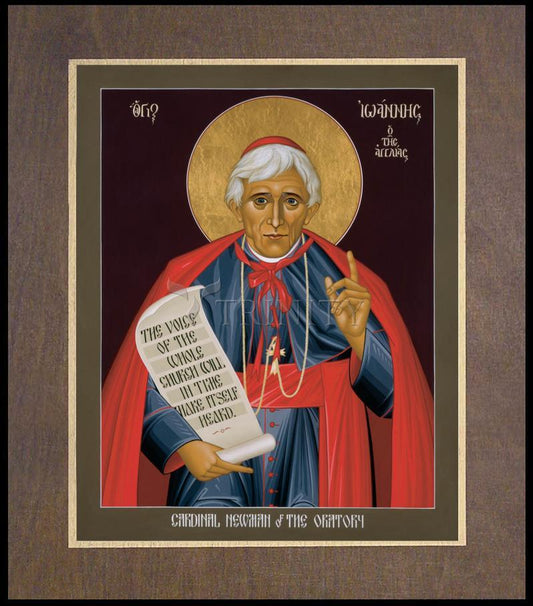

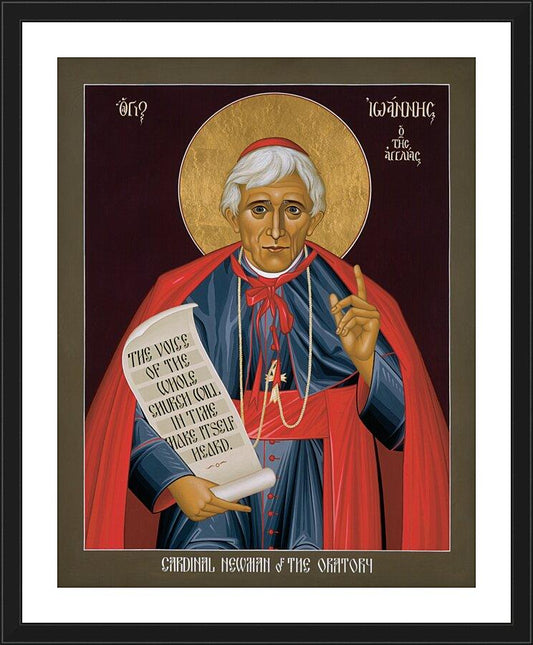

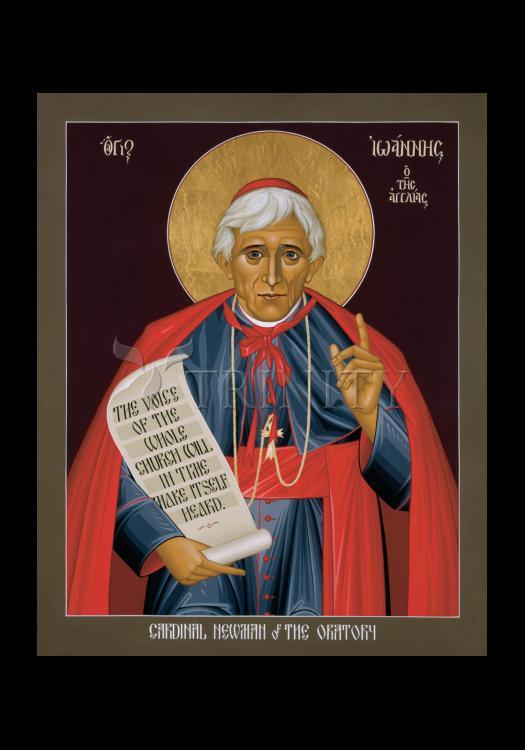

SaintJohn Henry Newman, (born Feb. 21, 1801, London, Eng."died Aug. 11, 1890, Birmingham, Warwick; beatified Sept. 19, 2010; feast day October 9), influential churchman and man of letters of the 19th century, who led the Oxford Movement in the Church of England and later became a cardinal-deacon in the Roman Catholic Church. His eloquent books, notably Parochial and Plain Sermons (1834"42), Lectures on the Prophetical Office of the Church (1837), and University Sermons (1843), revived emphasis on the dogmatic authority of the church and urged reforms of the Church of England after the pattern of the original "catholic," or universal, church of the first five centuries ad. By 1845 he came to view the Roman Catholic Church as the true modern development from the original body.

Early life and education

Newman was born in London in 1801. After pursuing his education in an evangelical home and at Trinity College, Oxford, he was made a fellow of Oriel College, Oxford, in 1822, vice principal of Alban Hall in 1825, and vicar of St. Mary's, Oxford, in 1828. Under the influence of the clergyman John Keble and Richard Hurrell Froude, Newman became a convinced high churchman (one of those who emphasized the Anglican church's continuation of the ancient Christian tradition, particularly as regards the episcopate, priesthood, and sacraments).

Association with the Oxford Movement

When the Oxford Movement began Newman was its effective organizer and intellectual leader, supplying the most acute thought produced by it. A High Church movement within the Church of England, the Oxford Movement was started at Oxford in 1833 with the object of stressing the Catholic elements in the English religious tradition and of reforming the Church of England. Newman's editing of the Tracts for the Times and his contributing of 24 tracts among them were less significant for the influence of the movement than his books, especially the Lectures on the Prophetical Office of the Church (1837), the classic statement of the Tractarian doctrine of authority; the University Sermons (1843), similarly classical for the theory of religious belief; and above all his Parochial and Plain Sermons (1834"42), which in their published form took the principles of the movement, in their best expression, into the country at large.

In 1838 and 1839 Newman was beginning to exercise far-reaching influence in the Church of England. His stress upon the dogmatic authority of the church was felt to be a much-needed reemphasis in a new liberal age. He seemed decisively to know what he stood for and where he was going, and in the quality of his personal devotion his followers found a man who practiced what he preached. Moreover, he had been endowed with the gift of writing sensitive and sometimes magical prose.

Newman was contending that the Church of England represented true catholicity and that the test of this catholicity (as against Rome upon the one side and what he termed "the popular Protestants" upon the other) lay in the teaching of the ancient and undivided church of the Fathers. From 1834 onward this middle way was beginning to be attacked on the ground that it undervalued the Reformation; and when in 1838"39 Newman and Keble published Froude's Remains, in which the Reformation was violently denounced, moderate men began to suspect their leader. Their worst fears were confirmed in 1841 by Newman's Tract 90, which, in reconciling the Thirty-nine Articles with the teaching of the ancient and undivided church, appeared to some to assert that the articles were not incompatible with the doctrines of the Council of Trent; and Newman's extreme disciple, W.G. Ward, claimed that this was indeed the consequence. Bishop Richard Bagot of Oxford requested that the tracts be suspended; and in the distress of the consequent denunciations Newman increasingly withdrew into isolation, his confidence in himself shattered and his belief in the catholicity of the English church weakening. He moved out of Oxford to his chapelry of Littlemore, where he gathered a few of his intimate disciples and established a quasi-monastery.