that there simply is no way short of a miracle for such an exquisite picture to have been painted on such a coarse and porous surface. Furthermore, the tilma itself, made from cactus fibers, should have fallen apart, naturally speaking, twenty or thirty years at most after it was made. Nevertheless, long defying the laws of decomposition, it hangs together to this very day. Needless to say, if the canvas has been miraculously preserved, so has the image. The colors are still as fresh and vivid as when they first appeared, despite the natural corroding effect of black smoke, which for a century arose before it from hundreds of burning vigil lights (it wasn't until 1647 that the precious relic was put under glass), and despite the accidental spilling of a bottle of nitric acid across its surface by a workman in 1791.

The Mexicans are an extremely religious people. And they should be. After all, Pope Benedict XIV said, when a copy of the miraculous picture was first shown to him in 1754, "Non fecit taliter omni nationi," "God has not done in like manner to every nation," applying to the Mexicans this verse from Psalm 147.

And the cause of such holiness-to be seen more in the heart of the country than in the border cities-is none other than Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe. Her coming in 1531 was the birth of Mexico. That is why the secret forces of Masonry, in their efforts to destroy the Catholic principles upon which this nation rose up, have attempted with no success to destroy the Sacred Image. But neither with bombs, as was attempted during the Calles persecution in 1921, nor with the invectives of the liberal press, were they able to defeat the Virgin. In fact, as experience has taught her enemies, the more she is attacked, the more strongly will her children rise up in her defense.

Mexico and Our Lady of Guadalupe go together like the sun and its rays. You can't separate the two. She is enthroned in her country everywhere you turn. Whether you are in a grand cathedral, a busy market place, or a taxi-cab, you will always find her. She is the very air the Mexicans breathe. And what is even more beautiful is the way she sweetly reigns in the Mexican home. Nothing is more charming, more heart warming, than to see the joy, peace, modesty and cleanliness that come as second nature to a typical Catholic Mexican family. Here under her watchful eye all the bad fruits of worldliness and vice dare not appear. Instead, respect for parents, love for children, pleasant manners, tidiness, the modesty of the women, the purity of the men, the holy joy of all, can be seen in everything they do: in the way they work, in the way they entertain one another, in the way they eat their meals, and in the way they pray. Again the reason for such a blessing is their love for Our Lady of Guadalupe. "Come the day," admitted the skeptic Altimirano, "on which the Virgin of Guadalupe is no longer venerated, and you have the sign that the very name of Mexico has disappeared from the catalogue of nations!"