Columba, the most famous of the saints associated with Scotland, was actually an Irishman of the O'Neill or O'Donnell clan, born about the year 521 at Garton, County Donegal, in north Ireland. Of royal lineage on both sides, his father, Fedhlimidh, or Phelim, was great-grandson to Niall of the Nine Hostages, Overlord of Ireland, and connected with the Dalriada princes of southwest Scotland; his mother, Eithne, was descended from a king of Leinster. The child was baptized Colum, or Columba. In later life he was given the name of Columcille or Clumkill, that is, Colum of the Cell or Church, an appropriate title for one who became the founder of so many monastic cells and religious establishments.

As soon as he was old enough, Columba was taken from the care of his priest-guardian at Tulach-Dugblaise, or Temple Douglas, to St. Finnian's training school at Moville, at the head of Strangford lough. He was about twenty, and a deacon, when he left to study in the school of Leinster under an aged theologian and bard called Gemman. With their songs of heroes, the bards were the preservers of Irish lore, and Columba himself became a poet. Still later he attended the famous monastic school of Clonard, presided over by another Finnian, who in later times was known as the "tutor of Erin's saints." At one time three thousand students were gathered here from all over Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, and even from Gaul and Germany. It was probably at Clonard that Columba was ordained priest, although it may have been later, when he was living with his friends, Comgall, Kieran, and Kenneth, under the most gifted of all his teachers, St. Mobhi, by a ford in the river Tolca, called Dub Linn, the site of the future city of Dublin. In 543 an outbreak of plague compelled Mobhi to close his school, and Columba, now twenty-five years old and fully trained, returned to Ulster. He was a striking figure of great stature and powerful build, with a loud, melodious voice which could be heard from one hilltop to another. For the next fifteen years Columba went about Ireland preaching and founding monasteries, the chief of which were those at Derry, Durrow, and Kells.

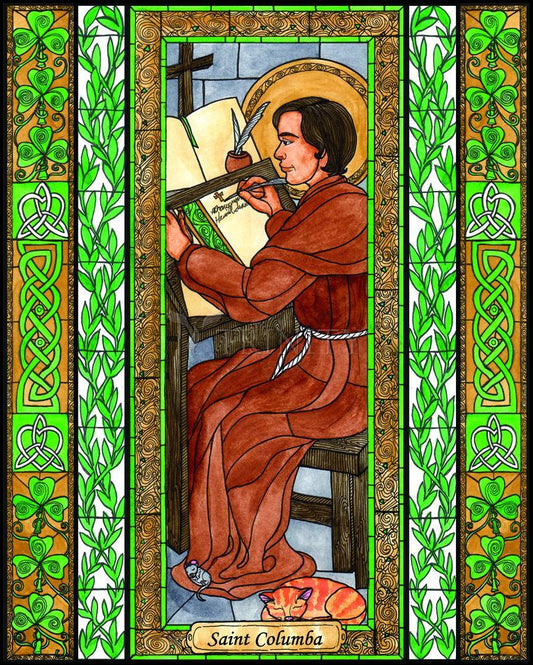

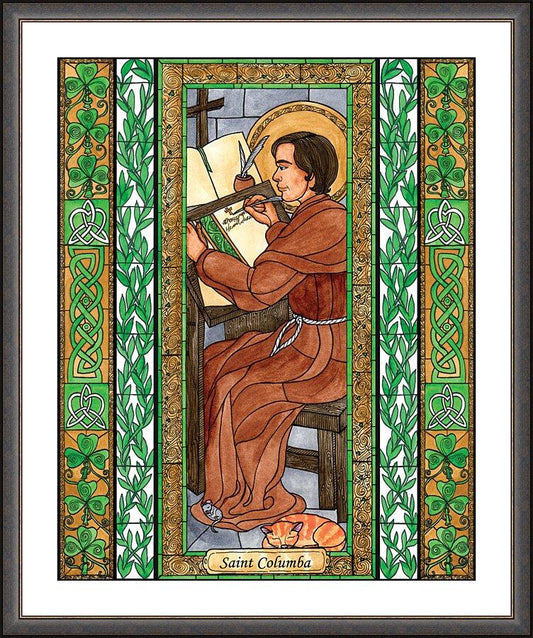

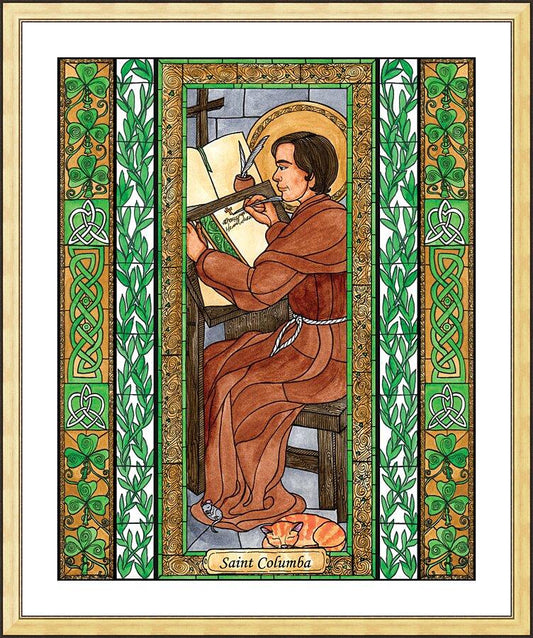

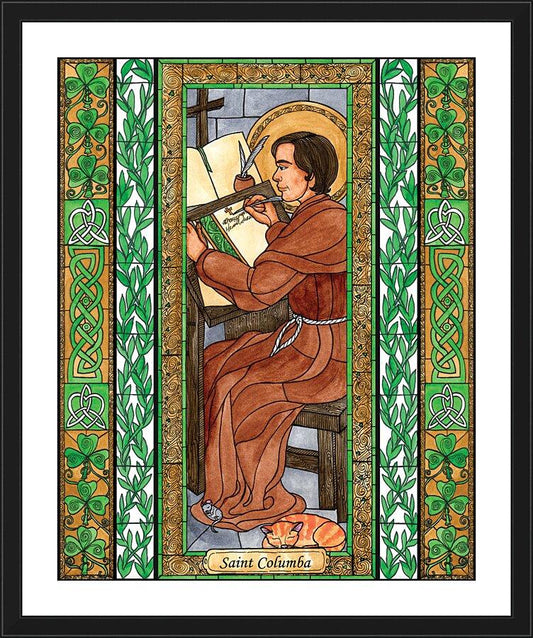

The powerful stimulus given to Irish learning by St. Patrick in the previous century was now beginning to burgeon. Columba himself dearly loved books, and spared no pains to obtain or make copies of Psalters, Bibles, and other valuable manuscripts for his monks. His former master Finnian had brought back from Rome the first copy of St. Jerome's Psalter to reach Ireland. Finnian guarded this precious volume jealously, but Columba got permission to look at it, and surreptitiously made a copy for his own use. Finnian, on being told of this, laid claim to the copy. Columba refused to give it up, and the question of ownership was put before Ring Diarmaid, Overlord of Ireland. His curious decision in this early "copyright" case went against Columba. "To every cow her calf," reasoned the King, "and to every book its son-book. Therefore, the copy you made, O Colum Cille, belongs to Finnian." Columba was soon to have a more serious grievance against the King. Prince Curnan of Connaught, who had fatally injured a rival in a hurling match and had taken refuge with Columba, was dragged from his protector's arms and slain by Diarmaid's men, in defiance of the rights of sanctuary.

The war which soon broke out between Columba's clan and the clans loyal to Diarmaid was instigated, it is said, by Columba. At the battle of Cuil Dremne his cause was victorious, but Columba was accused of being morally responsible for driving three thousand unprepared souls into eternity. A church synod was held at Tailltiu (Telltown) in County Meath, which passed a vote of censure and would have followed it by excommunication but for the intervention of St. Brendan. Columba's own conscience was uneasy, and on the advice of an aged hermit, Molaise, he resolved to expiate his offense by exiling himself and trying to win for Christ in another land as many souls as had perished in the terrible battle of Cuil Dremne.

This traditional account of the events which led to Columba's departure from Ireland may well be correct, although missionary zeal and love of Christ are the motives mentioned for his going by the earliest biographers and by Adamnan, our chief authority for his subsequent history. Whatever the impulse that prompted him, in the year 563, Columba embarked with twelve companions in a wicker coracle covered with leather, and on the eve of Pentecost landed on the island of Hi, or Iona. The first thing he did there was to erect a high stone cross; then he built a monastery, which was to be his home for the rest of his life. The island itself was made over to him by his kinsman Conall, king of the British Dalriada, who perhaps had invited him to come to Scotland in the first place. Lying across from the border country between the Picts of the north and the Scots of the south, Iona made an ideal center for missionary work. Columba seems to have first devoted himself to teaching the imperfectly instructed Christians of Dalriada, most of whom were of Irish descent, but after some two years he turned to the work of converting the Scottish Picts. With his old comrades, Comgall and Kenneth, both of them Irish Picts, he made his way through Loch Ness northward to the castle of the redoubtable King Brude, near modern Inverness. That pagan monarch had given strict orders that they were not to be admitted, but when Columba raised his arm and made the sign of the cross, it was said that bolts fell out and gates swung open, permitting the strangers to enter. Impressed by such powers, the King listened to them and ever after held Columba in high regard. As Overlord of Scotland he confirmed him in possession of Iona. We know from Adamnan that on several occasions Columba crossed the mountain chain which divides Scotland and that his travels also took him far north, and through the Western Isles. He is said to have planted churches as far east as Aberdeenshire and to have evangelized nearly the whole of the country of the Picts. When the descendants of the Dalriada kings became the rulers of Scotland, they were naturally eager to magnify the achievements of their hero and distant kinsman, Columba, and may have attributed to him victories won by others.

Columba never lost touch with Ireland. In 575 he was at the synod of Drumceatt in County Meath in company with King Conall's successor, Aidan, whom he had helped to place on the throne and had crowned at Iona, in his role as chief ecclesiastical ruler. His immense influence is shown by his veto of a proposal to abolish the order of bards and his securing for women exemption from all military service. When not on missionary journeys, Columba was to be found in his cell on Iona, where persons of all conditions visited him, some in want of spiritual or material help, some drawn by his miracles and sanctity. His biographer gives us a picture of a serene old age. His manner of life was austere; he slept on a bare slab of rock and ate barley or oat cakes, drinking only water. When he became too weak to travel, he spent long hours copying manuscripts, as he had done in his youth. On the day before his death he was at work on a Psalter, and had just traced the words, "They that love the Lord shall lack no good thing," when he paused and said, "Here I must stop; let Baithin do the rest." Baithin was his cousin. whom he had already nominated as his successor. When the monks entered the church for Matins, they found their beloved abbot lying helpless and dying before the altar. As his faithful attendant Diarmaid gently upraised him, he made a feeble effort to bless his brethren and then expired.

Iona was for centuries one of the famous centers of Christian learning. For a long time afterwards, Scotland, Ireland, and Northumbria followed the observances Columba had set for the monastic life, in distinction to those that were brought from Rome by later missionaries. His rule, based on the Eastern Rule of St. Basil, was that of many monasteries of Western Europe until superseded by the milder ordinance of St. Benedict. Adamnan, who must have been brought up on memories and recollections of Columba, writes eloquently of him: "He had the face of an angel; he was of excellent nature, polished in speech, holy in deed, great in council. He never let a single hour pass without engaging in prayer or reading or writing or some other occupation. He endured the hardships of fasting and vigils without intermission by day and night; the burden of a single one of his labors would have seemed beyond the powers of man. And, in the midst of all his toils, he appeared loving unto all, serene and holy, rejoicing in the joy of the Holy Spirit in his inmost heart."