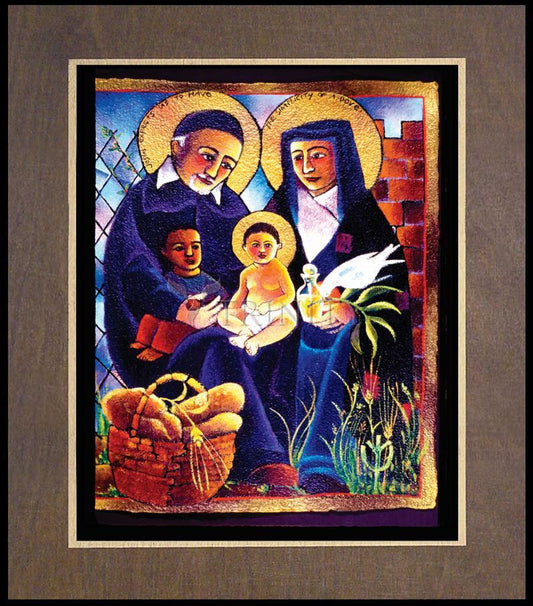

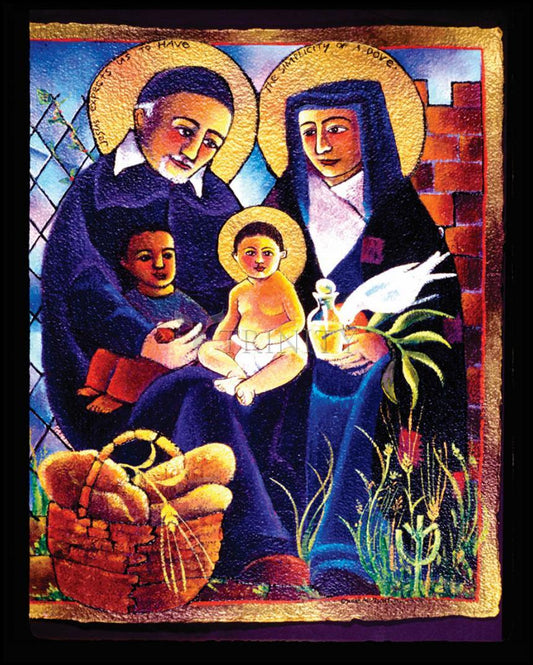

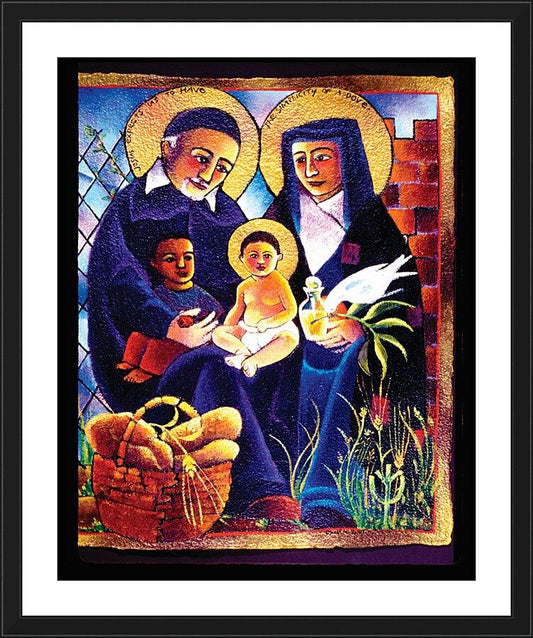

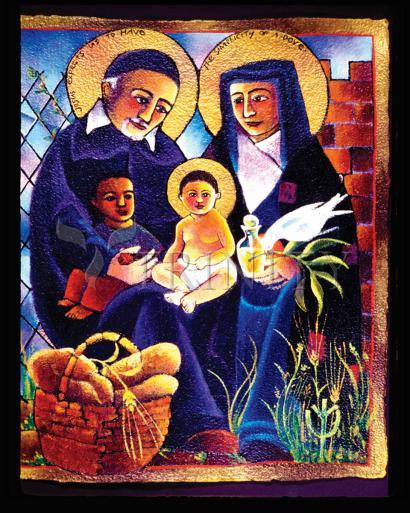

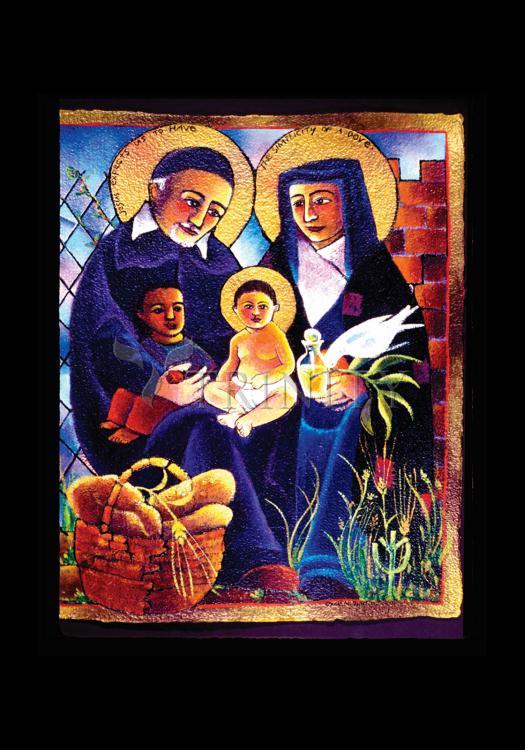

Saint Vincent served as parish priest near Paris where he started organizations to help the poor, nurse the sick, find jobs for the unemployed, etc. He was the chaplain at the court of Henry IV of France. With Louise de Marillac, he founded the Congregation of the Daughters of Charity. He instituted the Congregation of Priests of the Mission (Lazarists). Vincent worked always for the poor, the enslaved, the abandoned, the ignored, the pariahs.

Saint Louise was a woman of the highest social status. Her paternal uncle was marshal of France, another uncle was garde des sceaux. She was well educated by the Dominican nuns of Poissy after her mother's early death. Her father died when she was 15. On the advice of her confessor, Louise had decided not to join the Capuchin nuns, and in 1613, at the age of 22, she married Antoine Le Gras, secretary to Marie de Medici.

Her husband, a pious and high-minded man, allowed her to do all the good to which her kind heart prompted her in slums and in tenements of want, and protected her in those circles of society that felt outraged by her activities. After his death in 1625, she devoted herself to the education of their son, who eventually married and had children.

When she had outgrown her guardianship, she lived entirely for works of Christian charity. Louise had met St. Vincent prior to her husband's death, and he had agreed to become her confessor. He had been trying to organize devout, wealthy women to help the poor and sick in often appalling conditions. It soon became clear that many of these ladies, although well intentioned, were unfit to face the ugliness and suffering of poverty and illness. The practical work of nursing the sick in their own homes, caring for neglected children, and dealing with often rough husbands and fathers was best accomplished by women of similar social status to the principal sufferers. Louise, he realized, was made of sterner stuff.

The aristocratic ladies were better suited to the equally necessary task of fund raising and dealing with correspondence. Louise was the exception. In her Vincent saw a woman of a clear mind, great courage, endurance, and self-effacement. In 1629, in order to test his assessment, he sent Louise to make a visitation of the "Charity" of Montmirail he had founded. She passed the test and, despite unstable health, Louise made many more such

missions. Vincent chose Louise to train and organize girls and widows, mainly of the

peasant and artisan classes.

In the home Louise rented on the rue des Fossé-Saint-Victor in Paris, beginning in 1633 with four country girls, she trained groups of women for ambulatory care of the sick. Louise wanted to draw up a rule of life, but St. Vincent convinced her to wait for a sign from God. Vincent had not intended to start a religious order. The sisters, he said, should consider themselves simply as Christians devoted to the sick and poor: "your convent will be the house of the sick, your cell a hired room, your chapel the parish church, your grill the fear of God, your veil modesty."

Finally assured of Louise's dedication, Vincent permitted her to draft a rule in 1634. Essentially, this rule that was formally approved in 1655 is the rule still used today. Vows are taken only for one year and renewed. Louise made her vows in 1634, and in 1642, the first four candidates were professes as Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul in 1638. Vincent himself preferred the name, Daughters of Charity. Formal approval placed the community under Vincent and his Congregation of the Mission with Louise as their superioress until her death.

This sisterhood, according to the wishes of St. Vincent, was to realize the idea that had animated his friend, St. Francis de Sales, in creating this foundation -- the idea of an uncloistered religious community for all the evangelical tasks in the world, especially on behalf of the poor, the sick, and the little children.

St. Vincent opened an orphanage, and the sisters taught the children. They also took charge of the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris. Louise established other orphanages and hospitals, nursed plague victims herself in Paris, reformed a neglected hospital in Angers, and oversaw all the activity of the order despite her fragile health. She traveled all over France founding more than 40 daughter houses (including one in Madagascar and another in Poland) and charities.

Just before her death, she exhorted her sisters to be diligent in serving the poor "and to honor them like Christ Himself." At the time of her death the sick poor were tended in their homes in 26 Parisian parishes, hundreds of women were given shelter, and other good done. These sisters of charity accomplished immeasurable good in every part of the world through their self-sacrificing love for their fellow men.