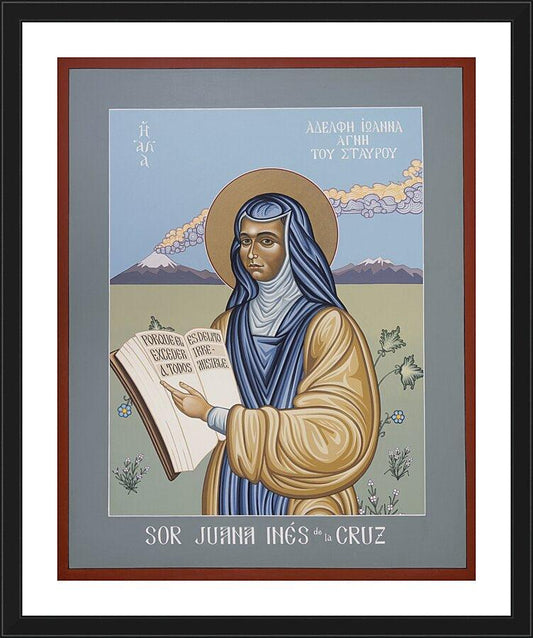

We know more about Juana Inés de La Cruz's paternal grandfather, Pedro Ramirez, than about either her father, Pedro Manuel de Asbaje, or her mother, Isabel Ramirez. Her grandfather's influence on her was profound. Using his extensive library, her grandfather taught her to read and write Latin and Spanish. Abandoned by her father, Juana was sent to live in Mexico City with a wealthy aunt after her grandfather died and her mother remarried.

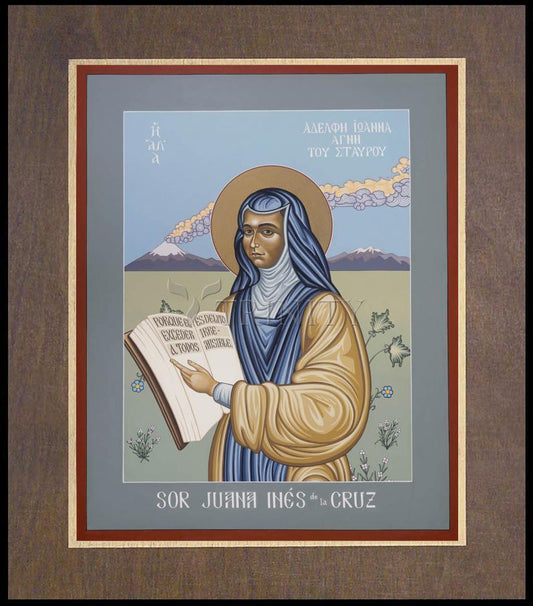

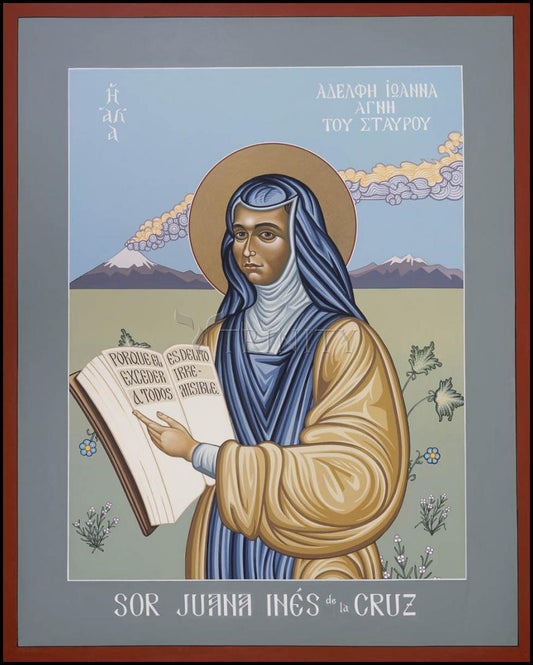

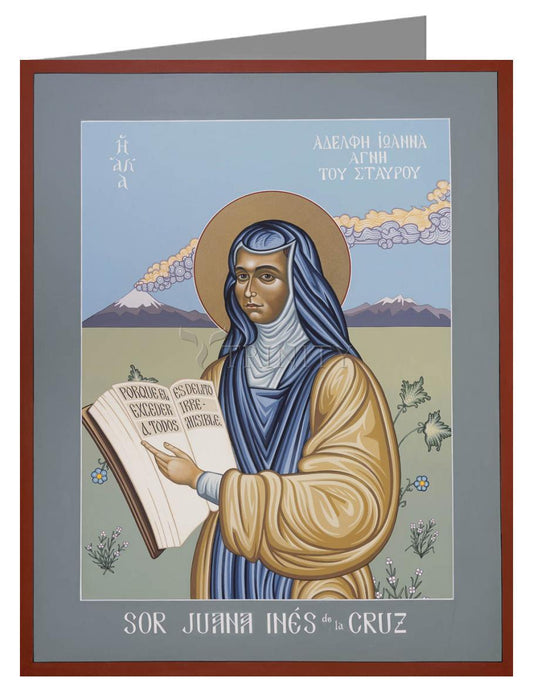

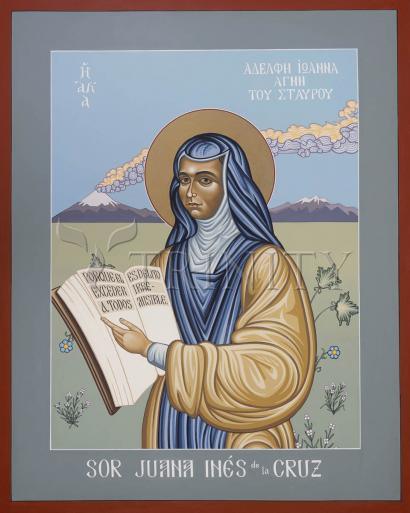

Presented to the court in 1664 when the new Viceroy and his wife arrived, the pretty, witty, intelligent, educated, teen-aged Juana quickly became a lady-in-waiting, as well as, a court favorite. Wishing to live alone to continue her studies, Juana entered the convent of the Carmelitas Descalzas (the barefoot Carmelites), a very strict order, for several months when she was 19. A year and a half later, she took her vows at the convent of San Jerónimo, an order known for its leniency.

Her convent cell, more like a modern apartment with its own sleeping room, entertaining room, kitchen, study, and bathing areas, became the intellectual center of Mexico City. (Her library allegedly contained several thousand books.) Sor Juana wrote music and poetry for the intellectual elite of the city. Visited by the Viceroy and Vicereina, she turned her cell into a salon. The Viceroy was replaced in 1672 by a priest and we know little about Sor Juana's life during his tenure. The priest was replaced in 1680 by another Viceroy and Sor Juana again became the darling of the court.

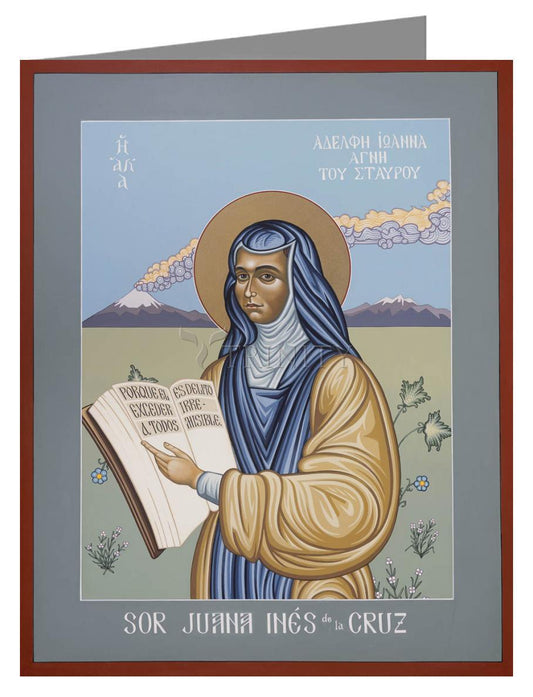

Juana strictly avoided theology until 1690 when she criticized a Jesuit priest in a private letter. During a power struggle between the Bishop of Pedula, her supporter, and the Archbishop of Mexico, the Bishop published her letter (without her permission), possibly hoping to damage one of the Archbishops supporters. In the cover letter, the Bishop admonished Sor Juana and signed himself Sor Philothea de la Cruz. The Archbishop attacked Sor Juana. Her "Reply to Sor Philothea" was an encomium defending women's biblical and theological rights to an education and the advantages which accrue to society when women are educated. Unfortunately, the Archbishop was too powerful. Sor Juana's books, musical instruments, and scientific equipment were confiscated along with many of her other possessions. And she wrote no more works for public consumption.

As was customary for her time, Sor Juana begins her reply by discounting her abilities. Indeed, in her eyes, her abilities are so limited that she could not bring herself to write on religious topics for fear of offending both the church and God himself. By restricting herself to secular topics, the most harm she could possibly do would be to bring laughter upon herself. A long biographical section follows where she explains how and why she came to her "limited education" and the hurdles she had to overcome to attain her education. She goes on to speak of the church father's writings on education for women and the biblical praise heaped on such female heroines, leaders, activists, and luminaries as Miriam, Deborah, Jael, Ester, Judith, Elizabeth, Mary, and Phoebe. She stresses the need for educated women so that new generations of women can have teachers of their own sex. She concludes by noting the accomplishments of educated, secular women, demonstrating once again the advantages of educating women.

Here is an excerpt from Reply to Sor Philothea:

Oh, how much harm would be avoided in our country if older women were as learned as Laeta and knew how to teach in the way Saint Paul and my Father Saint Jerome direct! Instead of which, if fathers wish to educate their daughters beyond what is customary, for want of trained older women and on account of the extreme negligence which has become women's sad lit, since well-educated older women are unavailable, they are obliged to bring in men teachers to give instruction in reading, writing, and arithmetic, playing musical instruments, and other skills. No little harm is done by this, as we witness every day in the pitiful examples of ill-assorted unions; from the ease of contact and the close company kept over a period of time, there easily comes about something not thought possible. As a result of this, many fathers prefer leaving their daughters in a barbaric, uncivilized state to exposing them to an evident danger such as familiarity with men breeds. All of which would be eliminated if there were older women of learning, as Saint Paul desires, and instruction were passed down from one group to another, as in the case with needlework and other traditional activities.

"Excerpts from A Sor Juana Anthology, Alan S. Trueblood, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, from Sunshne for Women