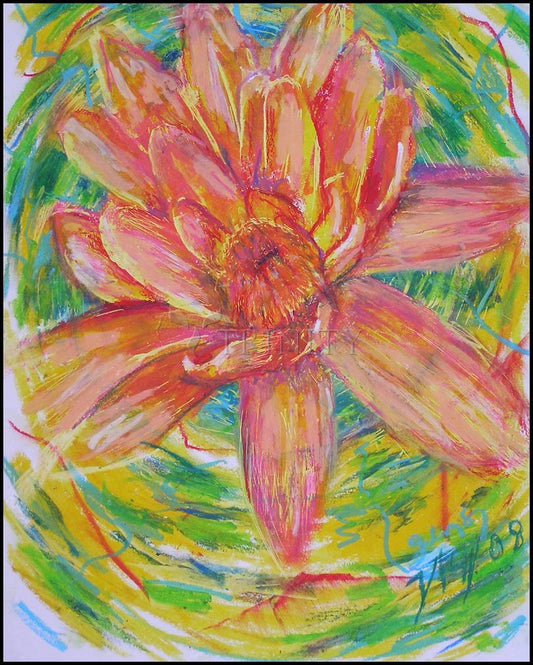

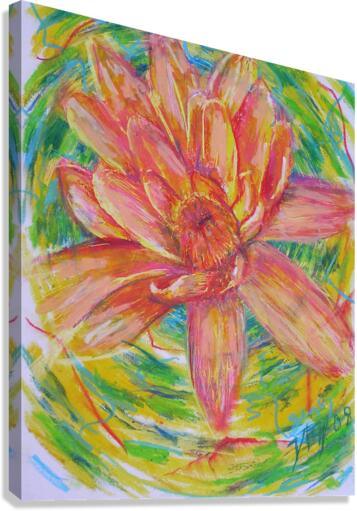

ARTIST: Fr. Bob Gilroy, SJ

ARTWORK NARRATIVE:

The water-lily pond at Monet's home in Giverny, north-west of Paris, became the principal motif of Monet's later paintings. Filling the canvas, the surface of the pond becomes a world in itself, inspiring a sense of immersion in nature. Monet's observations of the changing patterns of light on the surface of the water become almost abstract. The paintings were not fully appreciated in Monet's lifetime, and when they were reassessed in 1950s, some critics viewed them as precursors of Abstract Expressionism.

Read More

In his effort to capture just the right amount of light and dark, Monet always worked on several canvases at once and furiously followed the changing daylight. He painted intently, disregarding all the topical trends, and declared to his astonished contemporaries.

In the last decades of Monet's life, his prized water garden at Giverny became a subject the artist explored obsessively, painting it 250 times between 1900 and his death. Eventually, it was his only subject. He began construction of the water garden as soon as he moved to Giverny, petitioning local authorities to divert water from a nearby river. The resulting landscape was Monet's invention entirely, and he used it as his creative focus and inspiration.

The treatment of the water's surface, like the enveloppe of light and atmosphere that bathed the cathedrals and other serial subjects, unified the Giverny work. Here, the sky has disappeared from the painting; the lush foliage rises all the way to the horizon, and space is flattened by the decorative arch of the bridge. Our attention is focused onto the painting itself and held there, not drawn into the scene depicted. In later lily pond paintings, even more of the setting evaporates, and the water's surface alone occupies the entire canvas. Floating lily pads and mirrored reflections assume equal stature, blurring distinctions between solid objects and transitory effects of light. Monet had always been interested in reflections, seeing their fragmented forms as a natural equivalent for his own broken brushwork.

"The subject is not important to me; what I want to reproduce is what exists between the subject and me."

Near the end of his life, as a result of his intense efforts to place what he painted in the proper light and shade, he banished the subject from his paintings, bringing about the birth of abstract art.