Our Lady of Guadalupe December 12 (USA) When we reflect on the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe we learn two important lessons, one of faith and one of understanding.

Missionaries who first came to Mexico with the conquistadors had little success in the beginning. After nearly a generation, only a few hundred Native Mexicans had converted to the Christian faith. Whether they simply did not understand what the missionaries had to offer or whether they resented these people who made them slaves, Christianity was not popular among the native people.

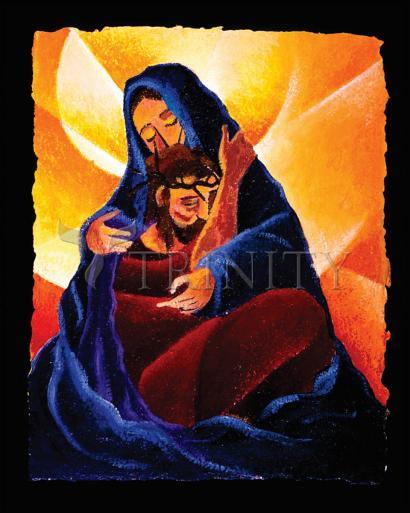

Then in 1531 miracles began to happen. Jesus' own mother appeared to humble Juan Diego. The signs -- of the roses, of the uncle miraculously cured of a deadly illness, and especially of her beautiful image on Juan's mantle -- convinced the people there was something to be considered in Christianity. Within a short time, six million Native Mexicans had themselves baptized as Christians.

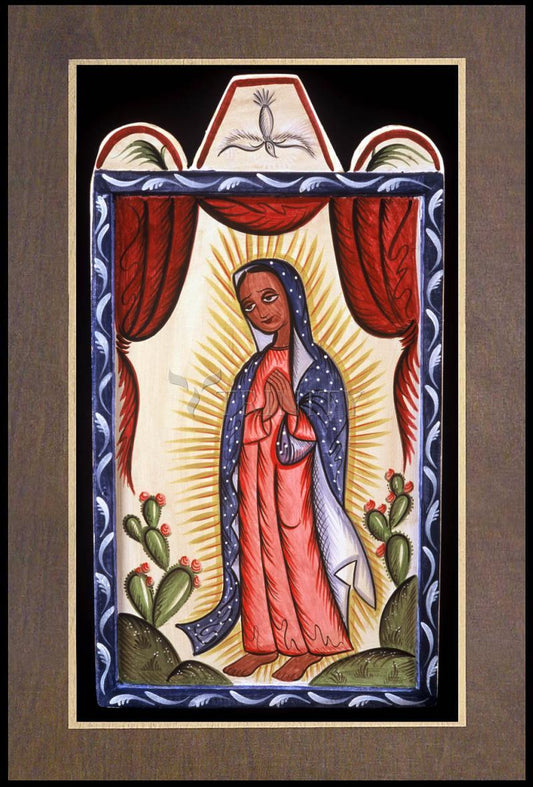

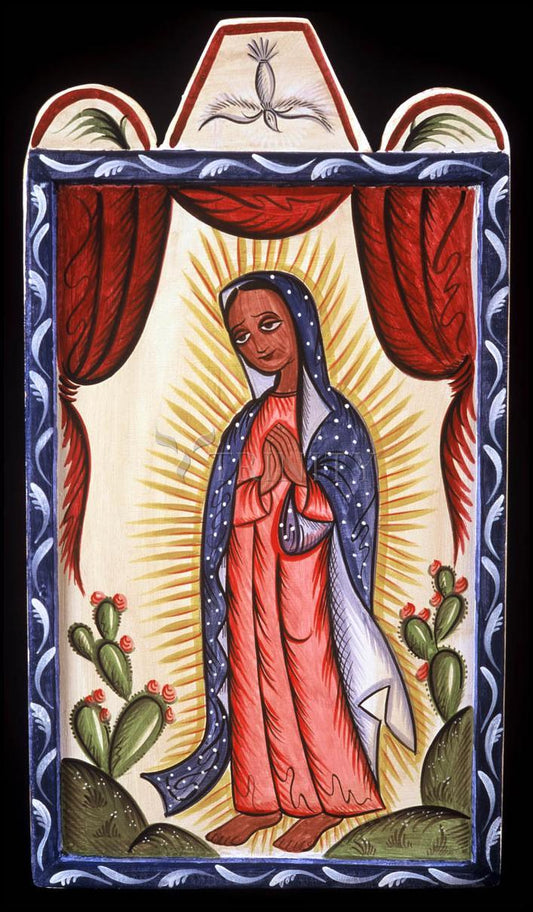

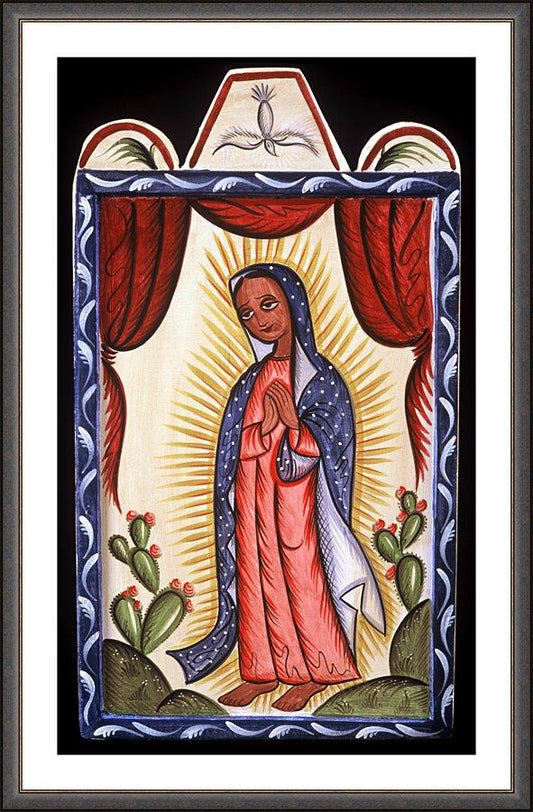

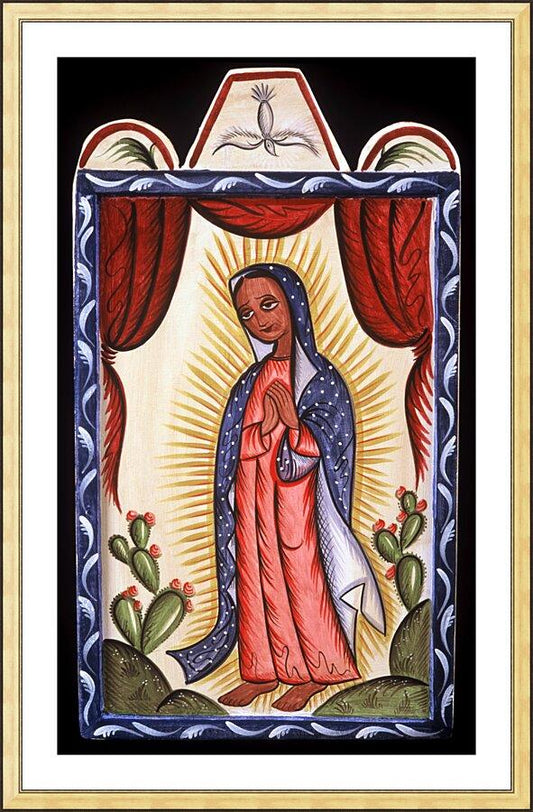

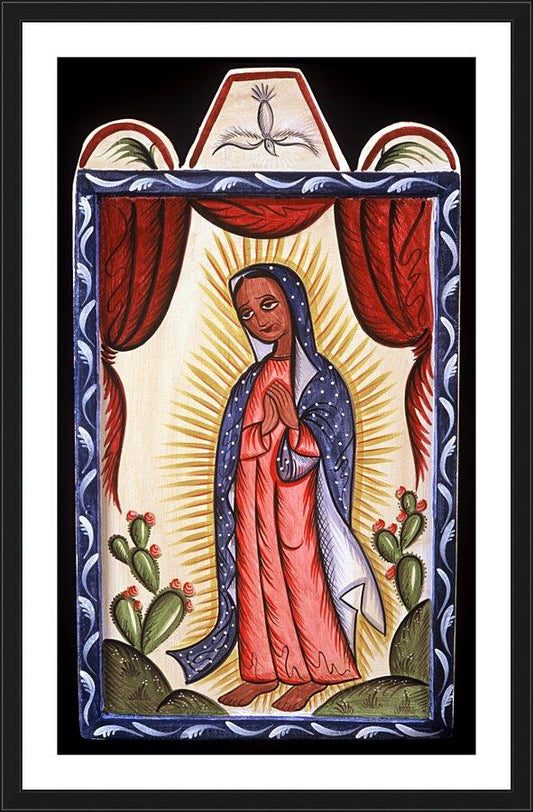

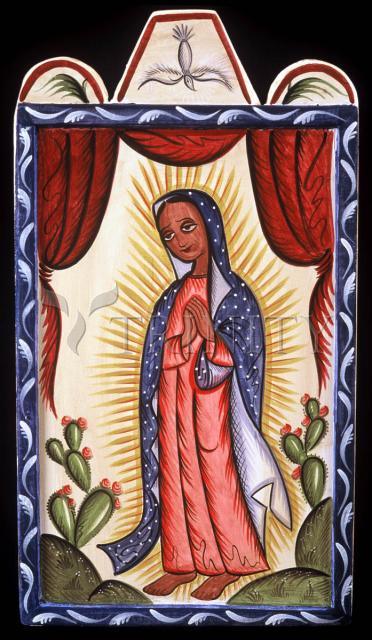

The first lesson is that God has chosen Mary to lead us to Jesus. No matter what critics may say of the devotion of Mexicans (and Mexican descendants) to Our Lady of Guadalupe, they owe their Christianity to her influence. If it were not for her, they would not know her son, and so they are eternally grateful. The second lesson we take from Mary herself. Mary appeared to Juan Diego not as a European madonna but as a beautiful Aztec princess speaking to him in his own Aztec language. If we want to help someone appreciate the gospel we bring, we must appreciate the culture and the mentality in which they live their lives. By understanding them, we can help them to understand and know Christ. Our Lady of Guadalupe is patron of the Americas.

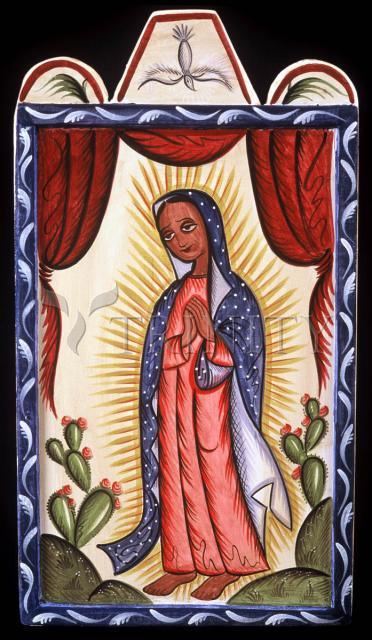

Our Lady of Guadalupe Mother Of God (Spanish: Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe), also known as the Virgin of Guadalupe (Spanish: Virgen de Guadalupe), is a title of the Virgin Mary associated with a celebrated pictorial image housed in the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in México City. The basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe is the most visited Catholic site in the world, and the third-most visited sacred site in the world.

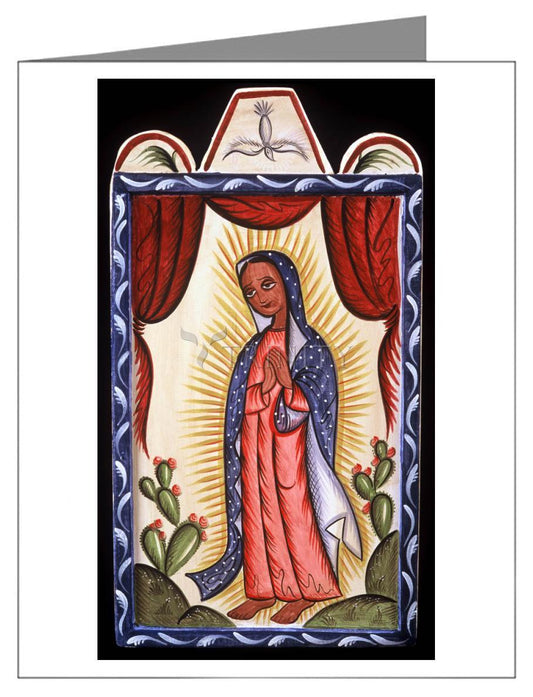

Official Catholic accounts state that on the morning of December 9, 1531, a native American peasant named Juan Diego saw a vision of a maiden at a place called the Hill of Tepeyac, which would become part of Villa de Guadalupe, a suburb of Mexico City. Speaking to him in his native Nahuatl language (the language of the Aztec empire), the maiden asked that a church be built at that site in her honor. From her words, Juan Diego recognized the maiden as the Virgin Mary. He then sought out the archbishop of Mexico City, Fray Juan de Zumárraga, to tell him what had happened. The archbishop instructed him to return to Tepeyac Hill, and ask the lady for a miraculous sign to prove her identity. The first sign she gave was the healing of Juan's uncle. The Virgin also told Juan to gather flowers from the top of Tepeyac Hill, which was normally barren, especially in December. But Juan followed her instructions and he found Castilian roses, not native to Mexico, blooming there. The Virgin arranged the flowers in his tilma or cloak, and when Juan Diego opened his cloak before archbishop Zumárraga on December 12, the flowers fell to the floor, and on the fabric was the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe.

Juan Diego's tilma has become Mexico's most popular religious and cultural symbol, and has received widespread ecclesiastical and popular support. In the 19th century it became the rallying call of American-born Spaniards in New Spain, who saw the story of the apparition as legitimizing their own Mexican origin and infusing it with an almost messianic sense of mission and identity - thus also legitimizing their armed rebellion against Spain.

Nevertheless, many Mexican clergymen have historically opposed the devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe (see below). Even recently some Catholic scholars, including the former curator of the basilica, Monsignor Guillermo Schulemburg, have openly doubted the historical existence of Juan Diego. Schulemburg said in an interview that Juan Diego was "a symbol, not a reality", and that his canonization would be the "recognition of a cult. It is not recognition of the physical, real existence of a person." Nonetheless, Juan Diego was canonized in 2002, under the name Saint Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin.