El Salvador: 'A blindness of conscience'

"To threaten those who are part of civil organizations in society and human rights activists, who care about the problems of those in most need for justice in this country, shows nothing but a blindness of conscience, which does not allow them to see how much we need in this country the respect for human rights, as a foundation for the rule of law and peace."

Oficina de Tutela Legal del Arzobispado, 28 June 1996

A fierce civil war raged in El Salvador during the 1980s and early 1990s between government forces and the armed opposition Farabundo Martà National Liberation Front (FMLN). People from all sectors of society suspected of opposing the government became victims of human rights violations, including arbitrary arrest, torture, "disappearance" and extra judicial executions. Human rights defenders paid a high price for their legitimate activities exposing government abuse during the war. Moreover, those responsible for these violations have not been punished for their hideous crimes.

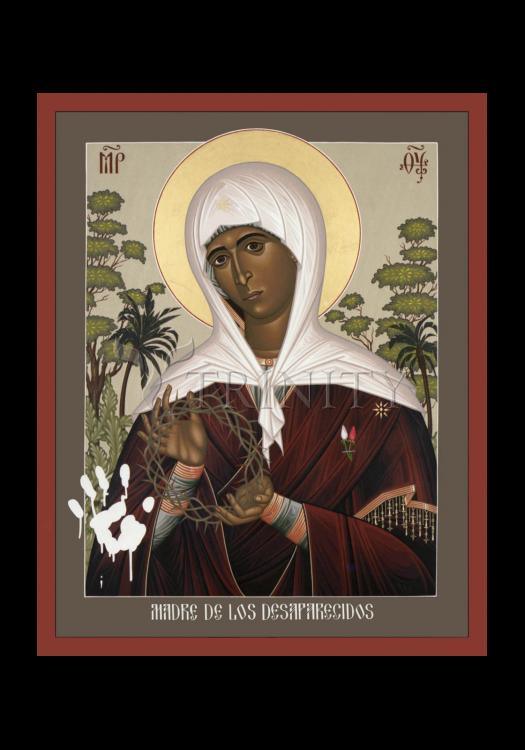

One of the best known martyrs for the human rights cause is Monsignor Oscar Arnulfo Romero y Galdámez, Archbishop of San Salvador. He was assassinated while celebrating mass on 24 March 1980 in the chapel of the Divine Providence Hospital, San Salvador. He had become an outspoken critic of human rights violations and a leading human rights defender. In March 1980 he wrote to the then President of the United States of America, Jimmy Carter, asking the USA not to provide military assistance to El Salvador which might be used to perpetrate human rights violations. He was killed shortly afterwards.

The killing of Archbishop Romero was investigated by the Commission on the Truth for El Salvador (Truth Commission), established under the 1992 Peace Agreements between the Government of El Salvador and the FMLN. In its 1993 report the Commission concluded that:

There is full evidence that:

Former Major Roberto D'Aubuisson gave the order to assassinate the Archbishop and gave precise instructions to members of his security service, acting as a "death squad", to organize and supervise the assassination."

and that

"There is full evidence that the Supreme Court played an active role in preventing the extradition of former Captain Saravia (actively involved with others in planning and carrying out the assassination) from the United States and his subsequent imprisonment in El Salvador. In so doing, it ensured, inter alia, impunity for those who planned the assassination."

No has been brought to justice for the killing of Archbishop Romero.

In January 1992 the government and the FMLN signed a definitive peace accord in Mexico City after negotiations mediated by the UN. On 15 December 1992 the armed conflict was formally ended. However, human rights defenders continue today to be the targets of attacks, although on a reduced scale, for their efforts to protect and promote fundamental rights and freedoms.

Targeting CDHES:

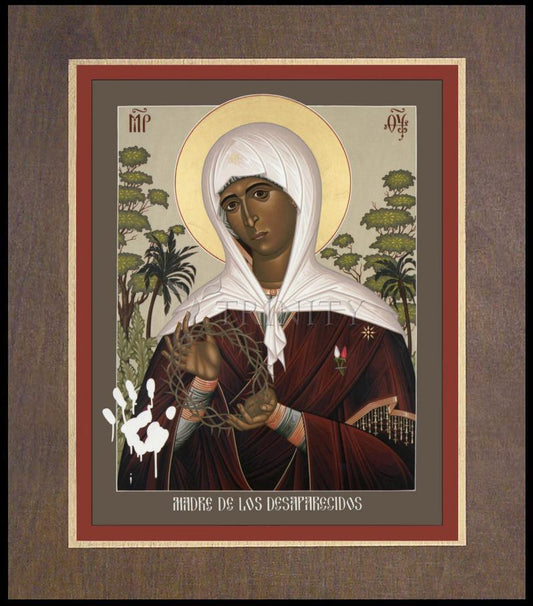

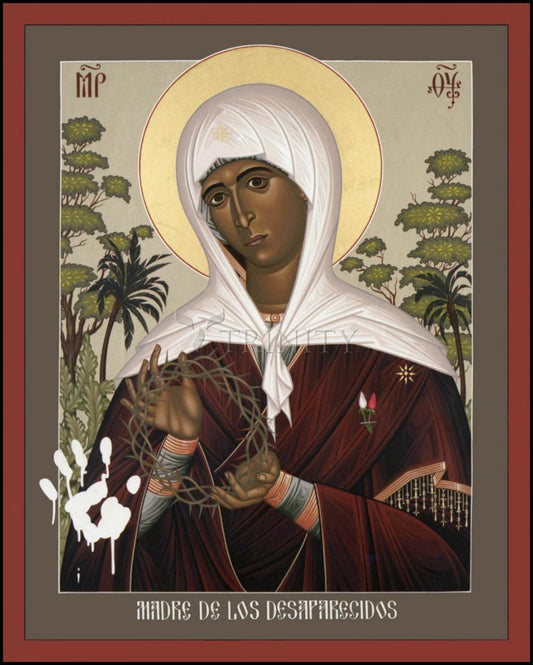

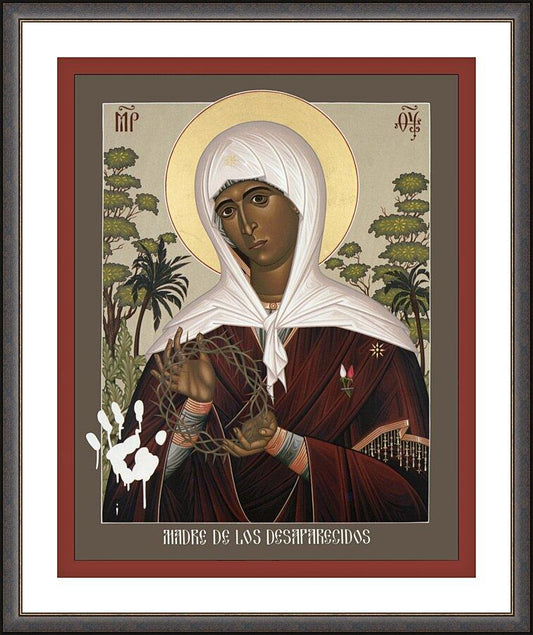

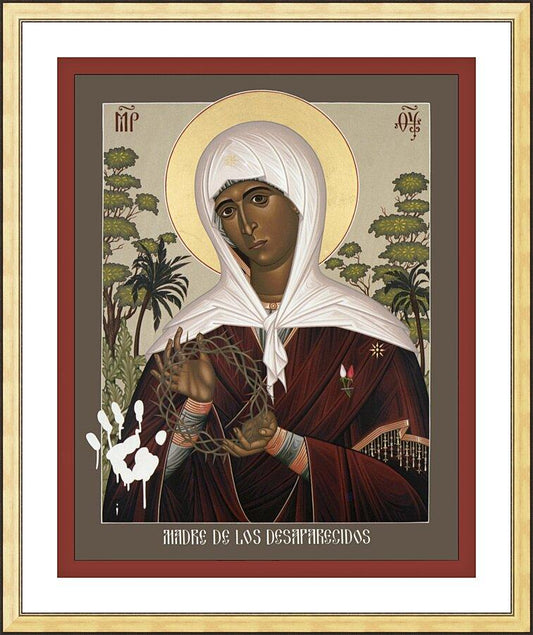

Part of the legacy left by Archbishop Romero was the Commission on Human Rights of El Salvador (CDHES) which he helped create. The CDHES was founded on 1 April 1978 by a group of university students and professionals with the aim of promoting and defending respect for human rights. It has been a target of repression ever since and has paid dearly for its efforts. Several of its members have been killed or "disappeared" as a result of their commitment and work on behalf of victims of human rights violations.

MarÃa Magdalena HenrÃquez, Press Coordinator of CDHES, was kidnapped on 3 October 1980 in San Salvador, the capital city, by police officers in civilian clothes. Her body was found a few days later in a shallow grave outside the capital. She had been particularly active in submitting writs of habeas corpus on behalf of "disappeared" people. Ramón Valladares, CDHES Administrator, was murdered on 25 October 1980 by unidentified men.

On 14 March 1983 CDHES President Marianella GarcÃa Villas was killed by members of the armed forces. There were different versions about the events which led to her death, ranging from claims that she was among the victims in a massacre carried out by the "Atlacatl" Battalion of Rapid Reaction, in La Bermuda, department of Cuscatlán, to allegations that she had been murdered after being tortured for several hours by the military, to the government version that she had been killed in a confrontation with the army.

Marianella GarcÃa Villas had been detained by the authorities and had left El Salvador at the end of 1981 after her name was included twice in lists of "traitors." One of the lists was published by the Press Committee of the Armed Forces and another was issued by the Maximiliano Hernández Brigade, a far-right paramilitary group. These lists effectively gave official sanction to groups carrying out extra judicial executions. She had returned to investigate reports of indiscriminate bombing of unarmed civilians and the use of chemical weapons against civilians.

Major Roberto D'Aubuisson, who founded the right-wing Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) in 1981, had publicly referred to Marianella GarcÃa Villas as "Comandante LucÃa" and the government portrayed her as a guerrilla who had been terrorizing peasants when she was killed. Despite national and international calls for a thorough and independent investigation of her death those responsible have never been brought to justice.

Herbert Ernesto Anaya Sanabria was the Coordinator of the CDHES when he was murdered on 26 October 1987. He was shot by men in plain clothes; he had been previously subjected to repeated harassment and threats, directed at him and other independent human rights defenders in El Salvador and had been acquitted of charges of collaboration with the armed opposition, in February 1987.

The Truth Commission, mandated under the peace accords to investigate "exceptionally important acts of violence" committed by the government or FMLN forces since 1980, found that the authorities had failed to protect human rights according to its international commitments, to properly investigate the murder of Herbert Anaya and to bring those responsible for his death to trial.

Attacks on other human rights defenders:

Even after the end of the civil war in El Salvador brought a reduction in the number of human rights violations, defenders have continued to be targets of threats, attacks or intimidation. On 19 May 1994 the offices shared by the Salvadorean Women's Movement (MSM) and the Madeleine Lagadec Human Rights Centre were broken into.

The following day Alexander Rodas Abarca was killed by unidentified gunmen as he was guarding the offices. He was a reserve member of the National Police and member of the security group for the Revolutionary Party of Central American Workers (PRTC), a faction of the FMLN, which became a political party under the terms of the 1992 peace accords. The directors of the two organizations dismissed robbery as the motive for the break-in since nothing of any value was taken. They said, however, that the staff of the office had seen people and vehicles watching the premises for some days before the incident.

Dr. Francisco Carrillo, director of the non-governmental organization FUNDASIDA, and other members of the organization were the targets of death threats and their offices were raided in June 1995. FUNDASIDA works on behalf of people with AIDS. The three men involved said they were looking for Dr Carrillo (who was not there at the time). They left a message with those present that "he owes us something and we are going to kill him." Two days later the receptionist was reported to have received an anonymous phone call, in which the caller asked her: "Do you want to die?... then prepare yourselves, today at 3pm."

On 6 July 1995 Amnesty International learned that the gay men's group Among Friends had received three death threats by telephone from a "death squad", saying they would come to their next meeting and kill everyone. In October and November 1994 Wilfredo Valencia Palacios, Deputy Director of the Oscar Romero AIDS Project, was threatened with death in the street by unidentified armed men, believed to belong to a "death squad."

In early October 1995 Lic BenjamÃn Cuéllar MartÃnez, director of the Central American University's Institute of Human Rights (IDHUCA), and Lic Luis Romero GarcÃa Alemán, director of CDHES, were attacked by unknown men. They had just participated in an event commemorating the killing of six Jesuit priests, their cook and her daughter in November 1989. According to reports the unidentified armed men entered the IDHUCA building and forced the two men to go to the director's office. Once there they disconnected telephones and computers and searched the offices while continuously threatening the two victims, who had been gagged. They left when others in the building raised the alarm.

On 17 February 1996 unidentified men raided the premises of the Committee of Relatives of Victims of Human Rights Violations in El Salvador (CODEFAM). Nothing of value was taken.

CODEFAM was founded in 1981, to defend human rights, to provide legal and social assistance to victims and their families and to work for the release of political prisoners and for the "disappeared." Since the signing of the 1992 peace accords CODEFAM has continued to work for the promotion and defense of civil, economic, social and political rights.

Human rights defenders continue to appear on "death lists" in El Salvador. On 26 June 1996 a group calling itself the Roberto d'Aubuisson Nationalist Force (FURODA) emerged. In its first public statement FURODA issued threats against 15 people. Those on the list included: Monsignor Gregorio Rosa Chávez, Auxiliary Bishop of San Salvador; Medardo Gómez, Lutheran Bishop; and Dra Victoria Marina Velásquez de Avilés, National Human Rights Procurator. They have been involved in human rights work and have publicly expressed their commitment to human rights and democracy.

The statement referred to them as "worms" and warned: "Your days are numbered." The group's threats said, among other things: "We want to tell you that from this moment on we have prepared the conditions to punish in an exemplary way all those who attempt to abort the democratic process in El Salvador. Therefore, (those named above) are now considered as targets of FURODA." It went on to say that (those listed) "will receive a just payment for defending the terrorists who, from the University of El Salvador, continue acting as instruments to destabilize El Salvador."

Monsignor Rosa Chávez had received such threats before, on 10 June 1994, from a caller who identified himself as a member of the Comando Domingo Monterrosa (named after a military official killed in the 1980s).

Amnesty International is concerned by the failure of the authorities to take effective measures against the so-called "death squads" (which have committed numerous violations against human rights defenders, among others) and any other groups or individuals who reportedly continue violating human rights. For the process towards full democracy and respect for human rights outlined in the peace accords, the report of the Truth Commission and the Joint Group (set up to investigate "death squads") to become a reality, the government must show that it has the political will and the institutional capacity to fulfill its promises. The alternative could be a slide back towards the practices of widespread human rights violations of the past.

Amnesty International: CENTRAL AMERICA and MEXICO - Human rights

UN TRUTH COMMISSION ON SALVADORAN DEATH SQUADS

In its final report, the U.N.-sponsored Truth Commission investigating human rights abuses presented a detailed history of the death squads. Excerpts from the report are presented below.

El Salvador has a long history of violence committed by groups that are neither part of the Government nor ordinary criminals. For decades, it has been a fragmented society with a weak system of justice and a tradition of impunity for officials and members of the most powerful families who commit abuses.

Violence has formed part of the exercise of official authority, directly guided by State officials. This has been reflected, throughout the country's history, in a pattern of conduct by the government and power elites of using violence as a means to control civilian society. In the past 150 years, a number of uprisings by peasants and indigenous groups have been violently suppressed by the State and by civilian groups armed by landowners.

A kind of complicity developed between businessmen and landowners, who entered into a close relationship with the army and intelligence and security forces. The aim was to ferret out alleged foreign conspiracy.

There were several stages in the process of formation of the death squads in this century. The National Guard was created and organized in 1910 and the following years. From its inception, members cooperated actively with large landowners, at times going so far as to crack down brutally on the peasant leagues and other rural groups that threatened their interests.

Local National Guard commanders "offered their services" or hired out guardsmen to protect landowners' material interests. The practice of using the services of "paramilitary personnel", chosen and armed by the army or the large landowners, began soon afterwards.

In other words, from virtually the beginning of the century, a Salvadoran State security force, through a misperception of its true function, was directed against the bulk of the civilian population. In 1932, National Guard members, the army and paramilitary groups, with the collaboration of local landowners, carried out a massacre known as "La Matanza", in which they murdered at least 10,000 peasants in the western part of the country in order to put down a rural insurrection.

Between 1967 and 1979, General Jose Alberto Medrano, who headed the National Guard, organized the paramilitary group known as ORDEN. The function of this organization was to identify and eliminate alleged communists among the rural population. He also organized the national military intelligence agency, ANSESAL. These institutions helped consolidate an era of military hegemony in El Salvador, sowing terror selectively among alleged subversives identified by the intelligence services.

The reformist coup by young military officers in 1979 ushered in a new period of intense violence. Various circles in the armed forces and the private sector vied for control of the repressive apparatus. Hundreds and even thousands of people perceived as supporters or active members of a growing guerrilla movement... were murdered. Members of the army, the Treasury Police, the National Guard, and the National Police formed "squads" to do away with enemies. Private and semi-official groups also set up their own squads or linked up with existing structures within the armed forces.

It should be said that, while it is possible to differentiate the armed forces death squads from the civilian death squads, the borderline between the two was often blurred. For instance, even the quads that were not organized as part of any State structure were often supported or tolerated by State institutions. Frequently, death squads operated in coordination with the armed forces and acted as a support structure for their activities. The clandestine nature of these activities made it possible to conceal the State's responsibility for them and created an atmosphere of complete impunity for the murderers who worked in the squads.

The 1979 coup d'etat altered the political landscape in El Salvador. One of the competing factions directly affected by the coup was a core of military officers who sought to pre-empt the groups that had staged the coup and also any reform movement. The leader of this faction was former Major Roberto D'Aubuisson, who up until 1979 had been third in command of ANSESAL.

Former Major D'Aubuisson drew considerable support from wealthy civilians who feared that their interests would be affected by the reform programs announced by the Government Junta. The Commission on the Truth obtained testimony from many sources that some of the richest landowners and businessmen inside and outside the country offered their estates, homes, vehicles and bodyguards to help the death squads. They also used their funds to organize and maintain the squads, especially those directed by former Major D'Aubuisson.

After the assassination of Monsignor Romero, which, in very closed circles, D'Aubuisson took credit for having planned, his prestige and influence grew among the groups that wielded economic power, gaining him further support and resources.

It must be pointed out that the United States Government tolerated, and apparently paid little official heed to the activities of Salvadoran exiles living in Miami. This group of exiles directly financed and indirectly helped run certain death squads.

—Excerpts from pages 132-137 of the Truth Commission report