When Father Solanus Casey died in Detroit in 1957, all he left after 86 years on this earth were a small crucifix, an old pair of sandals, several religious pictures, a wooden statue of St. Anthony, some dog-eared religious books, a knot of heavily darned socks and a framed, 40-year-old picture of his family.

But he left another rich legacy -- a long list of curious "favors" to an equally long list of devoted believers.

Father Solanus Casey had come to Detroit to be a Capuchin friar. During his years as a priest he spent time in other states, but he began and ended his career in Detroit.

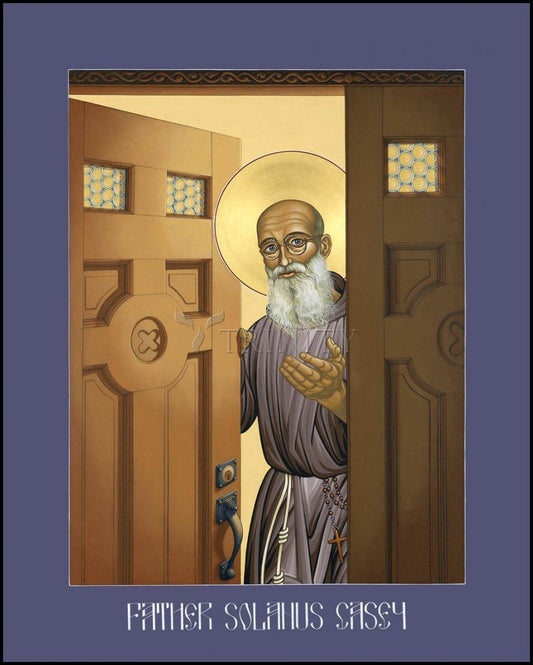

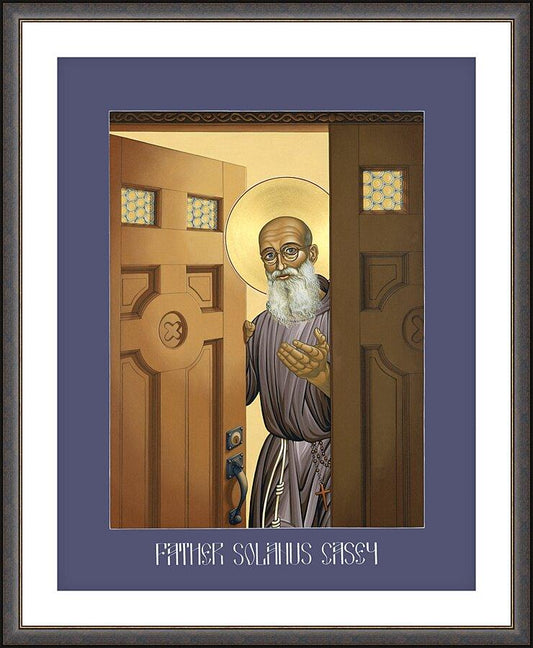

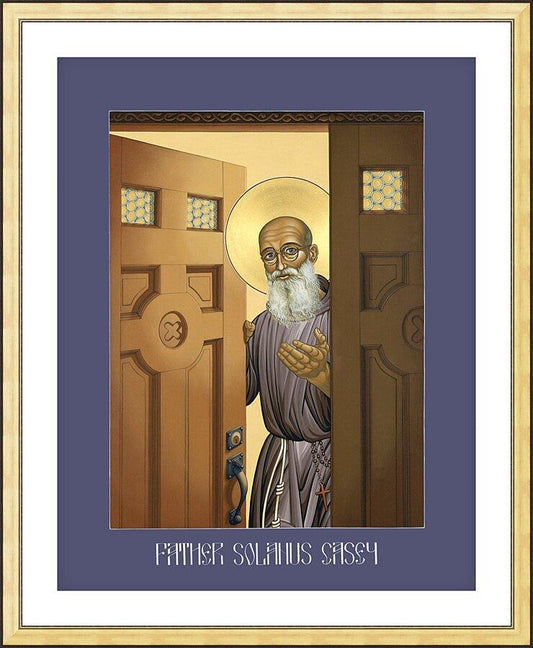

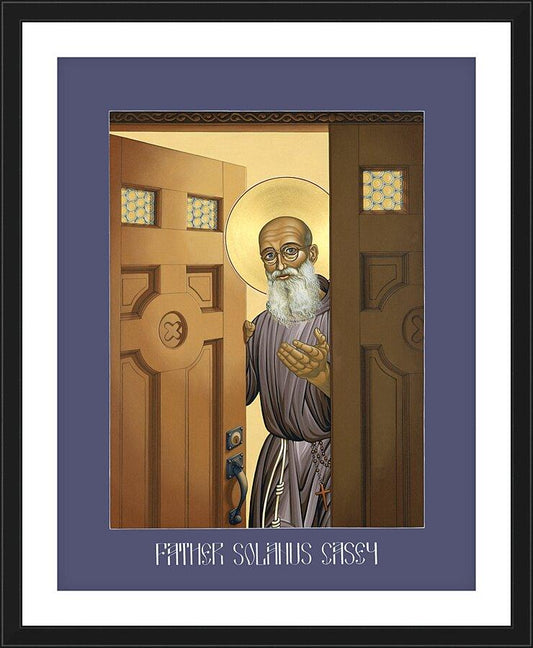

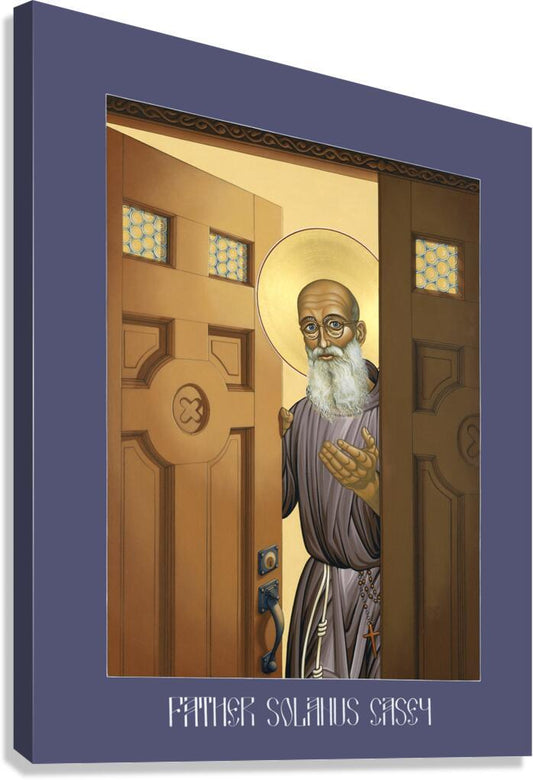

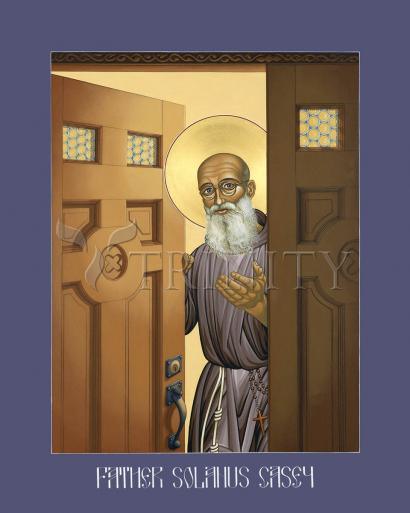

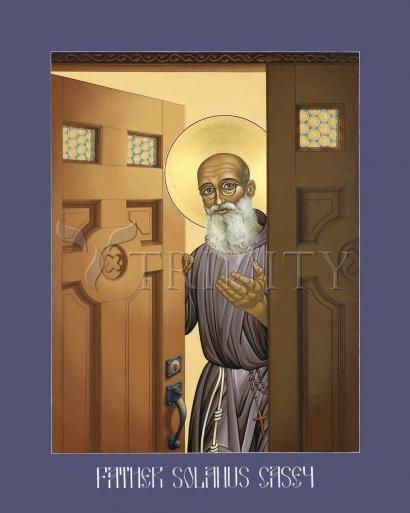

The thin, bald ascetic with horn-rimmed spectacles and a flowing gray beard spent 23 years at St. Bonaventure Monastery in Detroit. He was a man of rare holiness. A mystic.

Barney Casey was the oldest of 16 children of an Irish-American family from Superior, Wisconsin. He'd already been a lumberjack, a prison guard, and a streetcar motorman. One day while driving the streetcar through a tough section of Superior, he came upon a drunken sailor stabbing a young woman.

"The scene remained with him," wrote his biographer, James P. Derum. "To him the brutal stabbing and the sailor's hysterical cursing symbolized the world's sin and hate and man-made misery.

"He saw...that the only cure for mankind's crime and wretchedness was the love that can be learned only from and through Him who died to show men what love is."

Barney believed the Lord wished him to dedicate his life to Him and he decided to study for the priesthood. But he was having troubles academically. Then he planned a novena, prayers to Mary in preparation for her Dec. 8 feast of the Immaculate Conception. He became aware of the Blessed Virgin's presence: "Go to Detroit," he distinctly heard her say.

Lugging a trunk, he went to Detroit.

In 1897 he took the name of St. Francis Solanus, a 17th century Spanish nobleman, intellectual, missionary and preacher. Six years later he was ordained.

Because he ranked only in the lower half of his class, his teachers recommended that his priestly office be severely restricted. He could say mass but was not permitted to expound from the pulpit on dogma. He was not allowed to hear confessions except under emergency circumstances.

He spent some time in New York, in Yonkers and in Harlem. Here began the series of inexplicable events that were to be linked to him for the next 36 years.

Father Solanus began promoting a prayer group, the Seraphic Mass Association, in which all members had access to the prayers of the entire group. He offered to help those in distress to fill out the prayer group's application card and in doing so he would listen to their problems.

Unexpectedly quick recoveries and remarkable solutions to their problems shocked and delighted the petitioners and the word spread. Father Solanus suddenly found himself very busy and his superior, Father Provincial Benno Aichinger, directed him to keep a record of these "special favors."

Father Solanus returned to Detroit in 1924, 28 years after first arriving as a novice. He stayed as doorkeeper until 1945, the year before he retired.

During his 21 years as porter at St. Bonaventure, he filled seven notebooks with more than 6,000 requests for help from petitioners. And to some 700 of these he recorded reported cures from cancer, leukemia, tuberculosis, diphtheria, arthritis, blindness, and other maladies. These brief postscripts also report conversions of fallen-away churchgoers and favorable resolutions of domestic and business problems.

Not all the requests were granted. Gertrude Brennan complained about a minor sinus problem to the priest. At the time he was in the yard of the monastery swatting flies with a fly swatter. He continued swatting during her complaint. She took his actions to mean that some minor annoyances were merely that.

His humility never allowed him any embarrassment when a sinner asked him to hear a confession and Father Solanus had to call for another priest to be the confessor. It did, however, bother a young friar who often was called. But eventually the friar came to see that Father Solanus wasn't bothered by his "lower rank." He simply accepted what God had allowed for him.

But his humility did not protect the other priests and brothers from his singing in a high squeaky voice while playing the violin. An ill friar once told a visitor to quickly turn on the radio because Father Solanus had just gone to get his violin to try to cheer the invalid, and he hoped the radio would discourage him.

The long list of favors granted included one to the Chevrolet motor company. In 1925 the firm was near bankruptcy when an auto worker, John McKenna, who feared losing his job, enrolled Chevrolet into the Seraphic Mass Association for 50 cents. Two nights later the company got an order for 45,000 machines.

During the Great Depression, the number of daily patrons of the monastery's soup kitchen tripled and Father Solanus joined the expanded efforts. Arthur Rutledge came to Solanus with a stomach tumor. Solanus told him go back to the doctor and check again, then come and help in the soup kitchen. The doctor found that the tumor was gone and the kitchen had a new volunteer.

But Solanus' was not the ideal fund-raiser. Once he went to a bar for a beer with a kitchen worker. The bar owner handed him a check for the soup kitchen, but Father Solanus said, "Oh I didn't come here for that; I came for a beer. You have a very good beer and you have a nice place here."

Suffering from overwork, Solanus was sent to Brooklyn in 1945 and later to a farm area in Huntington, Indiana, where he received about 200 letters a day. He tried to answer the letters, but in his 80s and suffering with arthritis, the friars had a rubber stamp made of his signature.

Again and again, in his letters, he repeated his life's message--that confidence in God is the very soul of prayer and becomes the condition for supernatural intervention in our lives. "God condescends to use our powers if we don't spoil his plans by ours," he frequently wrote.

In January 1956, diagnosed with skin cancer, his superiors decided to send him back to Detroit to be near expert medical care. His contact with petitioners was restricted.

A novice recalled that on the last Christmas evening before the death of Father Solanus, he overheard the friar playing his violin alone in the chapel, singing Christmas carols to the Christ Child.

Father Solanus died July 31, 1957, on the 53rd anniversary of his first Mass.

After his death, Clare Ryan, a former Detroiter, started the Father Solanus Guild. Mrs. Ryan believed that Father Solanus cured her on two occasions: of stomach cancer in the 1930s; and 20 years later, of paralysis of the legs.

In the 1950s her legs began to swell, and doctors told her that she would be in a wheelchair soon. She consulted Father Solanus.

"Stand up," he said. "Then he slapped both my legs and said to them, 'Stand up and do your job.'

By 1964 the local group had grown to about 3,500 members nationally. They wanted some action toward his canonization. In 1974 Brother Leo Wollenweber started gathering the evidence and filled two big, gray filing cabinets.

TV programs told of Father Solanus, and in 1994, "Unsolved Mysteries" had a show about his "mysteries."

Finally, after 30 years, Pope John Paul II approved the reading of the decree declaring the heroic virtues of Casey. This gives him the title "Venerable," the first of three steps in the rigorous process toward canonization. If he becomes sainted, he will be the first American-born man thus honored. Elizabeth Ann Seton was canonized in 1976.

Father Solanus was buried in a small plot on the monastery grounds. Later, in 1987, his body was exhumed, given a new robe, and placed inside the St. Bonaventure chapel in a crypt. Today thousands of members of the Father Solanus Guild and others carry around as relics threads from his brown habit in decoratively crocheted badges.

(Information gathered from The Detroit News files and from a booklet by Boniface Hanley, OFM)

—Excerpts from Father Solanus Casey and his 'favors' by Vivian M. Baulch