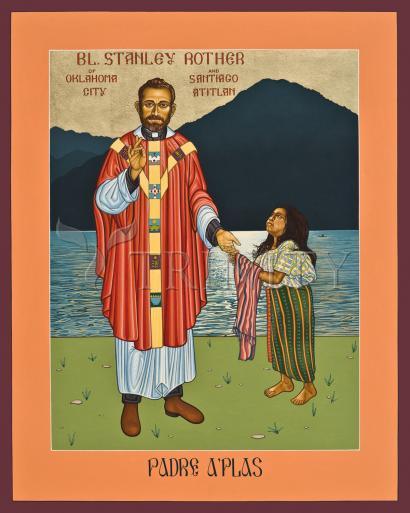

Collection: Bl. Stanley Rother

-

Sale

Wood Plaque Premium

Regular price From $99.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$111.06 USDSale price From $99.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wood Plaque

Regular price From $34.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$38.83 USDSale price From $34.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wall Frame Espresso

Regular price From $109.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$122.17 USDSale price From $109.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wall Frame Gold

Regular price From $109.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$122.17 USDSale price From $109.95 USDSale -

Sale

Wall Frame Black

Regular price From $109.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$122.17 USDSale price From $109.95 USDSale -

Sale

Canvas Print

Regular price From $84.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$94.39 USDSale price From $84.95 USDSale -

Sale

Metal Print

Regular price From $94.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$105.50 USDSale price From $94.95 USDSale -

Sale

Acrylic Print

Regular price From $94.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$105.50 USDSale price From $94.95 USDSale -

Sale

Giclée Print

Regular price From $19.95 USDRegular priceUnit price per$22.17 USDSale price From $19.95 USDSale -

Custom Text Note Card

Regular price From $300.00 USDRegular priceUnit price per$333.33 USDSale price From $300.00 USDSale

ARTIST: Lewis Williams, OFS

ARTWORK NARRATIVE:

Padre A’plas (Father Francis), the name given him by the Tzutuhil Mayan Indians, was an unassuming farm boy from Oklahoma who found learning Latin difficult. Forced to repeat a year in seminary, he was later asked to leave. A new seminary and tutoring in Latin led to his ordination in 1963. In 1968, he joined Micatokla (Catholic Mission of Oklahoma) in Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala, and found his life’s work, even mastering the Tzutuhil language. War eventually came to these gentle, poor people and their beautiful mountains and lakes. A right-wing military dictatorship fought leftist Guerillas over redistribution of land and wealth. Death squads kidnapped, tortured and killed those the government felt were a threat. People were ‘disappeared’: many in his parish.

Witnessing the kidnap of one of his catechists, Diego Quic, and finding himself high on the death list, he returned home. Guest speaking at an Oklahoma parish, he voiced sentiments challenging our governmental policies related to the escalating violence in Guatemala. Two parishioners questioned his patriotism. One wrote the Guatemalan embassy regarding him. His fate was being sealed. Guatemala priests were being killed. Stating that a shepherd can’t abandon his flock, he returned. On the night of July 28, 1981 a few days after the town’s biggest festival celebrated with First Communions and Marriages, he was asleep in a first floor room. Three tall men broke in, and with threats found their way to his room. Fr. Stan fought them, adamant they would not take him to be tortured and killed elsewhere. “Kill me here!” he yelled. Firing two shots into his head, he died with and for the people he was blessed to serve for 13 years. His heart and blood remain with his people; his body rests at home, close to his family. This beloved martyr’s cause is being lifted for canonization.

b. March 27, 1935 – d. July 28, 1981.

- Art Collection:

-

Martyrs & Holy People

- Williams collection:

-

Martyrs and Holy People

Father Stanley Rother was murdered by three masked men in the rectory of his church on the night of July 28, 1981. He was 46 years old, a missionary serving the Tzutuhil Mayan Indians in Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala, for thirteen years. At the height of a 36-year long civil war, Stan Rother, a quiet farm kid from Okarche, became Oklahoma's only martyr.

The path to such spiritual heights wasn't assured. He possessed physical strength from a lifetime of farm chores, and was gifted with mechanical know how, but he struggled in the seminary. Latin was a particular problem, making it difficult to wade through textbooks written in the language of the church at that time. He failed to pass critical classes at Assumption Seminary in San Antonio, and was asked to repeat a year, then to leave. No one would have written in his yearbook "most likely to become a saint."

Back home, a bishop and others who believed in his potential intervened, and the young man stayed on the path to the priesthood. He was tutored in Latin in Oklahoma, and the following year transferred to Mount Saint Mary's Seminary in Emmitsburg, Maryland. There he encountered no further problems, and was ordained in 1963. He began his career as a parish priest in local churches.

Five years later he volunteered to join Micatokla, or the Catholic Mission of Oklahoma; a team of young, energetic priests, nuns, and volunteers sent in agreement with the local diocese in Guatemala. The American missionary group was brimming with the energy and idealism of the early 60's. Father Paul Gallatin, Pastor of St. Charles Borromeo remembered, "They had started a number of projects, and probably hoped Stan would be the one to keep the generators running. He was needed there because no one could fix anything."

When he encountered him years later, Father Gallatin's initial impressions of Father Stan deepened. He said, "This was a man who had grown immeasurably. He knew who he was and where he fit."

And speaking of languages, by his own account, Father Rother arrived at his post knowing about ten words of Spanish and no Tzutuhil. Eventually he became so immersed in both he could preach and converse, and his mother noticed his English tinged with a slight accent.

The Micatokla group served the Tzutuhils, an indigenous people rich in an ancient heritage, but suffering some of the highest poverty rates in Central America. Without resident clergy for over 100 years, their ancient beliefs steeped into a unique mixture of Mayan ritual and Catholic tradition. For the traditionalists, saints and gods with slippery identities were prayed to with offerings of maize, incense, and candles.

For twelve years, from 1968 to 1980, Padre A'plas--his Tzutuhil name--overcame challenges--from learning languages, adapting to a strange religious mix, farming in a semi-tropical mountain climate, building a hospital, training catechists, or volunteer religion teachers, restoring the church building, forging friendships, offering Masses at

the church, and then traveling rough roads to do the same in chapels at outlying fincas, or plantations.

Those paled in comparison when la violencia--the violence--arrived in the beautiful Lake Atitlan area. Santiago Atitlan was one of the hardest hit. By war's end, several hundred residents died.

In a letter Father Stan wrote, "The low wages that are paid, the very few who are excessively rich, the bad distribution of land--these are some of the reasons for widespread discontent."

The players in the war were a right-wing military dictatorship versus leftist guerillas fighting for overthrow of the government, and redistribution of land and wealth. In between was a majority Indian population in Santiago Atitlan, wanting to live in peace, but instead, the war's most numerous victims.

In 1980 both sides clashed in the Lake Atitlan area. Shortly thereafter, 11 villagers became "the disappeared." The random kidnappings, torture, and murders of civilians by death squads scared the people into silence. Guilt by association, whether real or imagined, became a reason for being picked up for questioning. Many never returned.

By this time, Padre A'plas had been pastor of St. James the Apostle Church for five years, the last one left of the American group. The villagers looked to him for help. It was the Padre who smuggled letters via friends, asking aid for 8 widows and 32 orphans. It was the Padre who let the church be a sanctuary for people too terrified to sleep in their own homes. It was the Padre who asked military brass at a town meeting why there had been no disappearances before the army's presence. He took the silence out of their fear, but these "crimes" made him a target.

Shortly after witnessing the kidnapping of a catechist, Padre A'plas learned he was number 8 and the associate pastor number 9 on a death list. The threat was real enough to send both to safety in Oklahoma in January 1981.

Despite warnings not to go back, Padre A'plas returned alone to Santiago Atitlan three months later, just before Holy Week. Semana Santa, one of the most important events of the year, marks the Resurrection, the start of the rainy season, and the crop growing cycle in elaborate Catholic and Mayan rituals and processions. He could not leave this duty to someone else. Nor could he forsake the people he considered his family at their worst crisis. He said, "I have too much of my life invested here to run."

In his 1980-81 letters home Father Rother often closed with, "Say an extra prayer for our safety." He assured friends and family he had an escape plan. He also mentioned it was likely he would receive another direct threat, giving him time to get away.

If not, he was prepared. Should someone come for him, he let a few folks know that they would never drag him out of the house. He feared torture more than death.

Padre A'plas died four months after returning to Santiago Atitlan . The three tall men who broke into the rectory after midnight could not overpower him. They beat him and shot him twice.

To this day, his murder remains unsolved, though it is widely suspected to be the work of a paramilitary death squad. "Tall" was an important clue. The attackers' height indicated they were not Tzutuhils, who average 5'5" or less.

Padre A'plas selfless acts in life and death have earned him a place on another list, among the 78 Central American martyrs who will someday be considered for sainthood. Their names were submitted to the Pope in 1996, the same year the war ended with the Guatemala Peace Accords.

The Archdiocese of Oklahoma City has declared 2006 the Year of Father Stanley Rother.

He was an ordinary man facing extraordinary circumstances. He was underestimated by some, and appreciated by many. His humble service and ultimate sacrifice can inspire the rest of us to strive for our own best, whatever that may be. He is already considered a saint by the Tzutuhil people.