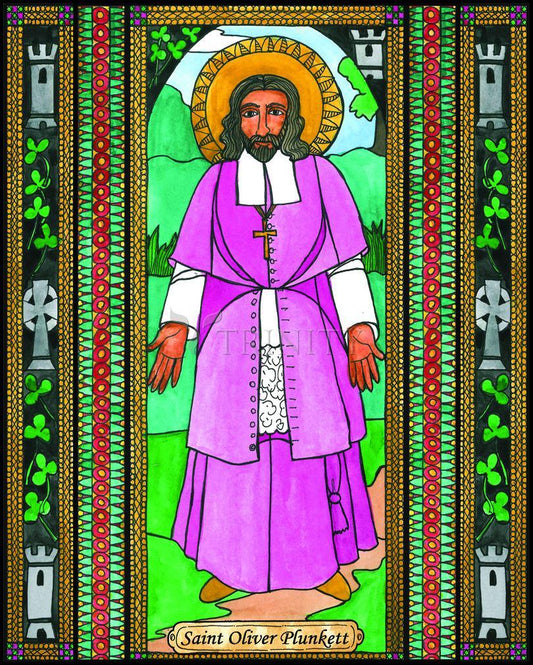

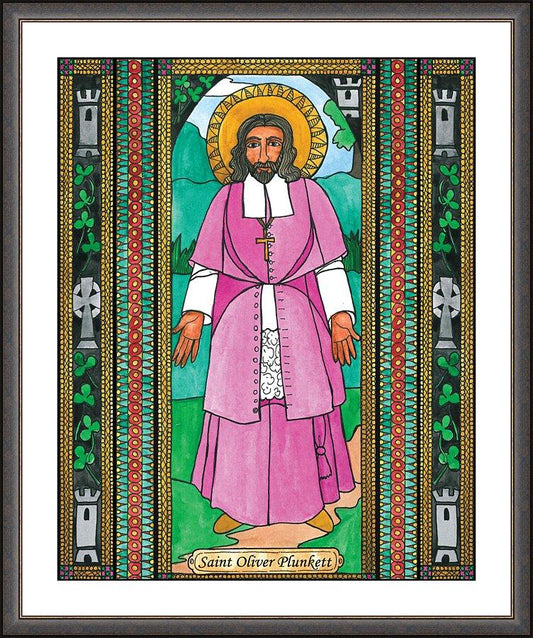

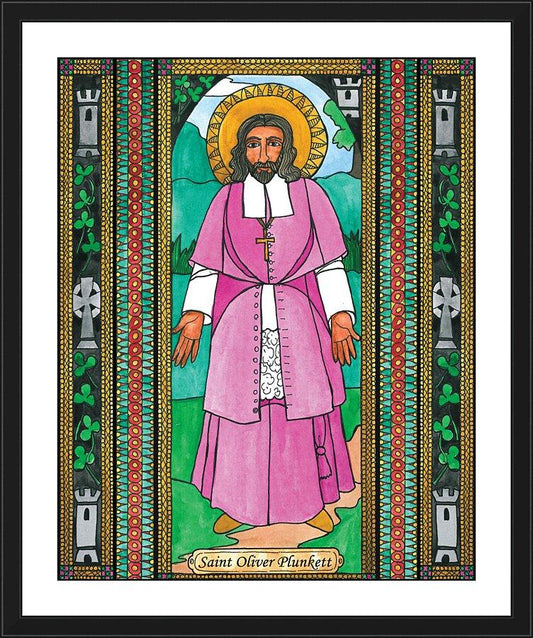

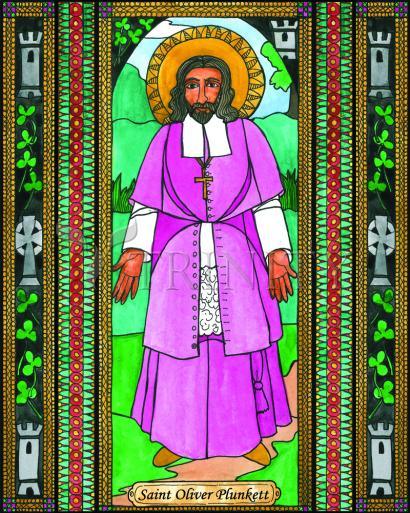

On July 1st 1681 Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland, was the last and most famous in a series of Irish martyrs executed for their faith by the English crown.

When the Roman Catholic Church canonized him on October 12th 1975, he was the first Irishman granted sainthood in almost 700 years. It was an honor that he had paid for dearly - with a perilous existence, strong civil resistance to anti-Catholic fervor and the most gruesome martyrdom imaginable.

Oliver Plunkett was born into a wealthy and influential Anglo-Norman Catholic family at Loughcrew, near Oldcastle, in County Meath on November 1st 1625. Amongst others, his family had connections with the Earls of Finglas and Roscommon, Lord Dunsany and Lord Louth. When he was 16, Oliver was sent to Rome (rather than England, where Intolerance Laws against Catholics were being passed) to continue his studies. After studying at the Irish College in Rome, Oliver was ordained in 1654.

However, due to rampant religious persecution in his homeland it was not possible for the new priest to return to Ireland and minister to his people. Instead, he spent twelve years lecturing theology at the College of Propaganda Fide. He stayed in Rome for a total of 15 years, establishing himself as an apt administrator and teacher of theology and moving comfortably up the ladder of ecclesiastical success. He seemed destined for a purposeful and serene existence in Rome. These were peaceful times in his life - the calm before the storm, so to speak.

In the meantime, the arrival of Cromwell in Ireland in 1649 had initiated the massacre and persecution of Catholics and, even though the English oppressor left the following year, his legacy was enacted in callous anti-Catholic legislation that ultimately culminated in Plunkett's shameful execution.

At the age of 44, Plunkett's then cozy life was altered forever when he was surprisingly appointed Archbishop of Armagh on January 21st 1669 (At the time there were only two bishops in Ireland and the position also carried the title Primate of All Ireland). The appointment was surprising as Plunkett was an administrator and theologian with no pastoral experience whatsoever. Nonetheless, after an absence of some 23 years, he returned to desolate Ireland the following year. The Penal Laws had been relaxed ever so slightly, allowing Catholics to publicly practice their religion, but whole populations of native Irish had been driven from their lands to the barren terrain of Connacht and it was a chaotic ministry that Oliver (who had previously petitioned to remain in Rome as outlawed Catholic priests were being hanged or shipped to the West Indies) inherited. Upon his arrival in Ireland, he wasted no time in setting up the Jesuit College (a school for boys and theology college for students) in Drogheda (which was the second city in the kingdom at the time). He extended his ministry to include gaelic-speaking Catholics of the highlands and isles of Scotland but was soon forced to conduct a covert operation due to the ongoing suppression of Catholic clergy.

On October 4th 1670, the Council of Ireland decreed that all bishops and priests must leave the country by November 20th of that year. When the Earl of Essex was appointed Viceroy of Ireland in 1672, he immediately banned Catholic education and exiled priests. Even though many senior Catholic churchmen left the country around that time, Oliver Plunkett refused to do so. Instead he travelled the nation dressed as a layman, suffering fiercely from cold and hunger, confirming people in the open countryside. However, he was eventually arrested on December 6th 1679.

Upon his arrest, the Archbishop of Armagh was detained for six weeks in Dublin Castle under false charges that he was planning to bring 20,000 French soldiers into the country and also had a mob of 70,000 Catholics under his charge who were plotting an uprising and the mass murder of Protestants and English gentry.

Plunkett's conspiracy trial was originally fixed for Dundalk but even Protestant jurors refused to convict him (on the evidence of two renegade priests, John McMoyer and Edmund Murphy). Once it became evident that Oliver Plunkett - who of course was a renowned pacifist - would never be convicted in Ireland, he was instead sent to London and locked in solitary confinement at Newgate Prison for six months pending trial. The trial, when it took place, was a pure farce and Plunkett was found guilty of high treason for "promoting the Catholic faith". Lord Chief Justice Pemberton ruled that the Irish bishop should be given a brutal death, befitting a traitor. He was drawn (two miles from Newgate Prison to Tyburn's 'triple tree'), hanged, disemboweled, quartered and beheaded. During this macabre torture, it was practice to keep the victim alive for as long as possible to ensure that the maximum punishment was exacted.

As he wasn't given enough time to bring over witnesses from Ireland, Plunkett had been unable to defend himself. The entire trial was such a blatant miscarriage of justice that even the Earl of Essex, the very man who'd had Plunkett arrested in the first place, petitioned King Charles II to pardon him before his execution, assuring the heartless sovereign of the Irishman's innocence. Even though it was wholly evident that the conviction had been in error, the King refused to intercede. The very day after Plunkett's death, the conspiracy bubble burst. The chief instigator of the persecution, Lord Shaftesbury, was consigned to the Tower at Tyburn and his principal perjured witness - a 'man' by the name of Titus Oates who first accused Catholics of the 'Popish Plot in 1678 - was thrown in gaol.

Immediately after the execution, Elizabeth Shelton, who was from a highly regarded Catholic family, succeeded in petitioning the King for the remains. Most of the venerated body is today interred at Downside Abbey, England, but the head and two forearms were saved and certified. They were entrusted to the Dominican Convent in Drogheda and are now on view, enshrined in St Peter's Catholic Church in Drogheda, along with the door of the cell Oliver Plunkett occupied at Newgate. Pilgrims from all over the world visit the Shrine of St Oliver Plunkett to venerate the relics of their glorious martyr, and many miracles have been recorded.

Oliver Plunkett is the Irish Church's most celebrated martyr and is the name most readily associated with the period of religious persecution initiated by the tyrannical Oliver Cromwell. At the Irish College in Rome, he was recognized as an exceptional student of philosophy, theology and mathematics and was widely regarded for his talent, diligence and application as well as gentleness, integrity and piety. While based in Rome throughout the period of the Cromwellian usurpation and the first years of Charles II's reign, he pleaded the cause of the suffering church in Ireland.

When he was consecrated Archbishop of Armagh, Dr Plunkett stopped off in London on his way to Ireland and spent a great deal of time trying to assuage the anti-Catholic laws in Ireland. From the time he entered his apostolate in Armagh in mid-March 1690, he was zealous in the exercise of the sacred ministry. He confirmed some 10,000 people inside the first six months and as many as 48,655 in his first four years. To bring this sacrament to the faithful, Oliver Plunkett demonstrated remarkable dedication and underwent the most severe of hardships, often living rough on little more than oaten bread and seeking out his flock on mountains and in woods to administer the sacrament. When the storm of persecution being wielded against the Irish Church erupted with renewed fury in 1673 with the result that schools were scattered and chapels closed, Plunkett refused to forsake his flock. This meant extremely tough times for Dr Plunkett and his companion, the Archbishop of Cashel, who were now wanted men and henceforth stayed in thatched huts in remote parts of the diocese.

The English Government continuously issued writs for Oliver Plunkett's arrest until he was finally captured in 1679. A host of perjured informers contrived to lie his life away. These witnesses were so notorious for their treachery that no court in Ireland would listen to them; thus the transferal of the trial to London, where Oliver was guaranteed an unfair hearing. Stories of an imminent rebellion were colorfully concocted and Plunkett's frequent visits to the Tories of Ulster were elaborately embroidered into the lies (apparently proving that he was up to something!). It was alleged that the Archbishop had chartered a foreign fleet (French or Spanish, the details were marvelously vague), which would land an army at Carlingford Bay. He was found guilty of high treason on the strength of perjured evidence from two disaffected Franciscans.

Of course, Dr Plunkett's only 'crime' was being a Catholic bishop, but the sentence of death was passed as a matter of course. Referring to Catholicism at the trial, presiding judge Chief Justice Pemberton said "there is not anything more displeasing to God or more pernicious to mankind in the world". Pemberton's performance at the trail has since been rated by Lord Brougham [in his book 'Lives of the Chief Justices of England'] as a disgrace on the English Bar.

In contrast, the dignity and grace with which Oliver Plunkett carried himself on the day of his execution was nothing short of astounding. On Friday, July 11th 1681, he was led to Tyburn for execution. The vast crowds that assembled along the way were filled with admiration for the condemned man. From the scaffold, Plunkett delivered a speech worthy of a martyr and apostle. He publicly forgave all those who were either directly or indirectly responsible for his execution. His heroism in death was a victory for his cause.

Archbishop Plunkett's name appears on the list of 264 heroic servants of God put to death because of their faith by the English in the 16th and 17th centuries. This list was officially submitted to the Holy See for approval and a Decree was signed by Pope Leo XIII in 1886 authorizing their Cause of Beatification to be submitted to the Congregation of Rites. Pope Benedict XV beatified Oliver Plunkett in 1920 and Pope Paul VI canonized him 55 years later. He was only 55 years old at the time of his unjust execution.