Guadalupe is, strictly speaking, the name of a picture, but the name was extended to the church containing the picture and to the town that grew up around the church. It makes the shrine, it occasions the devotion, it illustrates Our Lady. It is taken as representing the Immaculate Conception, being the lone figure of the woman with the sun, moon, and star accompaniments of the great apocalyptic sign with a supporting angel under the crescent. The word is Spanish Arabic, but in Mexico it may represent certain Aztec sounds. Its tradition is long-standing and constant, and in sources both oral and written, Indian and Spanish, the account is unwavering. The Blessed Virgin appeared on Saturday, 9 December to a 55 year old neophyte named Juan Diego, who was hurrying down Tepeyac hill to hear Mass in Mexico City. She sent him to Bishop Zumarraga to have a temple built where she stood. She was at the same place that evening and Sunday evening to get the bishop's answer. The bishop did not immediately believed the messenger, had him cross-examined and watched, and he finally told him to ask the lady who said she was the mother of the true God for a sign. The neophyte agreed readily to ask for sign desired, and the bishop released him. Juan was occupied all Monday with Bernardino, an uncle, who was dying of fever. Indian medicine had failed, and Bernardino seemed at death's door. At daybreak on Tuesday 12 December 1531, Juan ran to nearby St. James's convent for a priest. To avoid the apparition and the untimely message to the bishop, he slipped round where the well chapel now stands. But the Blessed Virgin crossed down to meet him and said, "What road is this thou takest son?" A tender dialogue ensued. She reassured Juan about his uncle, to whom she also briefly appeared and instantly cured.

Calling herself Holy Mary of Guadalupe she told Juan to return to the bishop. He asked for the sign he required. Mary told him to go to the rocks and gather roses. Juan knew it was neither the time nor the place for roses, but he went and found them. Gathering many into the lap of his tilma, a long cloak or wrapper used by Mexican Indians, he came back. The Holy Mother rearranged the roses, and told him to keep them untouched and unseen until he reached the bishop.

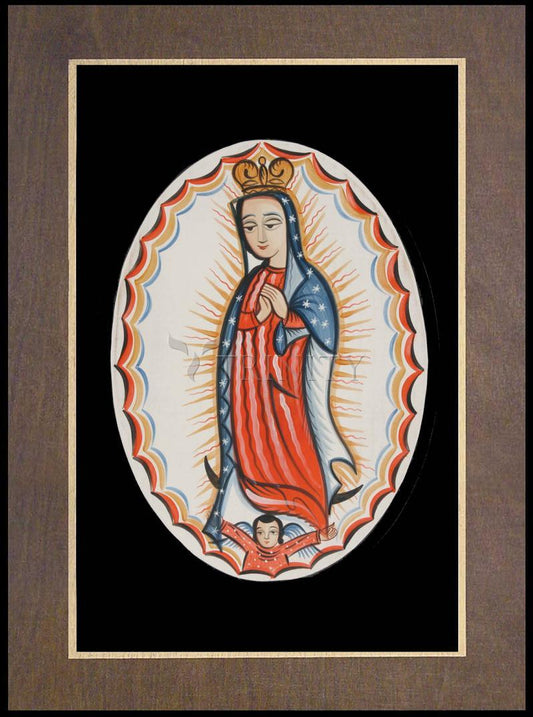

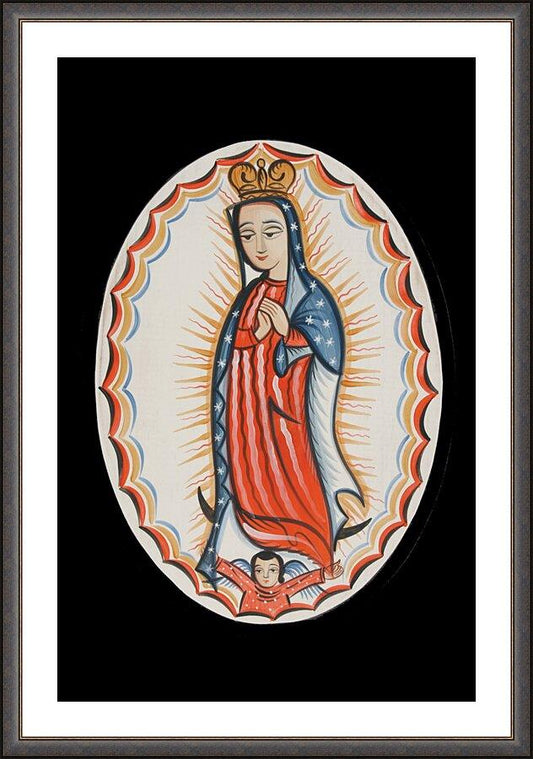

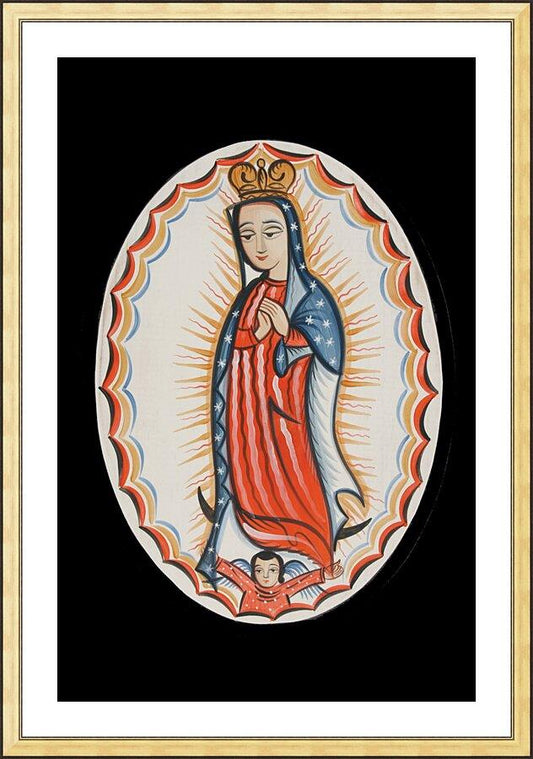

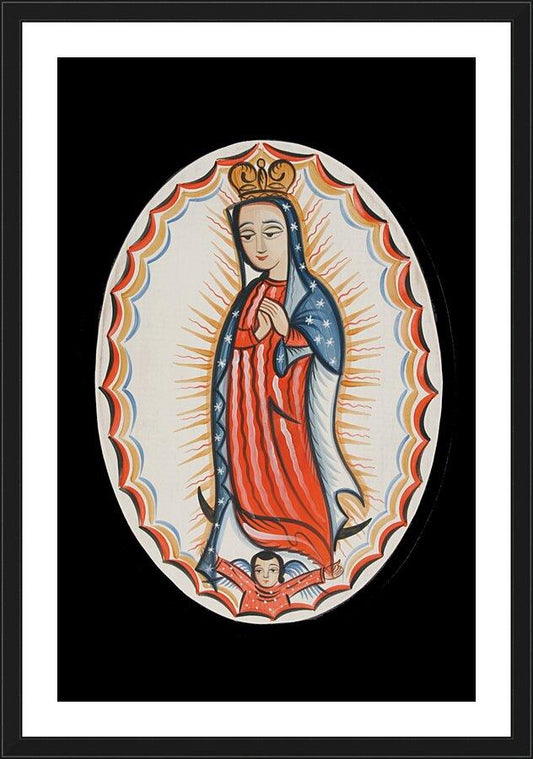

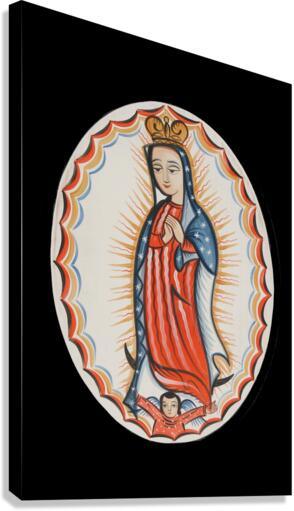

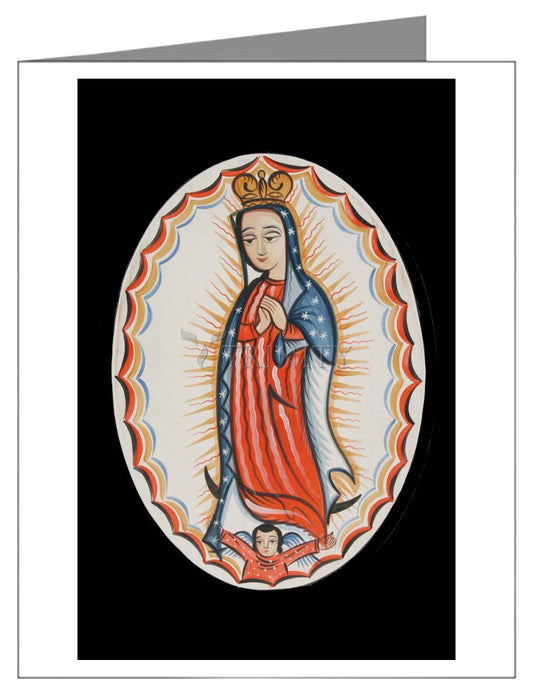

When he met with Zumarraga, Juan offered the sign to the bishop. As he unfolded his cloak the roses, fresh and wet with dew, fell out. Juan was startled to see the bishop and his attendants kneeling before him. The life size figure of the Virgin Mother, just as Juan had described her, was glowing on the tilma. The picture was venerated, guarded in the bishop's chapel, and soon after carried in procession to the preliminary shrine. The coarsely woven material of the tilme which bears the picture is as thin and open as poor sacking. It is made of vegetable fibre, probably maguey. It consists of two strips, about seventy inches long by eighteen wide, held together by weak stitching. The seam is visible up the middle of the figure, turning aside from the face. Painters have not understood the laying on of the colors. They have deposed that the "canvas" was not only unfit but unprepared, and they have marvelled at apparent oil, water, distemper, etc. coloring in the same figure. They are left in equal admiration by the flower-like tints and the abundant gold. They and other artists find the proportions perfect for a maiden of fifteen. The figure and the attitude are of one advancing. There is flight and rest in the eager supporting angel. The chief colors are deep gold in the rays and stars, blue green in the mantle, and rose in the flowered tunic. Sworn evidence was given at various commissions of inquiry corroborating the traditional account of the miraculous origin and influence of the picture. Some wills connected with Juan Diego and his contemporaries were accepted as documentary evidence. Vouchers were given for the existence of Bishop Zumarraga's letter to his Franciscan brethren in Spain concerning the apparitions. His successor, Montufar, instituted a canonical inquiry, in 1556, on a sermon in which the pastors and people were abused for crowding to the new shrine.

Pope Leo XIII approved a complete historical second Nocturne, ordered the picture to be crowned in his name, and composed a poetical inscription for it. Pope Pius X permitted Mexican priests to say the Mass of Holy Mary of Guadalupe on the twelfth day of every month, and granted indulgences which may be gained in any part of the world for prayer before a copy of the picture. The place, called Guadalupe Hidalgo since 1822, is three miles northeast of Mexico City. Pilgrimages have been made to this shrine almost without interruption since 1531-32. A shrine at the foot of Tepeyac Hill served for ninety years, and still forms part of the parochial sacristy. In 1622 a rich shrine was erected, and in 1709 a newer, even richer one. There is also a parish church, a convent and church for Capuchin nuns, a well chapel, and a hill chapel all constructed in the 18th century.

In about 1750 the shrine got the title of collegiate, a canonry and choir service being established. It was aggregated to St. John Lateran in 1754. In 1904 it was created a basilica, with the presiding ecclesiastic being called abbot. The shrine has been renovated in Byzantine style which presents an illustration of Guadalupan history.