The Martyrs of Gorcum:

Today, when many Catholics seem to regard the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist as inconsequential (they wouldn't mind if the bread were just bread, really), and when many seem to regard the Pope's headship of the universal Church as a kind of embarrassing error (they wouldn't mind if the Pontiff were just a Chairperson, really) - at such a moment it may be good for us to recall the careers of a group of Catholics who realized, when asked to disavow the Eucharist and the papacy, that they minded very much. They minded so much that the threat of death - and the promise of life, if they would acquiesce could not move them.

They were 19 priests and brothers suddenly put to the test one day when their routine was shattered by an unexpected act of war, and they are known as the Martyrs of Gorcum. Gorcum was a little town on the seacoast of Holland, and one June day in 1572 it became the scene of a religious drama with mortal consequences. Holland, like all of Europe at the time, was fragmented religiously and disordered politically; under the rule of Spain, Holland was restively seeking national independence. Europe was in the throes of Reformation and Counter-Reformation, and even a peaceful village of farmers and fishermen such as Gorcum might be touched by these wider currents. Gorcum had a couple of Catholic parishes and a Franciscan friary, but the next town, Briel, was largely Calvinist.

On June 26, 1572, a kind of private armed force under the Baron de la Marque sailed into Gorcum and took over the town. Called the Watergeuzen (the Sea Beggars), they were, frankly, pirates, but they were also staunch Calvinists whose anti-Spanish politics meshed comfortably with their anti-Catholic theology. These freebooters were convinced that Catholicism had to be wiped out, and they began rounding up all the priests and brothers they could find.

We know the names of these sudden prisoners: Fr. Leonard Vechel, pastor of Gorcum, and his curates, Fr. Nicholas Jannsen and Fr. Godfrey van Dunyan. The guardian of the Franciscan friary, Fr. Nicholas Pieck, was captured, and his priests with him: Fr. Jerome van Weerden, Fr. Anthony van Hoornaer, Fr. Anthony van Weert, Fr. Theodore van der Ems, Fr. Godfrey van Mervel, Fr. Nicasius Jannsen, and Fr. Anthony van Willehad, who was about ninety years old. With them were two lay brothers, Cornelius van Wyk and Peter van Assche. Also captured were an elderly Augustinian canon, Fr. John Oosterwyk, and two Norbertine priests, Fr. Adrian van Hilvarenbeek and Fr. James Lacops (a problem religious, rebellious, defiant of authority, and most unobservant of his religious duties). There was also a Dominican father, John van Hoornaer, who when he heard of the trouble came to aid his brethren. He was seized after conducting a clandestine baptism in the woods.

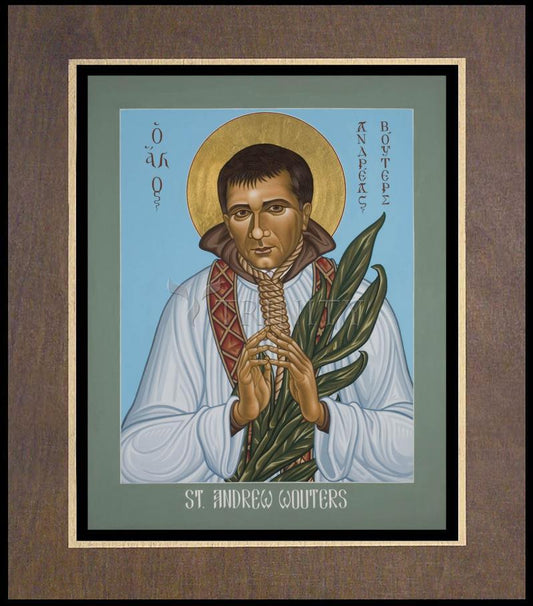

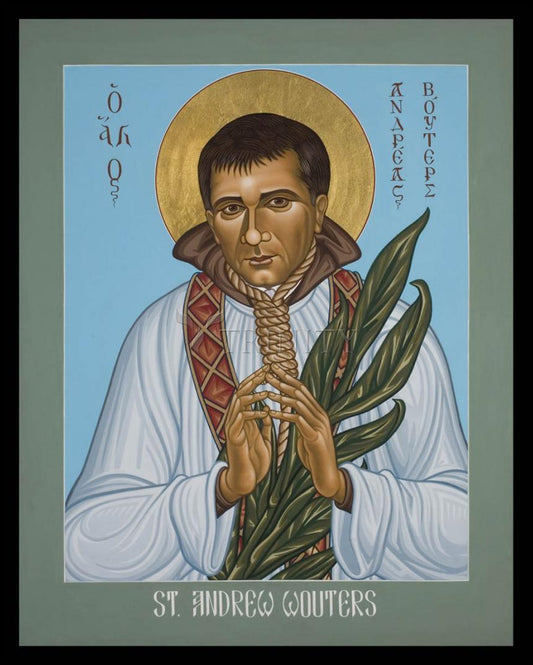

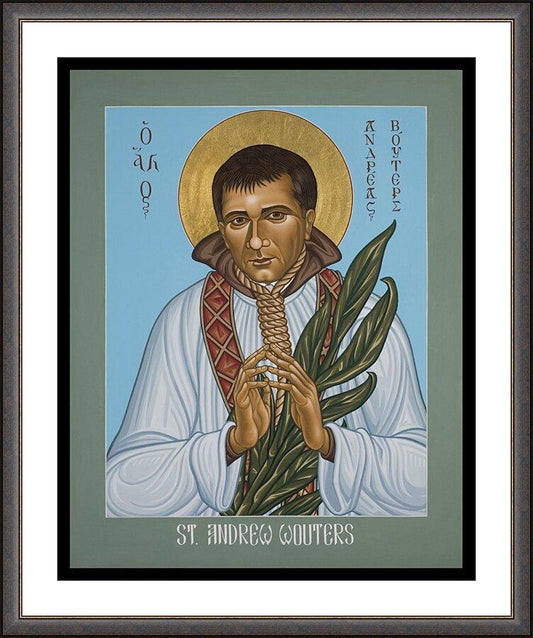

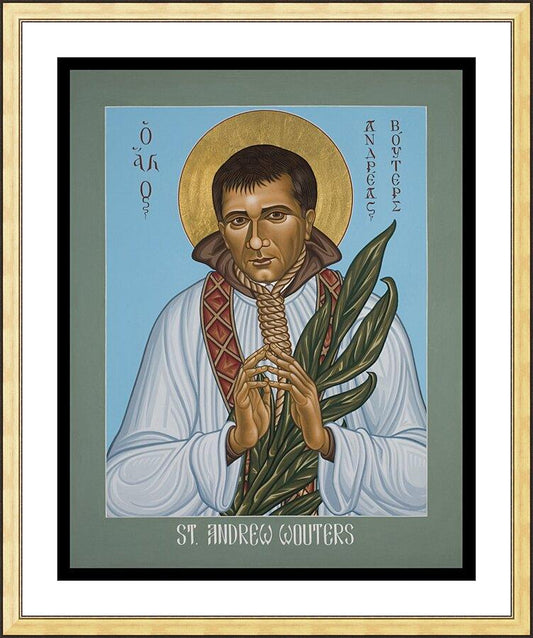

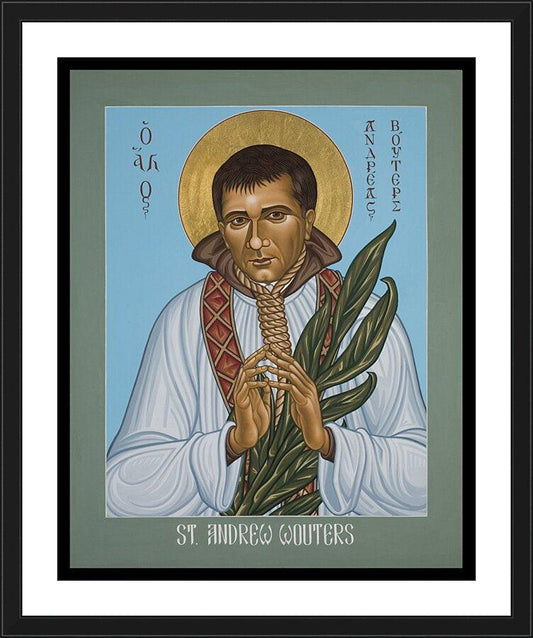

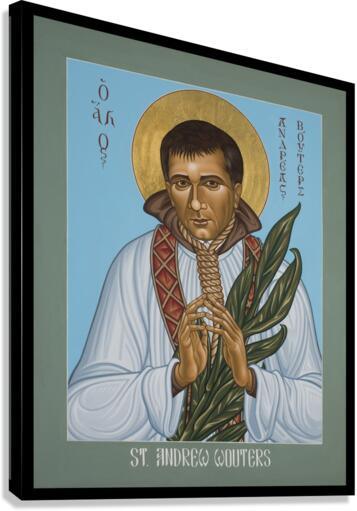

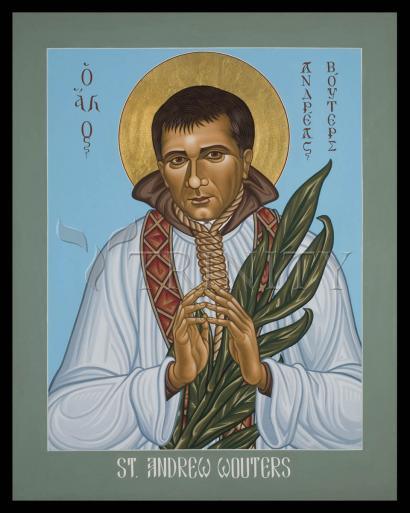

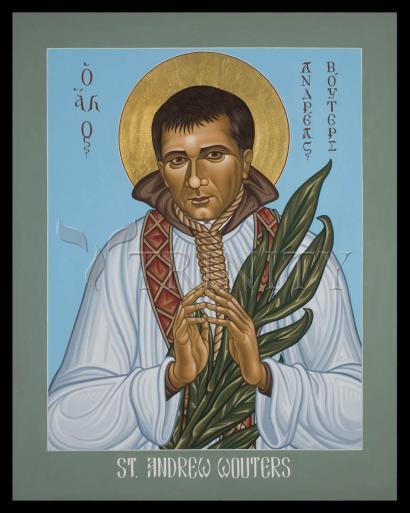

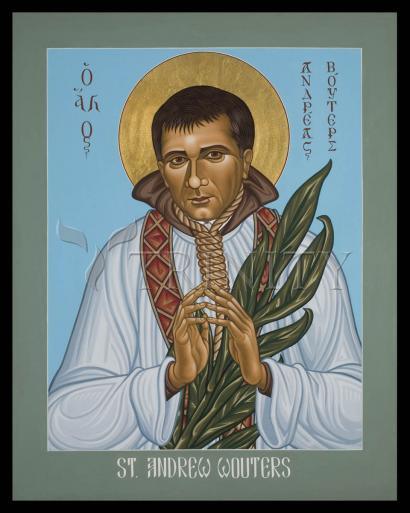

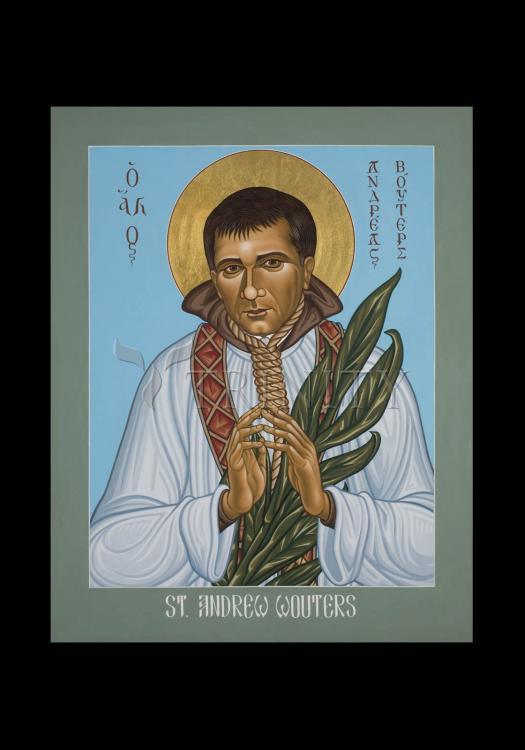

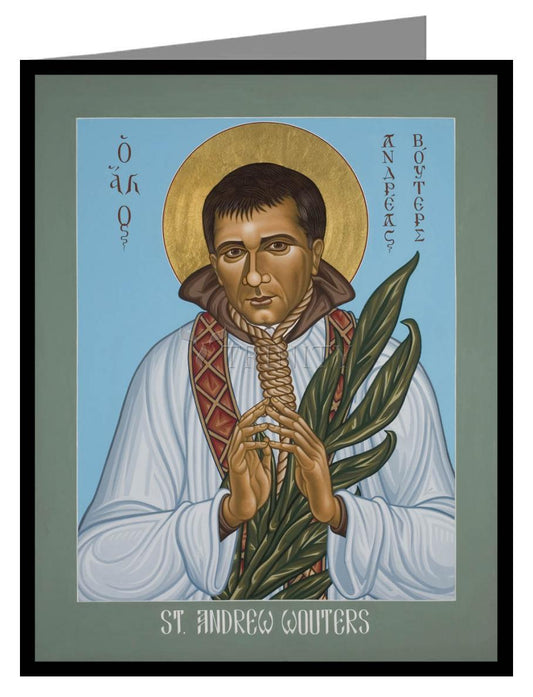

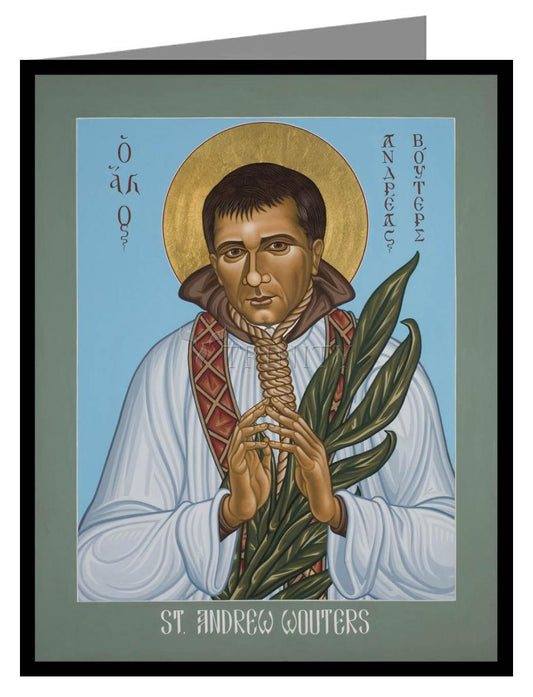

To this group of prisoners for the faith was added perhaps the most unlikely saint to win Heaven since Dismas the Good Thief. Fr. Andrew Wouters was a diocesan priest who had not been rounded up but voluntarily joined his priestly confreres in captivity. Fr. Wouters had not been faithful to his promise of chastity and had led a scandalous life that was notorious all over the parish and beyond. Not previously a very spiritual man, he nonetheless showed himself a man of spirit by taking his place among the prisoners. When his past failures were thrown in his face by his captors as a disgrace to his calling and a negation of his creed, he looked them in the eye and said, "Fornicator I always was, heretic I never was."

The commander of the Sea Beggars had the prisoners taken by boat to Briel where they were mocked by being forced to process around the town square singing the Litany of the Saints. Calvinist ministers were brought in to interrogate the Catholic clergymen so that they could be harangued with the "new discoveries" of Calvinist theology. The ministers zeroed in on the Catholic belief in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. They utterly denied it, declaring that Communion is only a memorial meal, and that it is not necessary to have priests ordained by bishops standing in the Apostolic succession in order to have a Eucharist. The prisoners in response would not deny one iota of the Catholic Church's doctrine on the Blessed Sacrament.

By now the people and magistrates of Gorcum were clamoring for the return of their priests. The Calvinist admiral was flooded with letters and appeals to spare the lives of the captive clergymen, among them an order from the Prince of Orange not to execute them and a plea from Fr. Pieck's two brothers to spare his life. At this the pirate-admiral proclaimed that they could all go free if they would publicly state that the pope is in no way the head of the church. The Gorcum priests and their companions adamantly refused to do so. They stood their ground courageously.

The admiral ignored every plea, and martyrdom came swiftly. Just after midnight on July 9, 1572, the admiral sent an apostate priest who had quit his priesthood to bring the prisoners to their place of execution on the outskirts of Briel. When they arrived at what was left of a former monastery, they were taken to a turf shed. Here the apostate priest helped to hang them from the roof beams. By dawn every one of them was dead. Fidelity to their faith and their allegiance to the Holy Father had cost these men the ultimate price.

They were cut down and their bodies dumped into an inglorious grave where they remained, unhonored, for over forty years. During a truce between Spain and Holland, permission was granted to exhume the bodies and to bring the sacred remains to Brussels, where they were enshrined in a Franciscan church. Pope Pius IX declared these loyal supporters of the papacy and Magisterium to be saints in 1867.

The priests and brothers of Gorcum dangled from the roof beams for their faith in the Real Presence and the authority of the pope. Their belief in the Eucharist and the papacy echoed the belief of Peter in Jesus, the trust of the fisherman (who was to become the first pope) in the Savior Who was to institute the Eucharist. In the sixth chapter of St. John's Gospel, when Jesus said that His followers must eat His flesh and drink His blood, many turned away. When Jesus asked Peter if he too would turn away, Peter said, "To whom shall we go, Lord? Thou hast the words of eternal-life."

"Excerpts from "The Martyrs of Gorcum", The Rev. Barry Bossa, S.A.C.