The Myth

The Quetzalcoatl Myth is the Great Epic of Mesoamerica. It describes events which took place in the city of Tollan Xicocotitlan (Tula, Hidalgo) in the north of the Valley of Mexico near the end of the Tenth Century. Long thought to be completely mythological, modern research from the 1930s onward has provided a solid factual basis for some of the key events. Much, however, remains wrapped in mystery. All we have to tell us of the legendary Ce Acatl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl comes from a handful of pre-Columbian sources (perhaps no more than twelve), subsequent Aztec accounts written 500 years later (heavily influenced by Christianity), and the archaeological record (extremely fragmentary).

No complete written version of the Myth survived the Spanish Conquest in 1519, with the possible exception of the "Legend of the Suns," a pictorial account much like the Mixtec codices. Although the original text did not survive the book-burnings, we do have an Aztec priest's account of the story which appears to have been the priest's explanation of the pictorial book.

Mixcoatl

The myth begins, like so many other myths, before the birth of its central figure, Topiltzin. We are given a short account of the events of Topiltzin's father's life, the famous Mixcoatl. Mixcoatl often appears in the Mixtec codices, as well as the Aztec's mythology. His name --"cloud serpent"-- may be more of a title than an actual name, just as Quetzalcoatl -- "feathered serpent"-- was a title held by many different rulers during the Toltec era. Mixcoatl may have been a Chichimec lord, or a ruler of the early Toltec capital of Culhuacan. Still considered to be mythological by many experts, Mixcoatl is something of a misty figure: he is frequently mentioned as being the father of Topiltzin and legend has it that a huge statue of the god-king was to be found at Cholula, a city closely associated with the Quetzalcoatl cult. Wherever he came from, he was clearly a powerful warlord by the time of Topiltzin's birth.

Mixcoatl proceeds to make conquests, eventually becoming powerful enough to marry into the early Toltec aristocracy. His young wife, Chimalman, a princess of the branch of the Toltecs who ruled Culhuacan, gives birth to Topiltzin, who bursts from her chest fully armed and prepared to join his father Mixcoatl's armies. Chimalman dies four days after Topiltzin's birth, a fate which many women suffered in pre-Columbian (and post-Columbian) Mexico.

Legend places his birth at Xochicalco, the great Classic Era city. Topiltzin proves himself an able warrior at a very young age, taking captives for sacrifice at Xicalanco, a place whose physical location has not yet been identified. Mixcoatl and his son wage numerous successful campaigns, creating a Toltec empire which encompasses most of the Valley of Mexico. The archaeological record supports such a series of conquests, as it is about this time (c. 950AD) that we see an explosion of Toltec influence in Mesoamerica. In fact, it is about this time that we see the "War of Heaven" taking place in the Mixtec codices (Nuttall, Vindobonensis), as well as pronounced Toltec influences at El Tajin.

It is very likely that some of these conquests (though most likely the conquests were in a limited geographical area) were lead by Mixcoatl. Even if we do not have definitive, exact descriptions of his military campaigns, it does seem clear that Mixcoatl was a very successful warrior, in that his name was remembered for 500 years.

The Mimixcoa

But Mixcoatl is eventually betrayed and murdered by his 400 brothers (the Mimixcoa) who then go in search of Topiltzin intending to kill him as well. A civil war ensues in which Topiltzin tricks his uncles in a battle on top of a temple, and sacrifices them by cutting them open and smearing their bodies with chili peppers. After his victory, he hunts down the rest of his uncles, kills them, and then recovers his father's bones which the Mimixcoa had hidden. He founds a great temple as memorial to his father. He then sets off to "make conquests," in the words of the anonymous Aztec priest who interpreted the "Legend of the Suns" to the Spanish.

Conquests

Topiltzin, now at the head of elite groups of the Jaguar and Eagle warrior cults, drawn from the unified Toltec nations, proceeds to make conquests in the Valley of Mexico, Puebla, Cholula, and along the Gulf Coast at Coatzalcoalcos. After annexing the Itza people and their merchant fleets at Acallan, Topiltzin and his armies reach as far as Chichen Itza, the capital of the Yucatan Maya. Topiltzin conquers the Maya, and builds an exact duplicate of his capital at Tula near the sacred Well of Sacrifice at Chichen Itza. Now known as Kulkulcan, the Feathered Serpent, he apportions kingdoms to his new allies and loyal followers such as the Jaguar Priests of the Quiche Maya, whose history is recorded in the Popol Vuh. At last, after years of war and conquest, he dies in Acallan --the land of the Red and the Black, the Maya Country.

Tezcatlipoca

But the empire Topiltzin left behind is soon wracked by internal power struggles. A strange Chichimec sorcerer, Tezcatlipoca, has come from the North. He proceeds to work mysterious and evil deeds upon the Toltecs. He disguises himself as a naked Huaxtec merchant in order to seduce Huemac (Topiltzin's heir), Quetzalcoatl's daughter. He changes himself into a great corpse whose decomposition sickens and kills the Toltecs.

He shows Huemac his own reflection in a "smoking mirror" in which Huemac sees himself as he has truly become: old, frail, ugly. Tezcatlipoca convinces Quetzalcoatl to take a few sips of a sacred wine, and then to have more, five cups in all.

A drunken Huemac commits incest with his sister and falls into deep spiral of remorse. Many more of the Toltecs die, victims of Tezcatlipoca's malice which Huemac Quetzalcoatl, now grown old, is unable to combat. The Huaxtec trader mentioned before becomes a powerful warlord despite Huemac's attempts to send him to his death in battle, and Huemac's power further weakens.

The Fall of Tollan

Sensing the imminent collapse of his empire, Huemac causes the city of Tollan to be razed rather than let it fall into the hands of Tezcatlipoca and his followers, the Chichimecs. All the great temples are destroyed, all the sacred books and treasures of the realm are hidden high in the mountain valleys. Huemac and his few loyal followers flee the ruined capital towards the Gulf Coast. At every stop, Huemac is harassed by the demonic minions of Tezcatlipoca, and is forced to give up his knowledge of craft and science and the arts. Huemac's loyal Nonoalco followers, forced to flee with him, perish one by one in the cold passes between the Volcanos Ixtaccihuatl and Popocapetl.

Arriving broken, powerless, and alone on the Gulf Coast at Acallan, Huemac immolates himself in a sacred bonfire and rises up to become Venus, the Morning Star. Or flees to Chapultepec and hangs himself. Huemac is referred to as "Quetzalcoatl" in the Florentine Codex, which has caused endless confusion between him and his father Topiltzin. Whichever the case, with the death of Huemac, the Toltec Era comes to an end.

Such is a highly romantic reconstruction of the Quetzalcoatl Myth.

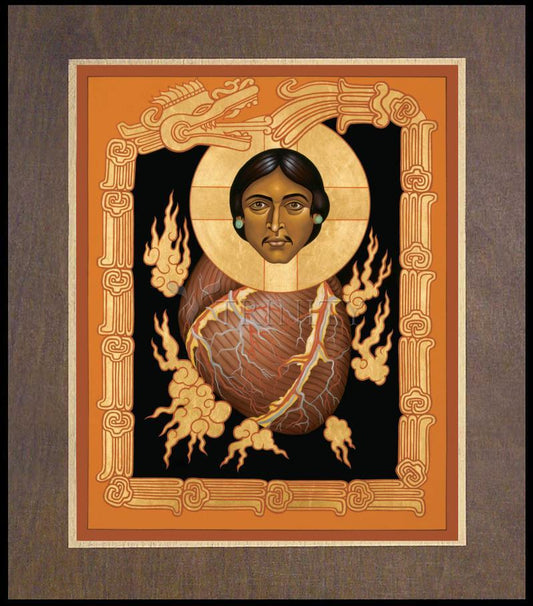

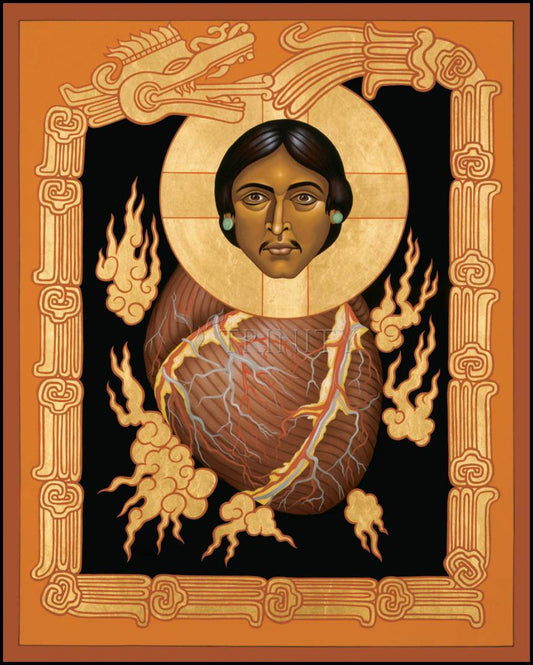

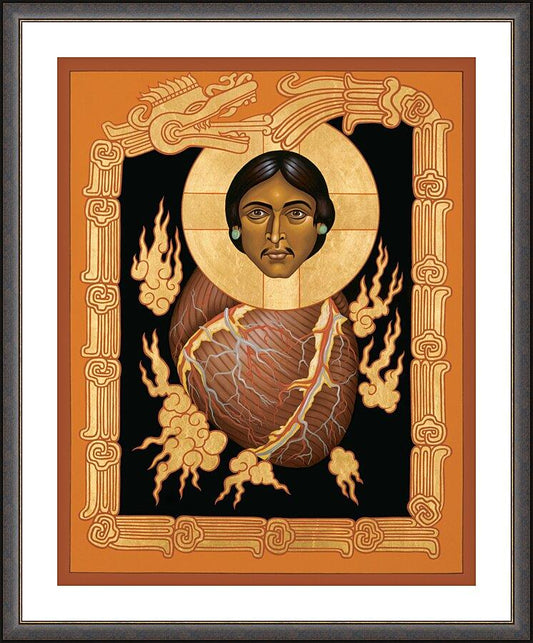

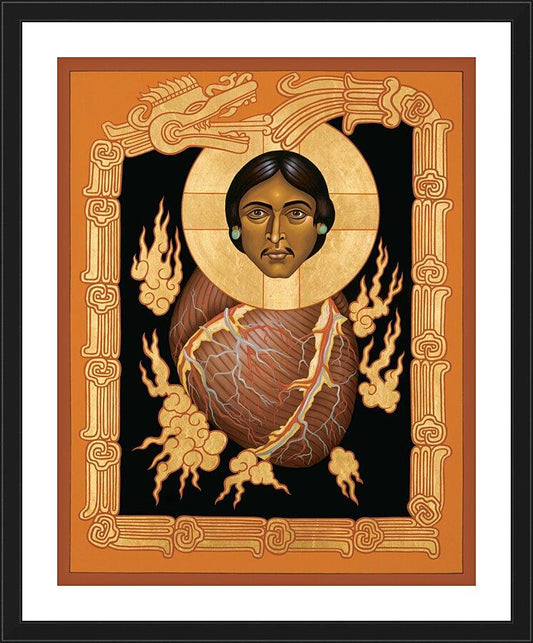

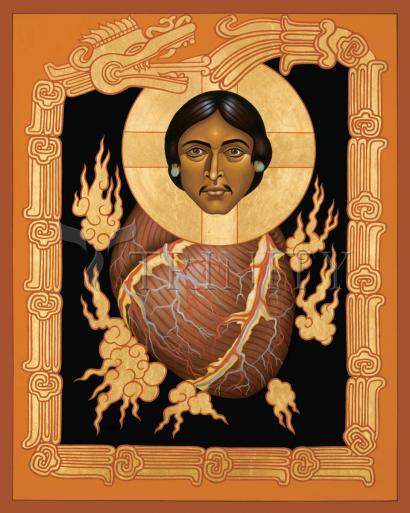

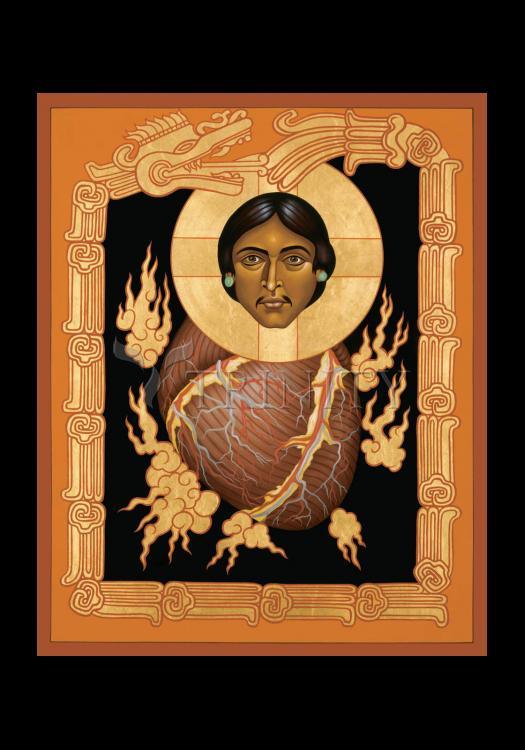

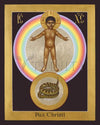

A Mesoamerican Christ

Quetzalcoatl is to the New World what Christ is to Europe: the center of a religious cosmology and the pre-eminent symbol of the civilized nations of Mesoamerica. Both were considered to be men who ascended into heaven upon their death; Christ to sit at the right hand of God, Quetzalcoatl to become the Morning Star. Both were tempted by evil powers; Christ by Satan, Quetzalcoatl by the wizard-god Tezcatlipoca. And both were prophesied to one day return to earth, Christ as the Prince of the Kingdom of Heaven, Quetzalcoatl as a god-king returned to claim his kingdom in Central Mexico. To understand the life and teachings of Jesus Christ is to understand Christianity, the root religion of what we refer to as Western Civilization. To understand the life and mystery of Quetzalcoatl is to understand the religious thought of what we call Mesoamerica.

The Feathered Serpent

The figure of the feathered serpent predates Topiltzin by at least 500 years. With an archaeological history stretching from the Temple of Quetzalcoatl (100-200AD) at Teotihuacan until the founding of Tula Tollan (c. 700AD), and a written history extending from the beginnings of the Toltec state to the end of the Aztec Empire (1520), Quetzalcoatl is the best known of the pantheon of gods who appear throughout pre-Columbian archaeology. In the days after the fall of the Toltecs, Quetzalcoatl as the Feathered Serpent became the symbol of legitimate authority, a kind of coat of arms for any ruler who pretended to power beyond the circuit of his own walls. The Aztecs considered themselves the descendents of this political tradition, even if Huitzilopochtli (a later version of Tezcatlipoca) had become their primary tribal god.

Who is the god Quetzalcoatl? Very little has come down to us 500 years later. The physical evidence of stone carvings and glyphs is weathered and often extremely difficult to decipher, the written evidence has been destroyed, altered or perhaps never existed at all. A long-nosed god appears on stelae at Tikal and Quiriga and several other Maya sites, perhaps as a direct influence the Olmeca-Xicallanca, but this god may not be Quetzalcoatl and indeed has few of the monumental aspects of the flying serpents of Teotihuacan. The descendents of the builders of the Pyramids of the Sun and Moon carved snake heads surrounded by feathers on their Quetzalcoatl Temple, but had no identified system of writing which might have cast light on the role of the worship of the plumed serpent in their gigantic city of Teotihuacan ("where the gods were made").

What is clear however is that the plumed serpent was a symbol of political power, and wherever he appeared carved in stone, signs of ritual human sacrifice would be found nearby. Many researchers who had believed in a more peaceful, mercantile-based society at Teotihuacan were startled by the discovery of over 200 sacrificial victims buried at the corners of the Temple of Quetzalcoatl in 1988, most warriors with their hands tied behind their backs. It is clear that by this time (c. 250 AD), Quetzalcoatl had assumed major importance and a military cast, being the god of warriors rather than priests. It appears that Quetzalcoatl continued to be the focus of religious worship until the fall of the city sometime in the 8th century, an event which is considered to be the birth of the Fifth Sun, the Sun of the Toltecs.

The Texts

Did Quetzalcoatl have his own developed mythology at Teotihuacan? If so, was it a lost original of the later tale of the god-king of Tula? Repeated motifs are common in Mexican mythology. The story of the 400 brothers of Mixcoatl has an exact parallel in Aztec mythology, as does the story of Quetzalcoatl bursting from his mother's chest, only called Huitzilipochtli.

The literature which was passed down to succeeding generations of Toltec/Chichimec/Mixtec/Aztec priests was transmitted by means of "magic books", books painted on gate-folded animal skin or bark using pigments and plant dyes. These books do not have accompanying written "text" in the same sense as modern books, however. They have been thought to function as "guides" or supplements to oral tradition. The Toltec and Aztec magic books which might have contained illustrations of Quetzalcoatl legends handed down via oral traditions from previous eras were for the most part destroyed by Spanish priests (and by the Aztec's enemies) who followed after Hernan Cortes and the conquistadors.

These priests, bent on suppressing and then eliminating a religion which they viewed as "satanic" and whose chief gods were considered "demons", were only too successful. A bare handful of pre-Columbian codices survived, the most significant of which produced by Mixtec artists in the Valley of Oaxaca, the valley given to Hernan Cortes as a consolation prize. Perhaps out of a sense of admiration for the cultures which he had helped to obliterate, or perhaps as an attempt to further impress the Spanish Crown with the legends of the peoples he had conquered, Cortes sent several of these codices to Europe in the early days of the Colonial Era which is how the Codex Nuttall, and perhaps the Codex Vindobenensis I survived the bonfires. These books, however, appear to deal with the Toltecs descendents, and only refer back to the days of Quetzalcoatl in mythological terms.

The Spanish Priests

Much has been made of the book-burnings. In defense of the Spanish clergy it is difficult to expect that priests, friars or even well-educated bishops such as Diego de Landa could have understood or appreciated or even tolerated a religion which represented its most sacred deities as complicated monsters frequently shown consuming their worshippers. The priests of this religion also performed human sacrifices by excising the living heart from the chest of captives taken from enemy tribes. That these priests worshipped in temples decorated with the dismembered remains of those sacrifices (as reported by Bernal Diaz, one of Cortes' soldiers) convinced the earliest of the priests and soldiers that the Mexicans were not human.

To the early Spaniards, it must have appeared as if the whole of Mexican religion were dedicated towards providing sacrifices for their frightening gods under the implicit threat that if these sacrifices were not provided, the gods would allow the sun to fail, bringing the world to an end. Which, assisted by the Spaniards, it did.

The Aztecs

But what the Spaniards saw was an aberration, a distorted Aztec version of an earlier religion. Even the neighboring states, who practiced similar sacrifices, regarded the Aztec's wholesale massacres of thousands of victims as abhorrent, one of the many reasons they were so willing to help Cortes in his campaigns against the Aztecs.

It is no surprise that these nations were willing participants in the burning of the Aztecs sacred books, as these sacred books likely contained justifications, and even glorification of the Aztec's fanatic devotion to sacrificing captured enemies. Aztec accounts of great sacrifices of the past mentioned festivals in which tens of thousands of victims went to the altar. Their neighbors may have well viewed this not as religious dedication, but as a political means of draining their neighbor's manpower.

Cultural Revisionism

The Spaniards very quickly moved to break this power. The motivation for Sahugan's great "Historia de las cosas de Nueva Espana" is to give a better understanding to missionaries of Mexican religion, society and politics in order to more effectively combat it, and replace it with Christianity. It is in this light that Indian attempts to rehabilitate the image of the god Quetzalcoatl can be seen for what they are: a campaign on the part of the post-conquest Indian aristocracy to make Quetzalcoatl more palatable to the Spaniards, as most members of this aristocracy traced their descent from Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl.

To be the lineal descendent of a heart-sacrificing god-emperor might provide a convenient context for removal from power. A Quetzalcoatl who appeared to be a lost Christian saint might prove that the Aztec aristocracy were truly Christians at heart, and deserved to continue in power. It's interesting to note that the chronicler Don Alvarado de Ixlilxochtli himself was a descendent of the once all-powerful god-kings of Tezcuco in the Valley of Mexico, and was still in possession of many of the official state documents (and some of its authority) in the late 16th century, two generations after the Conquest.

The Toltecs

The Toltecs themselves were considered a legendary race of superhuman beings until relatively recently. Even Linda Schele, the great Mayanist regarded "Toltec" as being more of a claim of cultural affiliation (someone who comes from Tollan "place of reeds" ie, large city) rather than an actual nation of peoples with a capital at Tula, Hidalgo (Code of Kings, pg 200).

It is through the efforts of the early Mixtec codex painters, the early Spanish chroniclers, and the intensive field work of "glorious amateurs" such as Charnay, and modern scientific archaeologists such as Richard Diehl and Wigberto Moreno that we are able to firmly state the Myth of Quetzalcoatl does have real historical grounding in the sense that "Tollan" did indeed exist, and was situated in Tula, Hidalgo. The Toltecs were a real people, and at one point in their history they were ruled by a man who is identified as a Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl. And that these people sometime in the middle Tenth Century exerted a vast influence over a large part of Mexico, an influence which would last for the next 400 years.